Clones are pretty much always a problem. There’s rarely an unequivocally good reason for creating them, and even if there was it never works out the same way in reality as it did in theory. (Arguably it works out very well for the aliens in the 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, who appear to be on their way to successfully populating Earth with pod people, but that’s a matter of perspective). One thing most of the clone and android movies that I’ve seen have in common, though, is the central ethical question of whether they deserve to be treated like people or resources. It’s so often the main thread of the story that it was refreshing to watch Riley Stearns’ film Dual (2022), where society has clearly already made the call on that question and moved on to the point where you might end up having to fight a duel to the death with your clone to determine who gets to live out the rest of your life.

I’ve watched and read a lot of stories about androids and clones. I’ve even written articles about them from different angles, including “The Man from the Tin Can” on the bespoke android matchmaking service in Maria Schrader’s fantastic film I’m Your Man (Ich bin dien Mensch), and “What’s Wrong with Dating a Clone?” on the absurdity of the reality dating show Game of Clones where every contestant looks almost identical. More recently, clones have shifted from firmly in the realm of sci fi, like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956 and 1978), Parts: The Clonus Horror (1979), or the clone-adjacent Replicants in Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner (1982) to the world of emotional dramas in films like Benjamin Cleary’s Swann Song (2023) or Mark Romanek’s 2010 adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go, which has the quality of a slow-moving BBC period piece. As science and technology have advanced to make the reality of them seem more possible, androids and clones have started to show up as a focus in more realistic genres.

Many of the more recent clone dramas are excellent, but I am a liminal sci-fi pulp creature at heart so the disturbing off-kilterness of Riley Stearns’ Dual immediately appealed to me more. I’m not sure I can say that I enjoyed watching it exactly – honestly, it’s uncomfortable and a bit bleak even when it’s funny – but it surprised me, and it’s stuck with me and actually made me think. The main character, Sarah (Karen Gillan), is an apparently depressed woman who spends her time drinking, avoiding her mother’s many phone calls, and trying to connect with her boyfriend, who is away on business and seems disengaged. When she’s diagnosed with a terminal illness, the doctor gives her a pamphlet from The Facility about having a clone created so her family won’t have to grieve. “Replacement” is a service only available to people who are dying (or intending to commit suicide), and one of their promotional slogans is “you may be dying, but don’t let that affect the ones who love you!”

The doctor says her chances of surviving are zero and her chances of dying are 98%. After some back and forth on that math, which the doctor insists is sure thing despite a 2% margin of error, Sarah goes home and watches a cheesy infomercial for the cloning company. This is where we’d usually get some exposition to explain how this came to be the thing people do when they’re dying, but she gets bored with those parts and skips them so we never find out. She makes an appointment and gets talked into having a clone created for her on the spot, which turns out to be one of those one hour while-you-wait services. It’s very expensive, but the salesperson explains that they have an installment plan and her clone will simply take over the payments along with the rest of her life. What is actually happening here is ridiculous, but the way no one treats it like anything unusual makes it feel so much like a real life experience in every way except for what she’s buying that they could be selling her a car or a new pair of glasses. She also has a remarkable lack of affect about all of it, which I initially thought was because she’s depressed, then that she might be autistic, but it turns out to be a stylistic choice on the part of the director. It does actually make the whole thing seem much more normal than it would if she had big feelings about it.

Sarah never intends to tell her family about her double, but that 2% margin of error turns out to be relevant when her doctor tells her she’s gone into remission and isn’t dying after all. This seems like good news, but unfortunately at this point Sarah’s Double has taken over her life and is living it better than she did, and when Sarah asks to have her clone decommissioned, her double petitions to stay alive. This is when Sarah, who clearly skipped some important points in that infomercial and the fine print in whatever contract they had her sign, finds out that the legal process for that situation is a televised dual to the death to determine who gets to live out the rest of Sarah’s life. She and her double have one year to prepare. Cue training montage (not quite, but she does end up taking hip hop dance classes and working with an equally affectless combat trainer, Trent, played by Aaron Paul of Breaking Bad).

Dual is like a Hunger Games solution to an administrative clone problem. The government can’t have two of the same person running around, and clearly this society has already made it out the other side of the debate about whether clones are real people, have souls, and deserve equal rights, since their solution is to force them to battle it out to the death rather than de facto ruling in favor of the Original. It’s essentially a violent version of flipping a coin. The bureaucrats must have been extra pleased with the solution when they realized they could televise it and make a profit at the same time as they solved their admin issue. Flipping the script on the dilemma so that the humans are actually at risk vs the usual stakes where clones draw the short straw is a very effective way of amping up the ethical discomfort level.

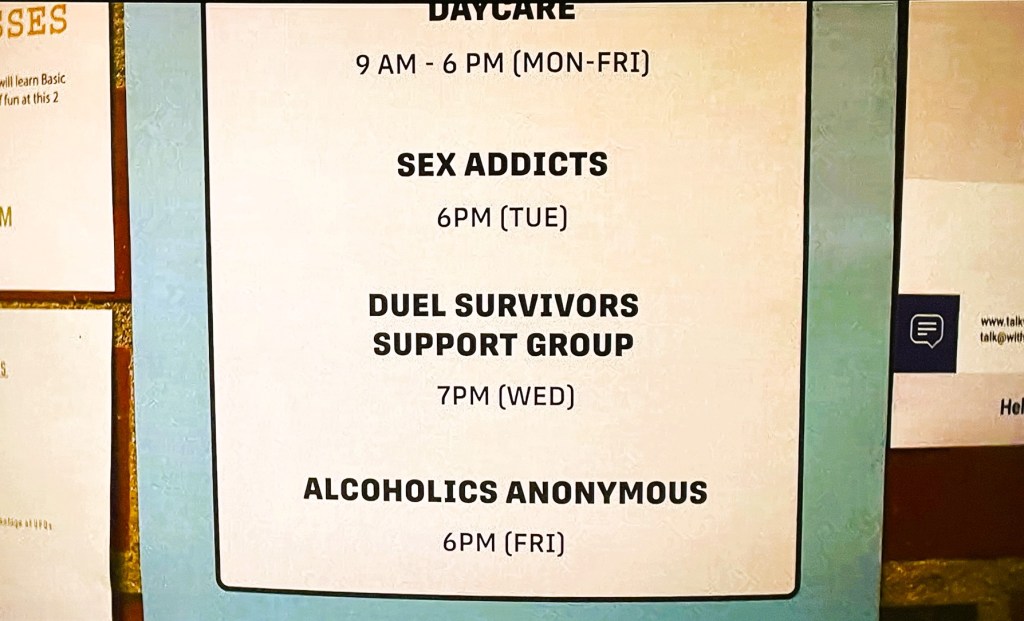

Another thing that amplified the discomfort for me is that stylized emotionally dissociated delivery, which extends to many of the characters in most situations, with the notable exception of when they’re in a contained space alone, or the supporting characters in one of my favorite scenes where Sarah’s Double takes Sarah to a clone duel survivors support group meeting. That one scene gives so much context for everything I had suspected might be a logistical problem with the overall clone process, and also a bunch of emotional context for the whole experience that we don’t get from either of the Sarahs. It’s also very entertaining in a really disturbing way.

I found myself asking why on earth Riley Stearns would choose to direct the actors in that weird way, but after the fact I’ve really come to appreciate it. The things that happen in this film could easily tip over into melodrama if the characters had more standard emotional reactions to them, but it’s very intellectual and darkly comic and the lack of affect keeps it that way. It makes it possible to take the story in more fantastical directions like the clone duel, where more emotionally fraught films like Never Let Me Go or Swann Song could not reasonably go. Swann Song actually has a very similar premise with a terminally ill man who secretly arranges to be cloned so that his family won’t know he’s died, but his clone is exactly like him with all of his memories, whereas the clones in Dual have to learn to be as much like their original as they can (or care to) before their original dies. The infomercial has a disclaimer about that, of course, and strongly implies that people don’t really know each other as well as we like to pretend we do and our loved ones might actually be just as happy or happier with a clone.

Never Let Me Go is a different version of a society that has moved past the question of whether clones are people and have souls. They’ve decided that they don’t care as long as they can use clone organs to avoid illnesses and extend their own lives. It’s a very similar concept to Parts: The Clonus Horror, where clones are raised in an isolated desert colony as a source of replacement organs for rich people, but much more about the tragedy of it than the visceral horror. Never Let Me Go follows three clone children who are raised at a special boarding school to become organ donors for non-clone people until they “complete”, which could be after one or multiple donations. Aside from that, it plays out almost exactly like a sad, dreamy period drama with a love triangle and friendships tested through time, with an extra twist of tragedy because their early deaths are a morally abhorrent foregone conclusion. It ends by posing the philosophical question of whether the clone donors actually lived any less good or fundamentally different lives than other people, while Dual left me processing the dichotomy of how our lives can be worth fighting to the death for even when the circumstances of our lives make us deeply unhappy.

Somehow when I think about the elements in Dual that seem absurd, I realize that they aren’t actually anywhere near as far-fetched as they really should be. Despite the lack of emotional affect and the clones, it all feels oddly emotionally relatable, perhaps because it taps into a more general feeling of disconnection from one’s own life and other people. I’d love to be able to say that the clone duel solution is over the top, but in the context of history and current events it’s barely an exaggeration. All of that said, I don’t think any of the movies I’ve mentioned in my article change the initial thesis statement: clones are pretty much always a problem.

~~~

Alex MacFadyen strongly suspects that if one was ever going to purchase a clone, the one hour, while you wait, buy-now pay-later version is a Very Bad Plan.

Categories: Screen