“And we’ll hate what we’ve lost but we’ll love what we find…”

– from “Featherstone” by The Paper Kites

Sometimes I feel like the joy and value of ephemeral things get lost in an all-consuming preoccupation with things that last. Perhaps it’s rooted in a desire to avoid the eventual loss slumbering within anything good that fades away, or simply an attempt to prevent ourselves from fully vanishing without a trace. Perhaps it’s a desire for a level of certainty that life doesn’t really offer and which we might even become disenchanted with over time. There’s a tendency to treat relationships or life choices that don’t last as failures, but who’s to say that something finite necessarily has less value? The nuanced and charming way the silent animated movie Robot Dreams (2023) explores the profound joy, wonder, and sadness of finding and losing connection with another person is one of the reasons I loved it so much, and also why it reminds me more of the films of Wong Kar-wai than other animated movies like Flow or The Iron Giant.

Robot Dreams is deceptively simple. It’s based on a 2007 graphic novel by American writer/illustrator Sarah Varon, adapted by Spanish writer/director Pablo Berger into a 2D animated film with clean lines and soft colors that give it the feeling of a children’s picture book. It has no dialogue and features robots and anthropomorphic animals, which will probably appeal to kids, but the existential themes it explores are very much for adults who have experienced loneliness, love, and loss. It is both heartwarming and heartbreaking, sometimes at the same time, in a way that feels like real life but I’ve rarely seen captured so effectively in film.

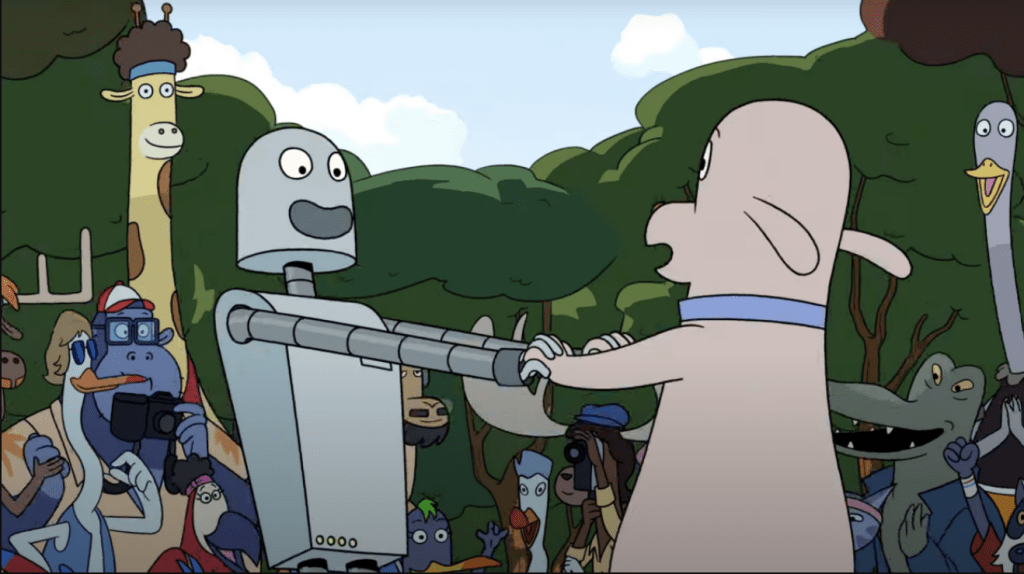

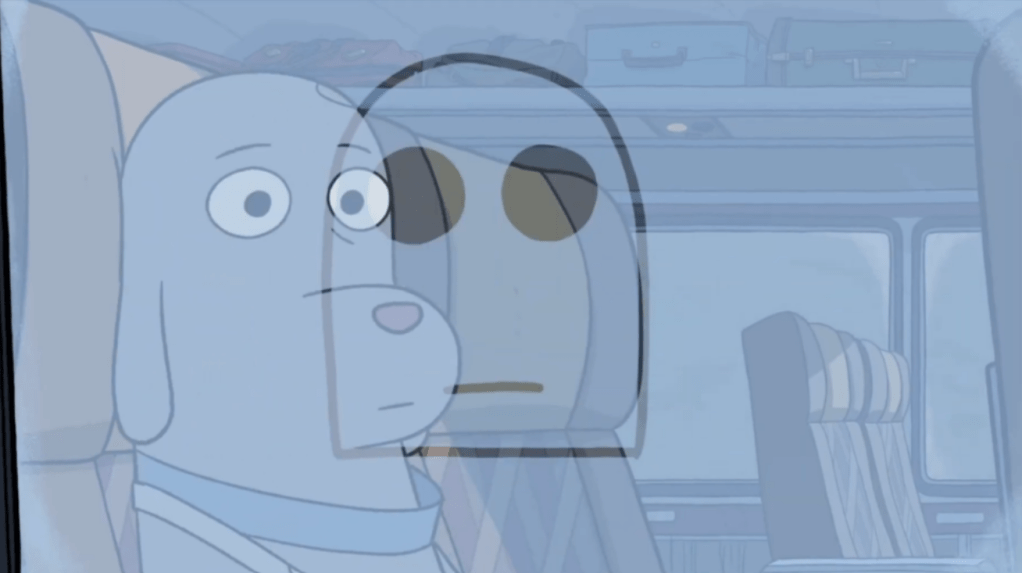

It’s set in New York City in a fictional 1980s where lonely anthropomorphic animal residents can order a robot friend to be delivered to their house, some assembly required. Significant assembly, actually. Dog lives in a tiny East Village apartment in Manhattan, alone. Dog sees their neighbors watching television and making dinner with partners or friends but is left staring at their own solitary reflection in the tv screen at the end of the evening. Then one night they catch an ad for robot friends and decide to order one. From the moment Robot arrives, the two have a connection, and the film goes from shadow to light with a montage of them around town together, doing all of the things that Dog has wanted to do but couldn’t enjoy alone. They even choreograph a dance routine on roller skates to “September” by Earth, Wind & Fire, which becomes their song. It could be friendship, or romantic friendship, or fully a romantic relationship, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s an intense connection with another person, and it feels exactly like the exciting beginning of a new relationship.

Then they go on a trip to the beach at Coney Island [spoiler alert, watch it first if you don’t want to know what happens!] and have a wonderful day in the sand and surf, except that robots are metal and should not surf. Robot rusts up and is unable to move, but when Dog returns in the morning with tools to help, the beach is closed for the season and Dog can’t get past the security gates and guard. Dog applies to the city for access but is denied, so they return to their apartment alone and Robot spends the entire winter frozen in place on the beach. Time rolls by in a combination of lovely illustrations of the passing of the seasons through the fixed lens of Robot’s eyes, interspersed with unexpected interactions with beach wildlife and an anxiety mashup of all Robot’s dreams of being reunited with Dog and worries that Dog has forgotten them or that the magic of their relationship will be gone by the time Dog comes back.

Dog does not forget, but Dog is also not the first person to find Robot and what happens next wasn’t part of Robot’s anxiety loop. Robot ends up being recovered and refurbished by someone else entirely, who Robot finds new ways to have fun with. It isn’t until the very end of the film that Robot sees Dog again from afar, also looking happy with someone else. In that moment, Robot has a choice. Robot’s life literally started with Dog and their longing to reconnect is obvious, but so is their happiness with their respective new friends, and in the end, Robot chooses to move forward from where they are. It’s an ending that really resonated for me because it captured the complexity of having feelings for more than one person without it causing drama or having to erase one to appreciate the other. It’s a view of relationships where happily ever after isn’t the final measure.

Part of the success of Robot Dreams lies in the pacing and the focus on small details. The book version was lovely, but film seems like the perfect medium for it because film controls the element of time. It’s easy to unintentionally speed through a graphic novel with no text, and one of the most powerful things about Robot Dreams is the inescapable experience of the passage of time. From the endless expanse of a life of loneliness where days seem to repeat without variation, to the joyous whirlwind of finding someone who makes you happy and wanting to do everything in the world with them all at once, to the torture of being separated from someone you love and forced to wait helplessly for months not knowing if you’ll see them again, to the experience of one thing you love slipping away and moving on to another, all of these are made more powerful by the medium controlling the pace. We’re forced to experience the discomfort of slowness at points where Dog or Robot get stuck in their lives and are spun along through the exciting parts with the energy of speed.

It seems like it might be most natural to compare Robot Dreams to other animated films featuring animals or robots, such as the silent Flow, the lovely Iron Giant, or The Wild Robot, but what it actually reminds me of is the stylized, poetic films of Hong Kong writer/director Wong Kar-wai. His films explore love, loneliness, and loss with a similar mix of comic charm and melancholy, using slow pacing, stylized visuals, and a close focus on mundane details to reveal existential insights. Robot Dreams reminds me of films like Happy Together and Chungking Express in the quirky way it traces the trajectory of a relationship through a series of small, everyday moments, using long shots that capture a sense of isolation and slow pacing with closeups and music to convey nuances of emotion in the absence of dialogue.

Chungking Express is more an exploration of relationships than a narrative story. The atmosphere and use of poignant but quirky visual imagery make me think of Dog’s lonely pre-Robot life and the winter they are separated in Robot Dreams. The film focuses on two police officers, identified by their badge numbers, who are in the aftermath of relationship breakups. Alone in his apartment, Cop 663 (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai) talks to his bar of soap, commenting on how it’s lost a lot of weight and should have more confidence in itself. He admonishes his washcloth not to change itself just because his girlfriend has left. “You have to stop crying, you know. Where’s your strength and absorbency? You’re so shabby these days.” Wong Kar-Wai’s characters examine mundane objects like a dishrag or soap in ways that transform them into metaphors for unrequited longing and sadness.

Cop 223 (Takeshi Kaneshiro) split up with his girlfriend, May, on April Fools Day. He decides that every day for a month he will buy a can of pineapple, her favorite fruit, with an expiry date of May 1st and if she hasn’t come back to him in 30 days then their relationship will have expired as well. He takes lonely nighttime walks around the city, searching for increasingly hard to find cans of nearly expired pineapple to measure his days. By the end of the month, the store clerk has removed the remaining cans from the shelf and doesn’t want to sell them to him, but he argues passionately on the pineapple’s behalf, saying it’s wasteful and chastising the clerk for preferring new ones without considering the feelings of the old cans. On April 30th, after discovering that May has found a new boyfriend rather than returning to him, 223 consumes all the pineapple cans one by one. He seems to enjoy them at the time but later they give him a stomach ache, because of course they do.

Happy Together is more a character study of an individual relationship between Lai You-Fai (Tony Leung) and Ho Po-Wing (Leslie Cheung), through multiple breakups. Unlike Dog and Robot, their relationship is somewhat toxic, but there is still something about the structure and feel that remind me of Robot Dreams. It examines their relationship in slow, close detail, with the first 20 minutes where Fai describes their current break up shot largely in black and white, much like Dog seems to spend their pre-Robot life cast in shadows. Then, like Dog’s world once Robot arrives, Happy Together comes to life in brilliant color as soon as Po-Wing asks Fai if he would like to start over.

I think what I love so much about both Robot Dreams and Wong Kar-wai’s films is their ability to evoke complexity through imagery, allowing multiple conflicting feelings to co-exist at once without requiring me to push one aside in favor of another. Life is so much fuller and more rewarding when we make space for everything to exist in its own way.

~~~

Alex MacFadyen hopes he never spends a winter rusted on the beach.

Categories: Screen