Guest Star and film scholar Earl Jackson continues his look at Kimi wa Koibito / You Are My Lover, a dizzyingly metafictional and genre-bending Nikkatsu film featuring an injured Japanese teen hearthrob’s return to the screen in a movie that references his injury and the incident that caused it. Read Part I here.

~~~

Recap: Hamada Mitsuo was a teen idol superstar beginning in 1960. In 1966, however, he was collateral damage in a bar attack in which a glass shard penetrated his eye. You are My Lover is his comeback film after more than a year’s convalescence. In Part One, I discussed the significance of the Nikkatsu stable of stars appearing as varying degrees of “themselves.” In Part Two, I deal with the film’s peculiar attitude to the narrative it presents.

It is challenging to summarize You Are My Lover because any statement about the plot must be made tentatively as it will likely have to be qualified or even negated as the film advances–this includes descriptions of both the framing narrative and the core story. With that in mind, here we go

The opening is split into two frames. Hamada’s arrival at Nikkatsu studios and his preparation for his first scene reads as “real.” When he appears on the set, however, Ishihara Yujiro taking the role of director “Ishizaki” marks this as the fictional level of making You are My Lover. The final framing of the film, however, is even more complex and is not symmetrical with the first framing device.

The core plot of the film being made involves a young Mitsuo, who, tired of his job at the Ishido factory, decides to join the Ishido-gumi yakuza gang, which leads to disaster. However, the progression of the narrative is interrupted several times and ultimately leads to major revisions of events already presented. After two takes of a scene in which Mitsuo walks down a street (on a sound stage) and bumps into a woman, the screen freezes, Hamada sings the title song in voiceover as the credits roll.

When the screen unfreezes, Hamada hurries through the actual Shinjuku then transforms instantly into his character Mitsuo on a soundstage version of a Shinjuku street where he bumps into a woman carrying food deliveries from a ramen restaurant, causing her to drop them. Masako (Izumi Masako), the owner of the restaurant, emerges and Mitsuo washes dishes to compensate for the destroyed orders. Taking a profound interest in Mitsuo, Masako pursues him tirelessly, even as he rebuffs her with increasing brusqueness.

Mitsuo hurries to meet his mentor, the low-level yakuza Konpei (Hayashiya Konpei). Meanwhile, trouble is brewing in the Ishido-gumi, as the current boss (Shishido Joe) sees himself more as president of the factory than kumi-chō of the latter, much to the chagrin of his second-in-command, Ono (Toda Akihisa) and his men. They encourage Ishido to go abroad and plan to restore the gang to a more formidable status through strategic killings and other acts of violence instead of the production of their cover business.

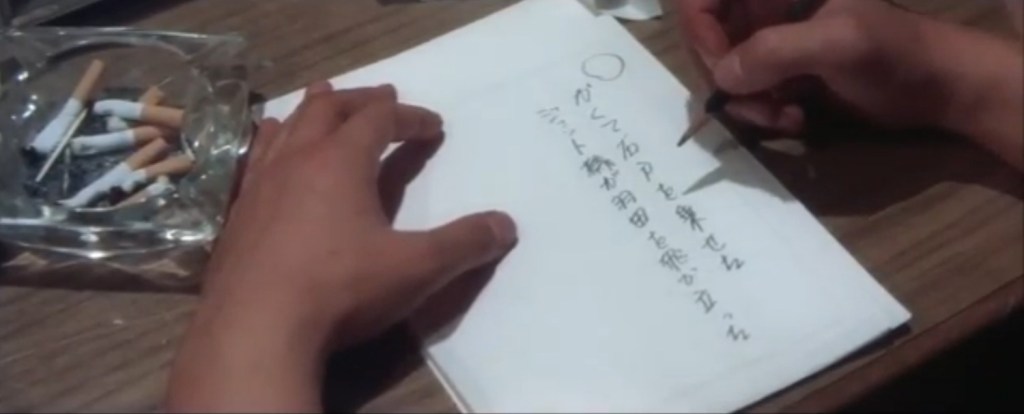

The shot of Ishido’s jet taking off is followed by a cut to a close-up of a hand writing: “The jet carrying each of the Ishido family members took off from Haneda Airport.” The hand belongs to the screenwriter for the film, Akai (Watari Tetsuya). Akai takes a break from his dissatisfaction with the dialogue by going bowling. Although Ono’s plans sound ominous on the level of the plot, the danger is mitigated meta-cinematically when Akai gets a call at the bowling alley from a producer who complains the script so far is too cruel and insists Akai soften it.

The official Nikkatsu Studio plot synopsis includes scenes in which singer/actors Araki Ichirō and Funaki Kazuo learned of the film being made and asked the producers to include them. Although these scenes did not make the final cut, the actors’ wishes were granted. In Part One I described Araki’s encounter with the Ishido-gumi after singing. Funaki has a more direct involvement with Mitsuo and the scene itself seems to reflect the producer’s request to soften the plot. Funaki plays Mitsuo’s former workmate, Funayama, whom Mitsuo encounters in a barren playground at night. The tenderness Funayama expresses suggests a homoeroticism not elsewhere in the film.

Mitsuo: Funayama – what are you doing here?

Funayama: I was waiting for you?

Mitsuo: Why? We don’t have anything going between us.

Funayama: Come back to the factory.

Mitsuo: Did the factory ask you to do this?

Funayama: No. You and I have always worked together. Now that you’ve stopped coming, I’m so lonely.

Funayama pleads with Mitsuo.

Mitsuo: I’m not lonely.

Funayama: Don’t you remember how we would sing together by the canal in the factory?

Mitsuo: [silent but moved by the reminder].

Funayama: I’m going to sing for the first time in a long time, so please remember this.

He sings “Ai ni tsutumarete:, / “Surrounded by Love”, which became one of the notable B-sides in Funaki’s discography. The first line seems to continue his statement, however far more flamboyantly: “Lift your face, like flower petals up to me.” While Funayama sings, Mitsuo moves around the grounds as Funayama follows him.

“Lift your face, like flower petals up towards me”

“Our two dreams will merge sometime”

When Funayama sings the lines, “two who trust each other/who love each other/in the marvelous night, the breast trembles.” Mitsuo turns to him and says, “Funayama–I’m not coming back. At the factory you can wait and wait and get nothing. But there is opportunity out there and I’m going to grab it. Goodbye,” and runs off. Funayama calls after him but suddenly reappears in a cabaret singer’s suit that resignifies him as Funaki, who finishes the song with the star-filled night sky as backdrop.

Funaki’s appearance also serves an intertextual purpose. For most of the film, Izumi Masako’s “Masako” has very little to do, mostly managing her ramen shop and chasing an intransigent Mitsuo whose weird lack of charisma makes her devotion rather quizzical. Funaki metonymically reminds the viewer that Izumi is a huge star with great on-screen presence. The two of them made many films together and their chemistry is reflected in their nickname, “the golden couple”. One year prior to Kimi wa Koibito, the two starred in a blockbuster melodrama, Zesshō / Last Song. The traditional term of “melodrama” in Japanese is namida chōdai geki–“’your tears, please’–theater.”Last Song takes an industrial plunger to the tear ducts. Funaki plays Junkichi, from a wealthy landowning family who falls in love with Koyuki (Izumi), the daughter of tenant farmers. He is disowned and the pair flee to the Inland Sea where they set up housekeeping, supported by their progressive friends. When Junkichi is drafted, Koyuki overworks and contracts tuberculosis. Junkichi arrives at Koyuki’s deathbed and promises she will be officially married before burial. The final scene is the regal wedding Junkichi gives his late bride .

The contrast between the deep emotions of that Funaki scene, underscores the strange suppression of human feeling in Mitsuo’s character inYou Are My Lover. Mitsuo goes further into the dark side when he volunteers to kill a rival gang boss just released from prison. Hesitating to shoot led Mitsuo and the intended victim into a fight, but once the boss was backed into a corner, Ishido’s second in command, Ono, and his men appeared from above and Ono delivered the fatal shots, while Mitsuo hugged a wall in horror. Nevertheless, Mitsuo was paid, and afterwards he took on a yakuza-style swagger that only partially hid his anxieties.

Mitsuo’s quandary plays out on two levels: on the level of the plot–that of a young man in over his head, on the level of the film–a character who suspects he’s in the wrong genre. The film itself takes a break from Mitsuo’s dilemma, cutting to a publicity photo session for the rock group, The Spiders. As it turns out, Hamada is in the next photo studio, shooting a promotion for a new pencil.

The Spiders ask Hamada about how the film is going and he invites them to watch the climax by closing their eyes and listening. At his signal, the film returns to the plot. The first interruption in the plot involved the screenwriter Akai and the process of making the film. This interruption involves Hamada supposedly as himself in real time parallel to the making of the film. However, the “realism” of the encounter is displaced by Hamada’s conjuring the rest of the film in the mind’s eyes of the Spiders.

The resumed story begins with the singer Inoue Shigeru (Katsumi Shigeru) performing in the Shinjuku streets, which angered the Ishido-gumi running a protection racket for singers in the area. In Part One, I described Araki Ichirō’s encounter with the gang, and the Johnnys’ attempt to support Inoue by also daring to perform in the neighborhood, unsanctioned. This time, the gang marked Inoue for death and gave the assignment to Mitsuo who stalked Inoue into the park, stabbed him and left him dead, floating face down in a fountain.

When Mitsuo returns to the bar hangout, he overhears one of Ono’s men admitting that they intend to set Mitsuo up for the crime and deny any connection. Mitsuo bursts in, fatally stabs the gang member, and heads for Ono’s office. There he kills Ono’s other assistant, and stabs Ono who manages to stab Mitsuo before dying.

Masako and Konpei arrive and huddle around Mitsuo. But then a voice shouts, “That won’t do!” and Konpei looks up as if a voiceover occurs physically above the site. The film cuts to the Spiders and Hamada eating ice cream in a café where the Spiders voice strong objections to the narrative and vow to get Akai to change the script.

Akai is astonished at such a request. He says that You Are My Lover is an art film that cannot be altered and he is too busy writing for television to even consider it, then throws them out. The Spiders tperform loudly beneath Akai’s window for two nights until Akai relents. Akai writes: “Drawing on the power of his former colleagues, Mitsuo attacks Ishido Industry’s main headquarters, the nightclub Shiro.” The scene changes to the nightclub featuring a nearly naked dancer, when suddenly Mitsuo and the Spiders appear on the stage and begin fighting the Ishido-gumi. Ono and his main assistants are now alive and unharmed but they are defeated. The staccato editing, cartoon-like fight choreography and the garish setting recall the climaxes in the 1966-8 ABC-TV Batman series. This is no accident. The series was broadcast in Japan at the time and the theme song was done by another Johnny Kitagawa boy band that, like the Johnnys before them, had Kitagawa’s name as part of theirs: Johnny’s Jackey Yoshikawa and his Blue Comets.

The scene changes to a large theater, with a packed audience applauding Sakamoto Kyū’s bubbly entrance on stage. Sakamoto shot to international fame in 1962 with the song “Ue wo muite arukou” / “I will walk looking up,” although in the English-speaking world it was incongruously retitled, “Sukiyaki.” The scene is apparently Sakamoto’s TV show, Kyū-chan!, in which he interviews a singer and sings with them. Here he introduces Hamada (without actually saying his name) as “a person who has endured a cataclysm and has fought back to a full life.” When Hamada runs out, Sakamoto asks him how he is and if the lights are too bright for him, a clear reference to a difficulty that Hamada was actually having long after his recovery. Sakamoto then announces that they will watch the final sequence of You Are My Lover.

The sequence includes a scene in a hospital room in which Mitsuo is treated for his injuries acquired in fighting Ono, sharing the room with Inoue, who in this version survived Mitsuo’s knife attack. Inoue refuses to press charges, and forgives Mitsuo, saying “Everyone deserves a second chance.” But since Mitsuo’s killing of the Ishido gang was erased, why was his attack on Inoue retained? The scene will take on a dark irony retrospectively. As I mentioned in Part One, Katsumi Shigeru, who played Inoue, in 1976 strangled his mistress and left her body in the trunk of a borrowed car. He was sentenced to ten years in prison, but was paroled in 1983. Katsumi also was inexplicably given a “second chance” and booked on a tv variety show, but popular outrage ended that.

In Part One, I focused on stars who appeared as themselves. The cameos in the hospital scene offer a variation on that in that the superstars cannot help but appear as themselves as their celebrity outshines these minor roles, further undermining the narrative as they derail any realism the scene might have had.

Masako expands Mitsuo’s second chance by introducing him to a record company executive (played by Hayama Ryōji, the intended target of the attack that wounded Hamada). Mitsuo’s recording session/audition is attended by Hayama and the producer played by “Mighty Guy” superstar Kobayashi Akira.

The film cuts to a medium close-up of Sakamoto and Hamada. Sakamoto says that the sequence moved him greatly as the story of a yakuza thug becoming a decent person resonates with Hamada’s recovery from his medical difficulties. Thus, You Are My Lover not only examines itself but analyzes it too. The pair then sing the film’s theme song together. The duet recalls another important connection between the performers. “Ue wo mite arukou” was originally the title song of a film starring both Sakamoto and Hamada. Although the melody is upbeat, the lyrics are melancholy and the film focuses on young criminals. In the opening of that film, Sakamoto and Hamada escape from prison, and at the end, the true friends beat each other to bloody pulps and are on the verge of killing each other before the intervention of Yoshinaga Sayuri.**

Duet of the title song, live on stage . . .

. . . and mediated through television.

There is a detail in the shot before the duet, however, that complicates You Are My Lover’s final framing, as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay. When they begin to sing, there is another shot of the audience, but now Izumi Masako as the character Masako is in the front row, which folds this musical reality back into the film’s fiction, like a Moebius loop. The film cuts to Masako throughout the duet. At the end of the number a close-up of Sakamoto and Hamada’s handshake dissolves into Hamada’s and Izumi’s clasped hands as they run through empty Tokyo streets as the title song plays them off. Mitsuo completely ignored Masako throughout the film and even disparaged her as “a meddlesome woman.” But the final shot demonstrates the function of genre to generate a romantic closure to vindicate the title song..

Hamada Mitsuo’s comeback film becomes a meta-cinematic celebration of the star power of both Hamada and all those celebrities who appeared to support him. Beyond the PR, however, the film’s experiments intervened in its own ontology: the nature of the “being” of the onscreen figures, and its own epistemology. How do we know “what happened” when events are subject to negation and revision. We are left with a cinematic fantasy and a fantasy-cinema permeable to its own metafictional concoctions.

*See Part One for the description of the Johnnys and the history of Johnny Kitagawa’s sexual abuse of his male stars.

**Yoshinaga Sayuri was Hamada’s co-star in many “pure love” films between 1960-1966. See Part One on how her image functions in You are My Lover.

~~~

Earl Jackson lives in southern Taiwan by an ocean-bound river that flows backwards at high tide. Jackson’s cinephilia began the evening that his mother took him to see The Creature from the Black Lagoon at the Ellen Terry Theater in Buffalo, New York. His favorite phrase is “a conversation in progress.” Jackson believes that paying attention is an ethical imperative that also makes life a lot more interesting.

Categories: Guest Star, Screen

1 reply »