Keith Allison is busy discovering the truth about aliens and so recommends this week you enjoy his piece on John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy.

~~~

I read, not so very long ago, an article intent on wringing its hands over just how dark and bleak and apocalypse-obsessed modern young adult fiction tends to be. It’s all full of kids getting oppressed, leading uprisings, getting hunted down for sport, surviving the destruction of the earth and trying to make a new life. And while there may be a certain bleakness to be sure, I was wondering if the author of this article had ever read any previous generations of young adult fiction. I mean, I grew up in a time when “child must kill a beloved pet” was a whole genre, and while that may not be apocalyptic, you can’t tell me Old Yeller isn’t substantially more devastating and dark than the destruction of the world.

Young adult fiction, in all its iterations from Robinson Crusoe to The Hunger Games, often explores dangerous, tense, and sometimes downright horrifying scenarios. And it’s no surprise that these tales, whether they are adventure or post-apocalypse, appeal to kids while puzzling the adults who forgot how to appreciate such stories. Their sense of adventure appeals to a yearning for freedom at a time when children are straining under the yoke of parental and academic rules. Their forays into apocalypse speak to the feeling that something is wrong with the world, that the older generation has done a terrible job, and that struggling to survive in a ravaged aftermath is preferable to doing what aged and corrupt politicians command.

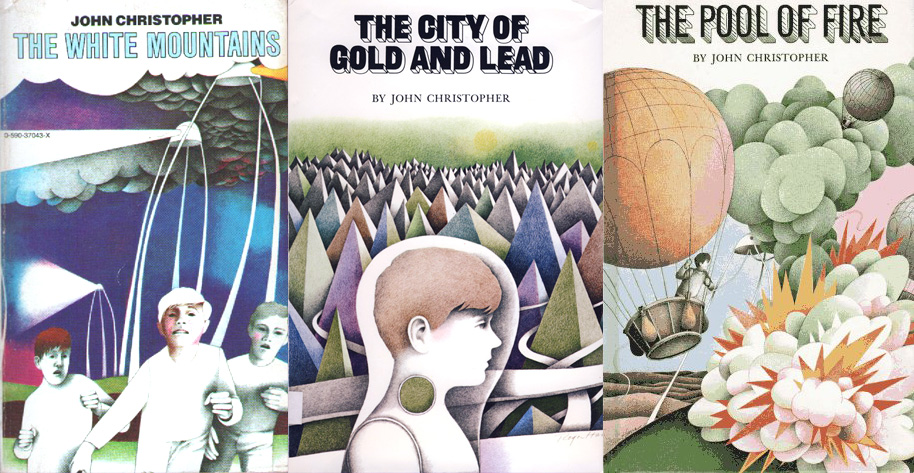

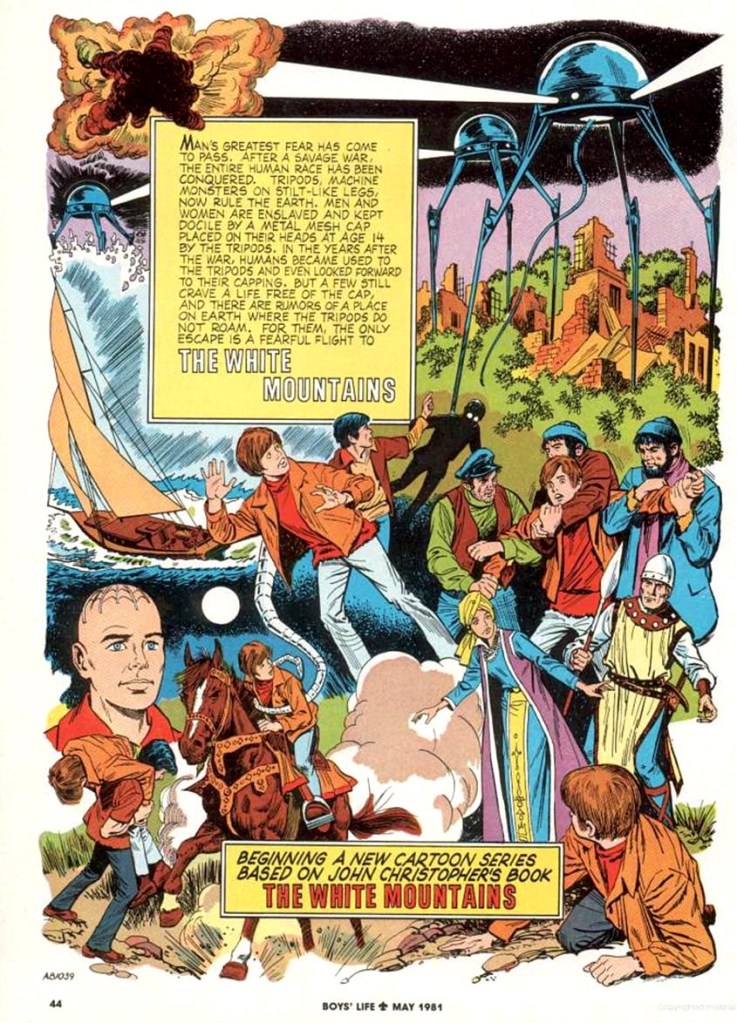

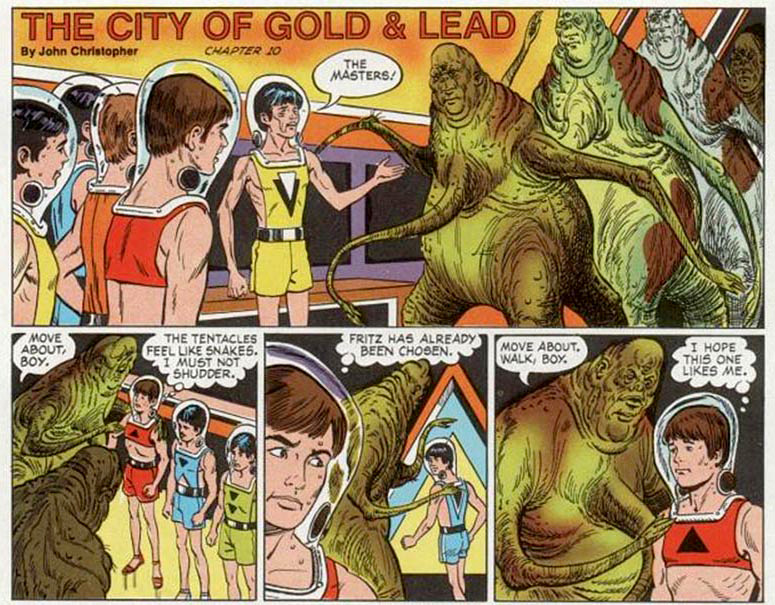

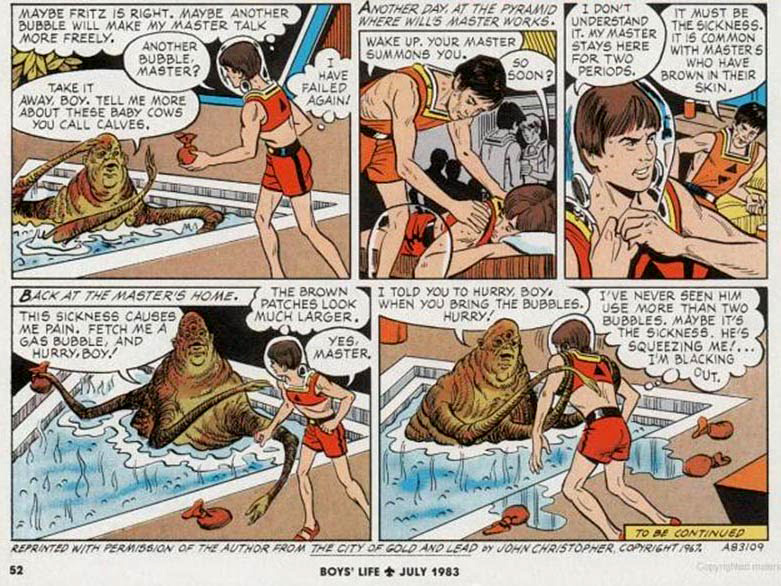

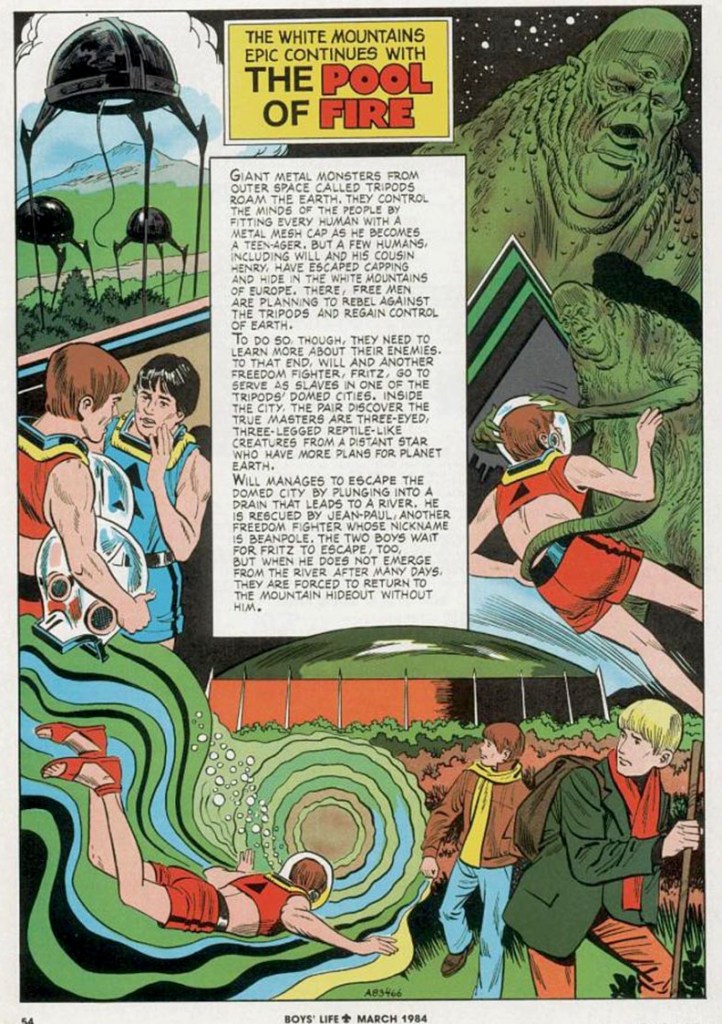

I was, in my day, particularly fond of John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy, which combined “boy’s own adventure” with post-apocalyptic science fiction. I first ran across it when it was serialized as a one-page comic strip in Boys’ Life magazine, which as a Scout and a kid growing up surrounded by woods in the rural Kentucky of the 1970s, I read without fail. Never know when you’ll need to now how to splint a fracture, wax a car, or stitch together a wineskin. The White Mountains‘ bizarre combination of sci-fi gloom, a quasi-medieval world, friends on a trek, and a rising up against oppressive overlords snared my attention immediately. I sought out the books themselves — The White Mountains, The City of Gold and Lead, and The Pool of Fire — as soon as opportunity allowed and plowed through them in a matter of a few days. Recently, I returned to them to see how they’d aged, or how I hadn’t.

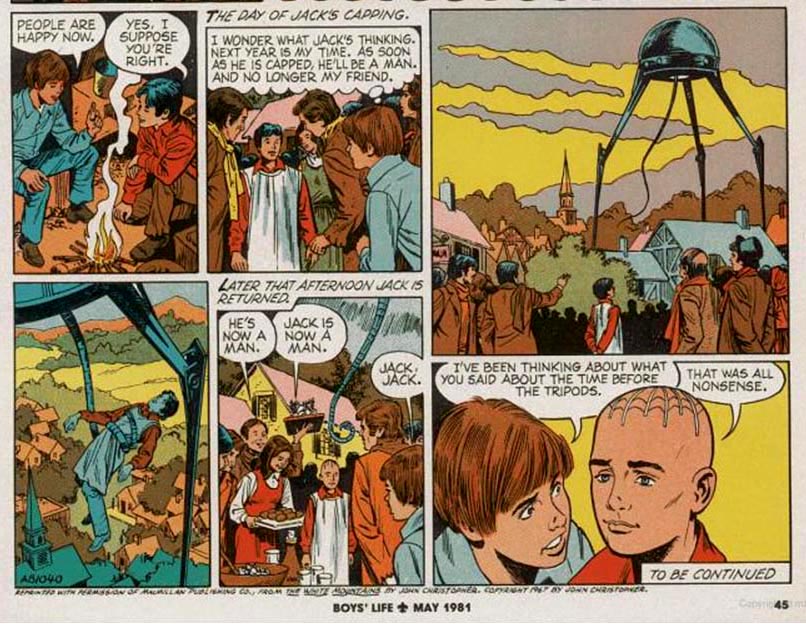

Set in a not-so-far-flung future, the first of the books sets up the world inhabited by young Will. It is an agrarian society, returned to the feudal system in many regards, but with the decaying and mysterious remnants of 20th century man strewn across the world. Lording over all are the tripods, mysterious, towering creatures that control the will of humans by “capping” them with a spidery mesh affixed to the scalp on their 14th birthday. Capping is much looked forward to by the human subjects and celebrated with a day of feasting and revelry. But Will, upon noticing the change from “clever and energetic compatriate” to “distant and disinterested stranger” that occurs in his cousin, begins to question the desirability of being capped.

Will encounters a vagrant — someone for whom capping didn’t quite succeed, turning them into mad wanderers — and soon discovers the man isn’t a vagrant; he’s never been capped and is, in fact, a representative from an enclave of free and uncapped people far to the south in what he calls the White Mountains. When Will’s time to be capped comes around, he decides to rebel, to set off on foot in search of the free thinking men and women of the White Mountains. Joining him on his quest is a hated cousin, Henry, himself due for capping and a surprising ally since the boys hate one another and have never talked about a shared fear of capping (in fact, no one talks about capping, except to celebrate it).

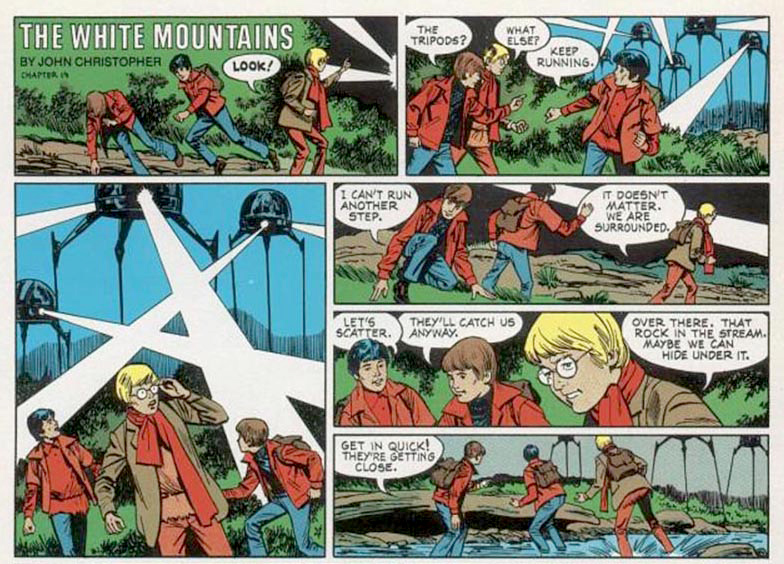

So begins a sprawling trek across England and France 9and in later books Germany, Central America, and Central Asia), where they pick up a third companion, Jean-Paul, who they dub Beanpole. They pass through the crumbling remains of the great cities of the 20th century, full of forgotten and inexplicable wonders, are pursued for much of the way by the menacing Tripods that behave in curious ways. At times they seem merely curious, while at other times are obviously bent of capturing or killing the young fugitives. In the subsequent two books of the series, the three lads, along with a fourth named Fritz, will discover the Masters of the Tripods, deal with drunken barge captains, enter the hellish city of the Masters as spies, and eventually take part in an armed insurrection against the Masters and the horrible fate they have in store for Earth.

Christopher’s ability to involve us in the young protagonists makes everything all the more effective. The chapters of The White Mountains in which Will, Henry, and Beanpole explore the ruins of a vast city (presumably Paris) and try to puzzle out the weird things they see is fantastic. And the descriptions of the lives of Will and Fritz amid the content and wasted slaves in The City of Gold and Lead is alien, oppressive, and evocative. One can feel every ounce of pressure from the artificial gravity, every drop of sweat from the domed city’s tropical heat. And the Masters, when they are revealed, are not just some vaguely humanoid and comprehensible creatures. they are thoroughly alien, and not entirely and uniformly evil as Will had hoped. The creeping doubt, the potential “disappointment of victory,” looms over the revolution in The Pool of Fire with its downbeat upbeat ending. And hey! This is a series for kids where one of humanity’s greatest weapons ends up being our booze distilling experience!

What really struck me upon rereading the trilogy (there is a prequel, written years after the fact, that is best ignored), is how complex a portrait it paints of this future where men are controlled by machines. For the most part, there is little in the way of overt oppression. Human society, having been wiped out and rebuilt by the tripods, is allowed to proceed more or less as it wants. There is no war, and little in the way of disease. Men and women marry, have children, work the fields, sail the seas, get drunk in taverns and have brawls. By and large, they are happy, as cattle seem happy. And the free humans are not the picture of infallible can-do virtue. They squabble, and they have no idea what to do if they win — a prospect that seems unlikely. In fact, it seems likely that a human victory will almost certainly result in the return of war, famine, disease, and crime. Living as we do in a society that is increasingly insistent on monitoring every aspect of its citizens’ lives — for their own good — Christopher’s Tripods trilogy remains depressingly relevant. How much is freedom worth, and what are willing to sacrifice in pursuit of safety?

It is only as Will, Henry, Beanpole, and Fritz continue to delve deeper and deeper into the society of the Masters that we see the nasty underbelly of the utopia that has been created for compliant man. The slavery that occurs in the city, the manipulation of human will to make slavery the most desirous of stations in life, and ultimately, the master plan of the Masters. Even then, the books do not let their (presumably young) readers off the hook. This is not a story that ends with human triumph and the assumption that everything is great now that we are free. The complexity of what happens when a human race united by servitude and mentally manipulated into peaceful coexistence suddenly find themselves free.

Similarly complex is the protagonist of the story, Will. He is a likable, complex, flawed character, not the best or brightest of the small gang that makes their way across this strange future landscape. Henry is braver; Beanpole is smarter; and Fritz is more tempered. Will is hot-headed, sometimes jealous, and often make bad decisions (and is often outvoted by his companions, for the better). When he, Henry, and Beanpole stop for a respite in a castle and Will meets a kind, beautiful young woman and her welcoming parents, he seriously second-guesses his opposition to capping. He is an easy character to identify with, because he showcases all of the flaws and doubts that are present in most any reader. He is the person who thinks himself the hero, when in fact he is often scared and only succeeds because of luck or the wiser action of his friends. Which is one of the central points of the trilogy, that going it alone and rejecting the opinions of others, that thinking yourself always correct and infallible, will get you killed.

Neither is this a “only the young can save us” book, or one in which the main character hoards all the glory. In fact, Will never becomes a leader. He never delivers the final triumphant blow in any of their many conflicts. Beanpole, Henry, and Fritz are all considerably more successful and vital to the cause. The adult leaders of the White Mountains enclave are as important to the scheme as the young heroes. Will has some successes — most of them accidental — but though he is the main character, this is only partially his story, and it’s not a story of “the most unlikely of the group becomes the hero.” Will might be a hero, but he is a hero in the way any willing soldier is during combat. He is the sidekick, in the end, and it’s interesting to tell the story from the point of view of the sidekick.

If there is any criticism to be leveled at the series, it’s that my dubbing it a “boy’s own” adventure means it’s all about boys. With the exception of the occasional mother here and there, and the young woman with whom Will becomes infatuated, this is a story about boys having adventures for boys (which is why, despite its controversial content, it probably found its way into Boys’ Life, though to be fair, the Scouts used to be a lot more open-minded than they are these days). This boy-bias is an unfortunate but easily dismissed product of the time it was written, when it was assumed only boys liked science fiction and adventure. That’s a wrong assumption of course, and it always has been. Luckily, there’s not much about the Tripods trilogy that requires the characters to be boys. My recommendation to any girls (or women) who want to read the Tripods trilogy and see themselves in it is to take advantage of the fact that, pronouns aside, it’s a pretty gender-neutral story. It’s easy to imagine any of the four main characters as girls. Or as a different race. Or as anything you want them to be.

I found the books every bit as thrilling to read as an adult as I did as a child. Perhaps even more rewarding, as the complexities I didn’t notice in my youth (or only latched onto subconsciously) were more obvious as an adult. This was no case of nostalgia. Rose-tinted lenses were not needed. The imaginative science fiction (Christopher’s tripods may recall The War of the Worlds, but beyond that they have little in common), engrossing descriptions of alien experiences, and above all, the spirit of adventure and friendship that lives at the core of the stories keeps them from growing stale. The comic adaptations that started the obsession for me are still pretty enjoyable as well and online here, here, and here. Back issues of Boys’ Life (girls allowed) are also available via Google Books and the Internet Archive. As an uncle, I can’t wait until my nephew is old enough to read them (my sister is already way ahead of me though and has the books ready and waiting). As an adult, I am equally excited to suggest them to people my own age. The books seem hardly to have aged at all, and when reading them, neither do I.

Categories: Science-Fiction

I first came across The Tripod books when I was aged twelve in the mid-1980s and, as you can imagine, I remember being fascinated by this strange idea that when you reach the age of fourteen you had to be capped. That this must happen to boys when they finally reach their fourteenth birthdays – before they can begin to think and to reason for themselves. Indeed the Masters even considered capping all boys at the age of twelve, not only to be sure of it, but also because a younger child is less resistant and less questioning. More curious and thus more willing. In the end they decide against doing this as a child’s skull is not yet fully formed or developed. Capping Day is therefore a mandatory annual “coming-of-age” ritual for each and every boy. One in which they must all take part. Thus the head of each son and daughter is shaved before they are all assembled together to be capped. One by one. Every child is proudly presented by their parents as a new slave for The Tripods. As I child I could not understand why parents would do this. Until I realised the parents had been capped when they were children. After being presented before The Tripod, the boy is lifted up gently inside the capsule so that a cap of metal wiring can be successfully enmeshed and embedded deeply into his skull and brain. Interestingly before children are capped they often question it. “Why? I do not see why it has to happen. I would sooner stay as I am.” Indeed what teenager has not said to himself: “I will not believe in what adults believe in. I will rip up the rules of society. I will never conform like them.” Therefore as the child is taken to be capped he must be very gently reassured, encouraged and, most importantly of all, made curious by the adults as to what Capping is. “You can’t understand now, but you will understand after it happens. I can’t describe it. You won’t be hurt. As a person I am happy now.” Indeed when boys are returned to their parents, it soon becomes clear they no longer question as teenagers but are happy and contented adults. Yet another generation of future slaves successfully programmed and educated to serve, obey and even worship the current social, economic and political order. Their new Master. Their God, their Ruler, their State. Sound familiar. I recommend that parents today do encourage their children to read these subversive books. Particularly boys aged twelve.

LikeLike