Wait, was that real? It’s a question I ask myself more and more often as I whirl around in the blender of art, tech, media, propaganda, and sales pitch that beams into my eye and ear holes from all the electronic devices I own. The lines between news and opinion, media and advertising, documentary and fiction have become seriously overlapping Venn diagrams, which results in both a lot of confusion and misinformation on one hand, and some very creative and interesting art on the other. So many of the things that have been happening in the world lately have left me questioning what actually works as a spoof, shenanigan, or social commentary in a climate where even the most extreme and absurd stories are virtually indistinguishable from reality. What do filmmakers have to do now in order to make real things feel real to audiences, and how ridiculous can something fake get before audiences – or to blur the lines, sometimes even participants – realize that it’s not real?

Filmmakers approach that fake-real balance in so many different ways. There are self-aware mockumentaries where the audience is in on it all along, like the clever satire of Christopher Guest’s Best in Show (2000) or the ridiculous spoofiness of Andy Samberg as a boyband heartthrob in Akiva Schaffer and Jorma Taccone’s Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (2016). There are blends of fact and fiction where the audience clues in partway through, like the wonderful fanfic universe that Weird: The Al Yankovic Story spins off into with its Madonna crime lord storyline. (Going in I hadn’t realized that it wasn’t fully a biopic, but in retrospect, what else could I possibly have expected from Weird Al?) There’s reality television, where it’s theoretically all real except that the circumstances are artificially manufactured and everyone’s behavior is altered by the presence of the camera, or wrestling, where it’s heavily rigged and rehearsed but fans often want to believe it and engage with it as if it’s real. There are mockumentaries that people mistook for real documentaries, and ones that the filmmakers made a genuine effort to fool people into thinking were real. And then there’s the strange and surprisingly lovely hybrid that is Jury Duty (Amazon Freevee, 2023), where only the star of the show doesn’t know he’s not in a real documentary.

Mockumentary is the art of making something fake seem real while simultaneously impressing audiences with how cleverly you’re faking it. It’s conceptual and takes a lot of skill, but it’s also frequently very foolish and total balderdash, so is it high art or gutter? Over the last century, attitudes toward fake documentaries have shifted away somewhat from a stance not unlike Plato’s suspicions of imitative art in The Republic, where he essentially argues that a painting of a carpenter might be mistaken, by a small child or a simpleton, for a real carpenter and clearly that would be bad. This is presumably not a situation that occurred to Plato, but it reminds me of the hilarious Star Trek-style spoof, Galaxy Quest (1999), where the alien Thermians have constructed all of their technology and travelled to Earth to seek help from the crew of the starship NSEA-Protector based on “historical documents” beamed through space, which are actually episodes of an old sci-fi tv show.

Gwen (actor): They’re not ALL “historical documents. Surely, you don’t think Gilligan’s Island is a…

Mathesar (Thermian): Those poor people.

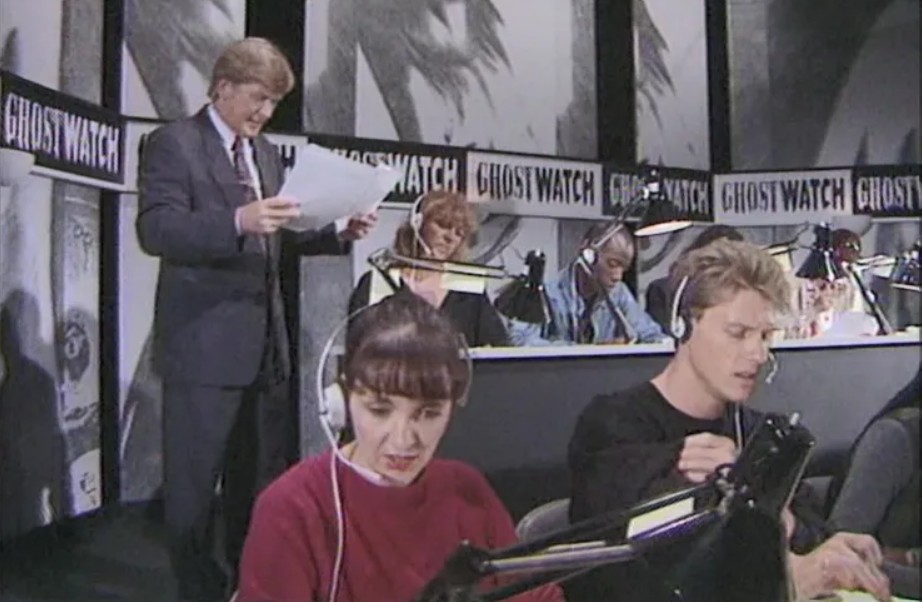

There have been a few examples where people were taken in by mockumentary programs, such as the 1938 radio dramatization of Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds alien invasion (which I wrote more about in Science, Fiction, and Science Fiction Hoaxes), or the live ghost hunt in Lesley Manning’s very realistically filmed 1992 BBC Halloween special Ghostwatch, that genuinely fooled people and reportedly caused some level of mass hysteria despite disclaimers stating that they were fictional. There are also some examples where the filmmakers made a genuine effort to temporarily trick audiences as part of the experience, like The Blair Witch Project, which involved the creation of websites, fake interviews, and IMDb pages for characters listing them as missing and presumed dead. In Jury Duty, the twist is that the audience is in on the secret from the beginning as the cast and crew execute an elaborate mockumentary hoax around one unsuspecting real person.

The setup for Jury Duty is that the lead in the show, Ronald Gladden, answered an ad on Craigslist asking for people who would be willing to be filmed going through jury duty for a documentary film and has no idea that the whole experience is scripted and everyone else is an actor. The show also stars actor James Marsden as an asshole version of himself, whose staged attempts to get himself released from jury duty result in the jury being sequestered for the length of the trial, thus creating a fully closed environment for a 3-week-long semi-improvised practical joke. The show’s creators, Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsk, were both writer/producers on The Office and it really shows in the hilarious situations and trials they put Ronald through. The set is extremely cleverly designed in order to secretly film Ronald from multiple angles in addition to the cameras he actually knows about, and the cast and writers have to be constantly on their toes and willing to flip the script daily or on the fly based on whatever choices he makes. I figure the storyboarding must have resembled one of those choose your own adventure books, where you go to page 12 if he remains calm, page 37 if he freaks out, and back to page 2 if he starts getting suspicious.

There are some serious ethical considerations involved in playing a 3-week long televised prank on an unsuspecting person who can’t actually consent to it, and the whole thing could have been extremely uncomfortable or come off as mean-spirited if Ronald hadn’t turned out to be such an endlessly kind, patient, conscientious, trusting human being. No matter what mad or maddening things they throw at him, he always does his absolute best to help his fellow jurors, accept them for who they appear to be, and make the best decision he can on the utterly bananas case that is presented to him. The creators and cast did a wonderful job of never making Ronald the butt of the joke, but it must have been increasingly difficult for them to continue to deceive him as he consistently responded by demonstrating the best of human nature. But it does beg the question I began this with, which is how ridiculous can something fake get before people recognize it as not real?

Apparently the answer is pretty darn ridiculous, but given all the ridiculous things that are real, who can blame him? I’d bet Tim Robbins thought that his satirical mockumentary, Bob Roberts (1992), about an unethical, rich, right-wing candidate running for the U.S. Senate was over the top, but it hardly seems like it now. I imagine War of the Worlds fooled people because up until then everything else on the radio that sounded like a newsflash actually was one, and Ghostwatch because everything they’d seen on the BBC filmed in that style was actually a documentary. With Blair Witch, it was earlier in the age of the internet and lots of people didn’t realize it was possible to create fake websites and IMDB entries or were just less skeptical about the truth of internet content. I think that also on some level, like The X-Files, they wanted to believe.

When it comes to Jury Duty, I think it probably never occurred to Ronald that it was possible to fake all of those things or that anyone would conceive of and execute something that elaborate around him, so no matter how absurd it got, the absurdity of what the cast and crew would have to be doing to make it fake was greater. And really, was he wrong?

~~~

Alex MacFadyen prefers to be a willing participant in the bizarre shenanigans rather than an unwitting test monkey.

Categories: Screen