I have long wanted an ancestral portrait painted in a German Expressionist style hanging in my entry when I greet weary travelers seeking shelter from a ferocious storm. They would evince surprise at the unnerving resemblance between that sinister visage and my own features or perhaps those of one of their companions.

“No, I hadn’t noticed the resemblance before,” I’ll say, raising my candelabra higher to peer more closely at the portrait. “Remarkable. Yes, quite uncanny.”

Perhaps you’ll be that traveler unsettled by the portrait, how much it resembles you or me or your partner. Those paintings always turn out to be, at best, ill-omened.

So I suppose it is fortunate for us all that I do not yet have a creepy ancestral portrait.

It is unfortunate for us all, however, that filmmakers have generally stopped using spooky, uncanny, or malevolent paintings in film, The Devil’s Candy (2015) and Velvet Buzzsaw (2019) aside. I like art and horror, so it’s a convention I enjoy. I still remember the revelation of the portrait in The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1945)–the sudden burst of color as we gaze upon the corrupted painting itself. I have seen that very painting, “The Picture Of Dorian Gray” by Ivan Albright, at the Art Institute of Chicago and can report it is indeed disturbing in person. And I am fond of the Candyman mural in Candyman (1991) and how wrongheaded grad student Helen (Virginia Madsen) emerges from the Candyman’s mouth. (Signification, baby!) But I think the height of sinister paintings on film and television was in the 1960s–especially the ones in Roger Corman’s Poe Cycle. Corman writes that after learning his craft making very low budget, black and white movies in the 1950s

I was ready to move on to bigger, better movies on longer schedules and to direct more experienced actors from better scripts. The chance to do all those things came in the visually and thematically rich gothic horror genre. I directed a ‘cycle’ of eight films shot between 1960 and 1964. These films were adapted from the often macabre, psychologically unsettling imagination of Edgar Allan Poe, whose poems and stories I had enjoyed immensely as a youth….I felt that Poe and Freud had been working in different ways toward a concept of the unconscious mind, so I tried to use Freud’s theories to interpret the work of Poe. Usher had many of the elements that became standard fare for the Poe films.

How I Made A Hundred Movies In Hollywood And Never Lost A Dime, 77-8

The Poe Cycle films look expensive, lavish and glorious. The first film of the cycle, The Fall Of The House Of Usher / House of Usher (1960) is a remarkable transition from The Wasp Woman and Bucket Of Blood, both released the year before. Though there is some carryover as Bucket reflects the Bohemian circles Corman intersected and his interest in the arts. One of the most intriguing elements of the Poe films, and something worth noting given how notoriously thrifty Corman was as a filmmaker, was that Corman commissioned original paintings for the Poe films rather than using existing art. After all, the House Of Usher is stuffed with Baroque and Rococo tchotchkes, art and furniture and Corman could have used some already extant period paintings instead. Footage, set pieces and props from House of Usher itself and from other films were recycled in later Poe films, but the films using paintings to reflect the protagonist or antagonist’s unconscious and its horrors had unique paintings created for them.

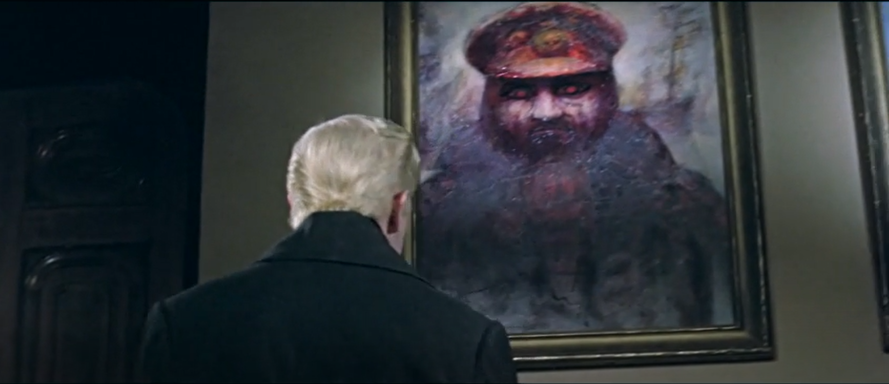

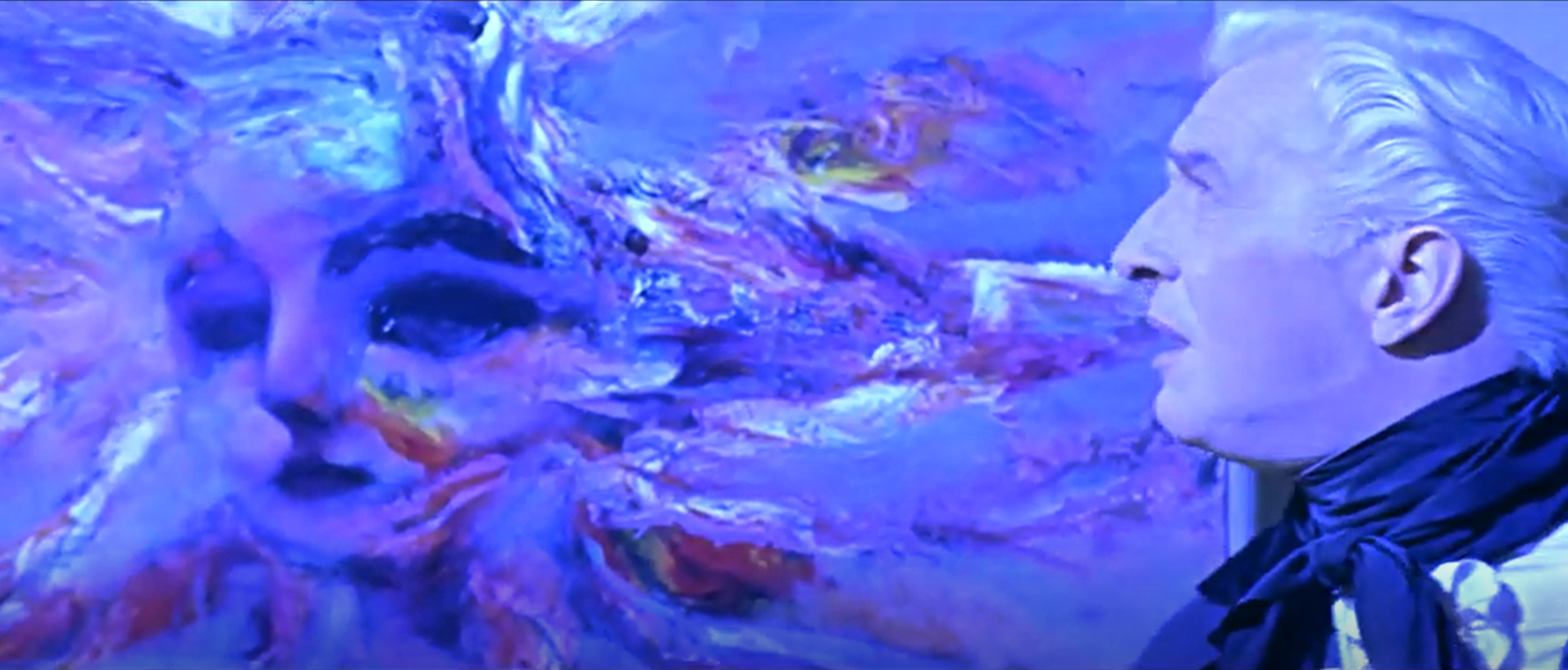

The paintings allowed for exposition, as when Roderick Usher (a platinum blonde Vincent Price) attempts to frighten away Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon) with stories of the Usher family’s depravity, madness and curséd bloodline. In The Raven (1963), Dr. Erasmus Craven (Price) stands before a portrait of his wife Lenore (Hazel Court) and mourns her loss, before everything turns comic with the arrival of the raven, voiced by Peter Lorre. And in The Haunted Palace (1963),* the portrait of Joseph Curwen allows his descendant Charles Dexter Ward (Price again) to have an object of fixation as he battles to save his mind and body from possession by the long deceased sorcerer. In films without creatures—where the horror resides in places, histories and human beings—the paintings express the hidden, the uncanny, and the unconscious.

The paintings in these films are always striking and gain additional impact from their seeming anachronism.** But the works are not anachronistic as a failed attempt to recreate the past by furnishing a castle of horrors within budget and time constraints. And this anachronism is not a result of ignorance. The art is deliberately and pointedly not of its time and all the period appropriate set-dressing the art is set against serves to heighten an effect of controlled dissonance. The paintings stand out for their German Expressionist, Cubist, and/or Surrealist feel in Victorian, Colonial, Italian Renaissance and Medieval settings. The films feel very much like the contemporaneous Gothic Hammer horror movies—until Roderick Usher gestures toward eerie portraits of his ancestors in lurid colors with black and red eyes and all rendered in a style intended to disquiet in contrast with cherubs, knights, pages and all the usual period objects dressing the set. Some of these paintings are more 1960s book illustration in style—for instance the portraits in The Pit & The Pendulum (1961) and the anthology film, Tales of Terror (1962). The Pit & The Pendulum is set in 17th Century Italy and the portraits of the sadistic Sebastian Medina and Elizabeth (Barbara Steele), the dead wife of Nicholas Medina (Price), are very much 1960s Gothic illustration.

While they are not my favorite of the Poe Cycle paintings, they still have a startling impact. These paintings are a reminder that the films are not attempting to immerse us in the past. The paintings help immerse us the minds of their tormented characters, especially the mind of Vincent Price’s characters.***

Among my favorite of the paintings are the Modigliani-esque portrait of the lost Lenore that Craven pines over in The Raven (1963). There is also the Van Gogh-ian portrait of the cruel Joseph Curwen in The Haunted Palace. And I am very fond of the painting of a woman’s face ostensibly by Roderick Usher and the Usher ancestral portraits. It’s tangential, but I also love Francis Rodker’s paintings for the opening credits of The Tomb Of Ligeia (1964).

I like some more than others, but they are all quality paintings revealing Corman’s taste and sensibility in arguably his most personal films. They are the kind of paintings that someone active in the art world of 1960s Los Angeles would choose.**** And it’s fascinating, to me at least, to think of Corman in this context and in these Bohemian circles. Always supportive of an artistic vision, Corman commissioned paintings from artists in their own styles, that would still serve the stories and themes in his scripts. One of them was Burt Shonberg. Corman commissioned paintings from Shonberg for House Of Usher and Premature Burial (1961). Corman writes:

As two artists moving into new modes of expression in our work, our introduction was fortuitous. While Burt’s paintings and murals hung in cafes around Los Angeles, he also had his own spot, the Café Frankenstein in Laguna Beach, and his preoccupation with monsters, aliens, the occult and other horror elements in his art resonated with me. Most importantly, I could see he was a major talent, exploring new ground in form and color. I knew right away that Burt’s artistic sensibilities would lend much to my new film, thus I hired him to create the portraits that adorned the Gothic mansion occupied by Vincent Price’s character in House of Usher. Burt’s work had a mystical, mysterious quality, and was perfect for capturing the evil inherent in the faces of the Usher family ancestors. I provided him with character histories and let his imagination roam free.

Beyond the Pleasuredome: The Lost Occult World of Burt Shonberg (2021)

Aside from the five amazing ancestral portraits in House of Usher, Shonberg also provided 2 canvasses that were to have been painted by Roderick Usher. Like Usher’s almost inaudible, plinking lute compositions, the paintings are meant to illustrate Roderick’s disturbed state of mind, his fear of his familial manor, and his incestuous and probably necromantic obsession with his sister Madeline (Myrna Fahey). The first was a painting hung over the parlor fireplace, depicting the Usher mansion. The second was a stunning, work-in-progress depicting a haunting image of a woman’s face. For Premature Burial, Shonberg provided two paintings for Guy Carrell (not Vincent Price, but Ray Milland), an artist terrified of the prospect of being buried alive. One was the image of a decaying face. The other was a tour-de-force canvas with a stained glass feel depcting a hellscape featuring Baphomet, a guillotine, a crucified person and an array of instruments of torture. In the film, Carrell informs his wife Emily (Hazel Court) that it is entitled, “Sin Consummations Devoutly to be Wished.”

Shonberg was a graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and moved to Los Angeles in 1957. He was a denizen of the city’s Beat coffee houses and its psychedelic scene. Aside from the quality of his art, Shonberg is likely remembered and researched more fully in film and horror circles than the other painters who contributed to the Poe Cycle at least in part because of the remarkable company he kept and his own fascinating biography. Aside from his work for Corman, Shonberg was also an associate of Famous Monsters of Filmland editor and Ur Nerd Forrest Ackerman. He knew Elizabeth Case, former Disney animator, poet and Beat icon. And he was acquainted with George Van Tassel, the ufologist, alien contactee, creator of the Integatron, and recipient of advanced Venusian knowledge from the Space Brothers.

Shonberg co-owned the aforementioned Café Frankenstein with writer George Clayton Johnson. The cafe was decorated by Shonberg and featured a remarkable faux stained glass mural of Frankenstein on its bay window. The cafe received complaints for this mural and for the artistic doings inside from the Women’s Church League, but they backed down when Shonberg “threatened to erect a crucified dummy of Frankenstein’s monster outside the premises[.]” (Wormwood Star, 164)

Shonberg also had a relationship with Cameron, aka, Marjorie Cameron, an artist, poet, actor and practitioner of Aleister Crowley’s Thelema, among other occult doings, who had been married to rocket scientist and Thelemite Jack Parsons until his death. Cameron appeared as the Scarlet Woman and Kali in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954/1966/1978). She also appeared as the woman in black who haunts Curtis Harrington’s uncanny Night Tide (1961). While it was an independently produced film, Night Tide was loosely based on Poe’s “Annabel Lee” and was distributed by American International Pictures as a double feature with Corman’s The Raven (1963). Harrington also directed a short film, Wormwood Star (1955), featuring Cameron and her artwork.

Before meeting Cameron, Shonberg had a profound mystical experience where he was suffused with a Great Light and believed he had experienced full consciousness and the true nature of reality. In Wormwood Star: The Magickal Life of Marjorie Cameron, Spencer Kansa writes how Cameron influenced Shonberg. “Inspired by his new mate, Shonberg became fixated with UFOs and extraterrestrial forces, and began the habit of ritually burning his own art, to prove how unattached to it he was. It was art made to communicate, not to be decorative. Another major thing Cameron did was introduce her lover to the writings of Crowley, as a guide to help him find his way.” (165)

Shonberg and Cameron lived together in a desert ranch with a name formed from parts of their own names, Eronbu. They pursued their artistic and esoteric projects for a time, then broke up shortly after the filming of The Fall of the House of Usher and Night Tide. Shonberg retained an interest in the iconography of the occult, but did not embrace Crowley’s teachings. He continued to pursue the Great Light he had experienced through psychedelics and the Fourth Way system of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. Shonberg submitted no more canvasses to Corman and had only one show in his own lifetime. There was a posthumous retrospective of Shonberg’s work at Cleveland’s Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick in 2021. It included a catalog with images of Shonberg’s work, as well as a tribute from Roger Corman.

Now if you excuse me, I must return to my work.

* AKA, Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe’s H. P. Lovecraft’s The Haunted Palace,

**I say seemingly anachronistic because there were, of course, people outside the norms making their weird art even in eras focused on realism and figurative art.

***This feels especially appropriate given Price’s own background in art history.

****I was not shocked to discover that Corman himself painted.

Some sources:

Roger Corman with Jim Jerome. How I Made A Hundred Movies In Hollywood And Never Lost A Dime. (DaCapo Press, 1998)

Beyond the Pleasuredome: The Lost Occult World of Burt Shonberg (Cleveland: Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick, 2021).

And thanks to friend of the Gutter Kate Laity for sharing Spencer Kansa’s Wormwood Star: The Magickal Life of Marjorie Cameron (Mandrake of Oxford, 2020)

The only mention of any of these artists in Vincent Price’s I Like What I Know: A Visual Autobiography (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1959) is by Richard Matheson. In his introduction, Matheson mentions he had commissioned a painting of Atlantis from Shonberg and shared a nice anecdote about Price referring to the Usher ancestral portraits as “just plain folks” (9). But then the book was published in 1959, a year before Price starred in House of Usher.

~~~

Carol Borden would very much like a coffee table book of paintings from AIP’s Gothic films, thank you.

I, too, saw “The Picture Of Dorian Gray” by Ivan Albright, at the Art Institute of Chicago – but I was too busy squeeing with delight at seeing what was basically a movie prop getting its rightful place in an art museum to be “creeped out”.

One of my soapboxes is that one should not consider the reasons behind the creation of an artwork when determining its “greatness”. Just because someone paid for it, just because it was made for purely financial reasons, does not automatically mean it’s artistically valueless. Why does Andy Warhol get the credit for being a Great Artist when he literally just copied the labels of soup cans for his “masterpiece”? Don’t the people who actually created that label design deserve at least some credit? And the Great Artists of the past were just as interested in money as anyone. Rembrandt didn’t paint “The Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild” because he thought it would be a cool thing to do; he did it because the Guild asked him to and paid him for it.

LikeLike

I forget if you inspired this idea, or if you encouraged it, or if it was something I came to you with, but I do, indeed, want an “ancestral” portrait of my own-the portrait of the “first” “doomed” director of the library I work in. Some September 23rd I’m going to “discover” it in the archives and hang it and wait for people to note the uncanny resemblance.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes! YES!

LikeLike

I could not love this piece more. Thank you for bringing it into the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. It means a lot coming from you!

LikeLike