It was such a long time ago and so mundane, but I remember it as if it were a turning point. I was browsing a boutiquey bookstore, blonde pine shelves stuffed with the kinds of books that end up on self-help short lists. Maybe I was just killing time; maybe I was looking for something I have since forgotten. I don’t know. All I remember is the chill I felt and can still feel as my eyes fell on the title: 20 Things Cancer Patients Want You To Know.

And so: Saw. Saw X in particular. But it was Saw I was thinking of when I was diagnosed with stage III breast cancer not long after finding that book. My treatment included two rounds of chemo–one of these drugs a vesicant my nurses visibly cringed to administer–radiation, and a radical mastectomy, not to mention constant blood draws, x-rays, hot flashes, losing my hair, losing my eyelashes–the ordinary, procedural horrors of trying to stay alive. This was all happening around Halloween, too, which for many years in the aughts was also New Saw Movie Season. I often thought of John Kramer (Tobin Bell)–Jigsaw if you’re nasty–and the bitter truth at the heart of his philosophy: life is a gift that can be taken away at any time, for any reason or no reason at all, and knowing that, really facing it, teaches you to cherish your life. This is the gospel of John Kramer, the good news of Jigsaw, the one thing he wants you to know. And he’s not wrong.

The Jigsaw Killer’s backstory as a terminal cancer patient elevates the first Saw (2004), complicating its sadistic set pieces and ingenious twists with unexpected emotional freight. Jiggy’s grisly traps inspired plenty of imitators in the 2000s, but Kramer’s grotesque life coaching remains the most interesting aspect of the Saw franchise. It’s also a source of conflict, as his many acolytes don’t quite get it, warring with each other like murderous siblings. The films need Kramer’s moral authority, but to get it, they must resort to posthumous revelations and flashbacks, since he straight-up died (and was lavishly autopsied) five, six movies back. But without Kramer, the Saw movies lose their moorings. They become a series of grody escape rooms crossed with Dexter.

And so: Saw X.

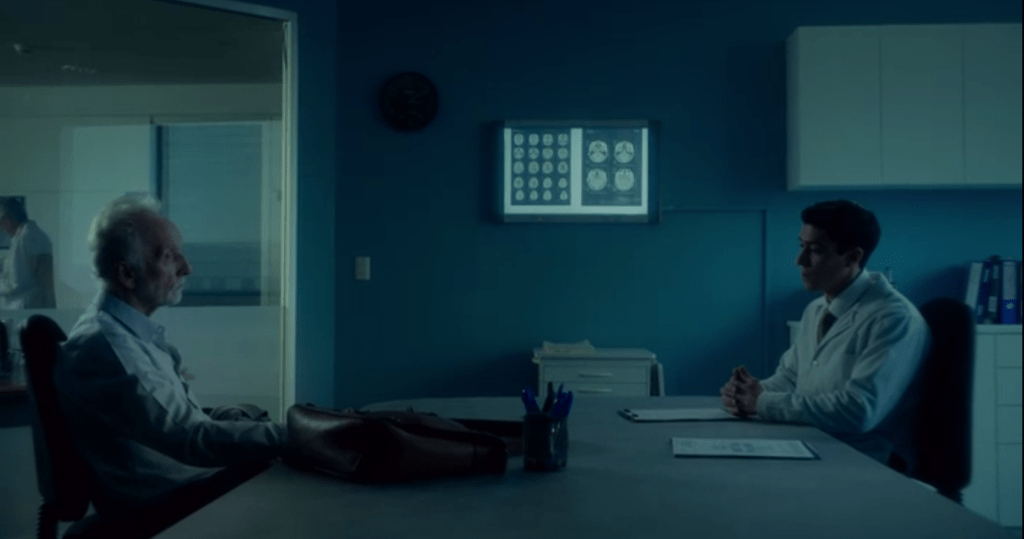

In Saw X, we go back to the beginning, back to the best of the franchise, and that means Kramer alive, if dying, and Jigsaw’s philosophy the subject rather than an excuse. Set between the first movie and the second, Saw X sees Kramer staring down his terminal prognosis. “Your advice to me,” he demands of one doctor, “is to die easy?” There is the traditional torture sequence near the beginning, an amuse bouche lest you think you wandered into the wrong film, but in the end, that is only a fantasy of Kramer’s. It may seem like a cheap fakeout, but there is a narrative point to keeping Kramer a frail, mortal shadow of himself in the first act. The only real torture here is Kramer’s slow submission to the dying of the light, the hopelessness settling over him as cruel as a fixed metal collar–somberly attending a support group for terminal cancer patients, sketching dolefully in the park, lifting the cover page to confront his will.

And then, hope arrives suddenly, a bolt from the blue, when Kramer runs into a man from his support group at a coffee shop. Whaddya know, but this man with stage IV pancreatic cancer is looking phenomenally well, and he confides that it is all thanks to a miraculous new treatment, illegal everywhere, which will send Kramer on a wild chase that ends with his own opportunity to try Dr. Cecilia Pedersen’s experimental cure. Of course he takes it. And, as will be the case with much of this film, it’s heartbreaking, not only because we can relate to Kramer’s physical vulnerability, but because we know what does and doesn’t happen next.

Yes, you’re going to fully empathize with a serial killer, sorry.

The franchise had already struck out at predatory capitalists, most notably the insurance company executives in Saw VI, but even then, the dramatic tension depends on the audience recognizing themselves in the morally dubious insurance people who are just doing their jobs in an unfair system. And with such ambiguous protagonists, Jigsaw looms over the proceedings as judge and executioner, but never quite the villain. Individual disciples have villainous turns, sure, but Kramer himself and his stated principles somehow insulate Jigsaw from being just a villain, and in Saw X, with Kramer’s Jigsaw standing squarely between his successes in the first film and his failures in the third, he pretty much becomes the hero.

Which means someone else is going to be the Big Bad, and the villainy here is cartoonishly thorough. It is a simple thing to hate Cecilia (Synnøve Macody Lund) whose ruse is as elaborate as the most fiendish of Jigsaw’s torture traps and even more fatal, as she chooses dying victims who probably will not even live long enough to realize how they’ve been mislead. She is a Game of Thrones-tier wicked queen. And Kramer’s nobility and empathy is played up in contrast, underlining his avowed hope to rehabilitate his victims, even showing concern for Cecilia’s stooges as they scream and bleed their way through his games. Again his principles are highlighted as the virtuous difference in these films: there are rules, people can win, people can escape, and he does not want them to fail. He doesn’t kill them; they kill themselves. (In his traps, but still.) At times Saw X feels more like an action movie than a horror film, not because of the events depicted, which are still the corroded escape room hijinks the franchise does so well, but the moral clarity of good guys versus bad.

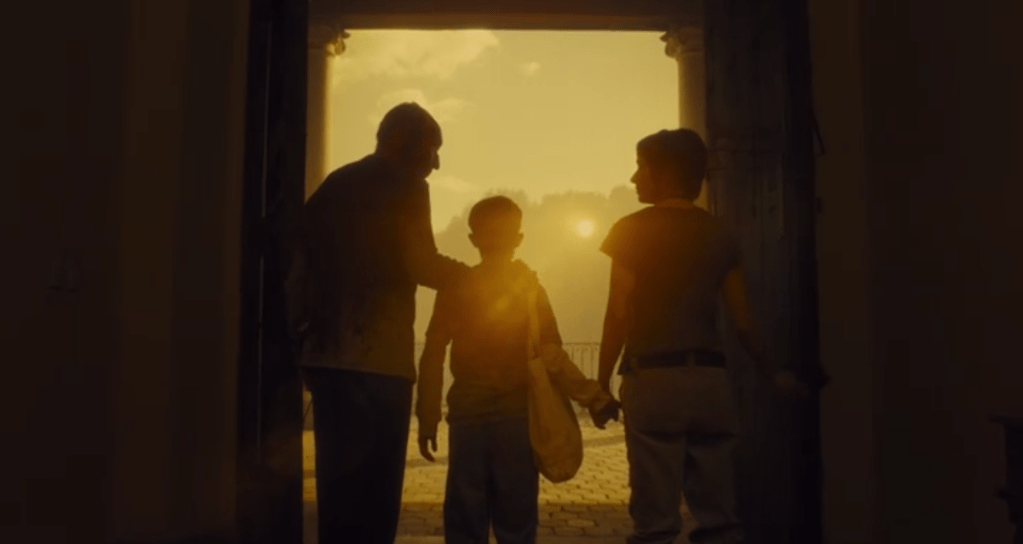

Where Cecilia is a callous exploiter, too, Saw X idealizes Kramer as a rightful patriarch. This begins with his relationship with the son of the groundskeeper at Cecilia’s underground Mexican hospital, Carlos, bonding with kindness without speaking the same language. It is a fragmented mirror of the kind of relationship Kramer might have had with the son he and his ex-wife lost. And once Kramer commits to getting Jiggy with it, the movie brings his disciple Amanda onboard. We last saw her renouncing her mentor’s ideals and indirectly causing both their deaths in Saw III, but here she is the dutiful disciple, anticipating taking over his “work” when he passes on, anxious she is not ready. Amanda’s love for Kramer is highly Problematic, but here–forgiving the fact that they are serial killers–it is the unstinting filial love of a child confronting their parent’s mortality, something the luckiest of us will also one day face. It is a model for how families carry on in the face of death, and much like Amanda’s redemption in the first Saw when she escapes the bear trap Kramer fastened to her face, it’s weirdly wholesome.

I am not sure whether Saw X is the best of the Saw films, whatever best might mean, though it is made with love and careful attention and great intelligence, and I think it might be my favorite, alongside the first. I do think it’s the most likely Saw film to make converts–to the franchise, certainly, to Tobin Bell’s talent likely, and maybe even to the gospel of John Kramer, as this film finally does what every previous Saw has hinted at and played with and lowkey needed, allowing Kramer to be the hero he believes we all deserve. And…he’s not wrong.

~~~

Angela wrote an open letter to other breast cancer sufferers, or maybe just to other mortal humans, on her blog in 2021, and you can read it here.

Categories: Horror

1 reply »