“The first two uses of any technology are sex and war.”

Unknown

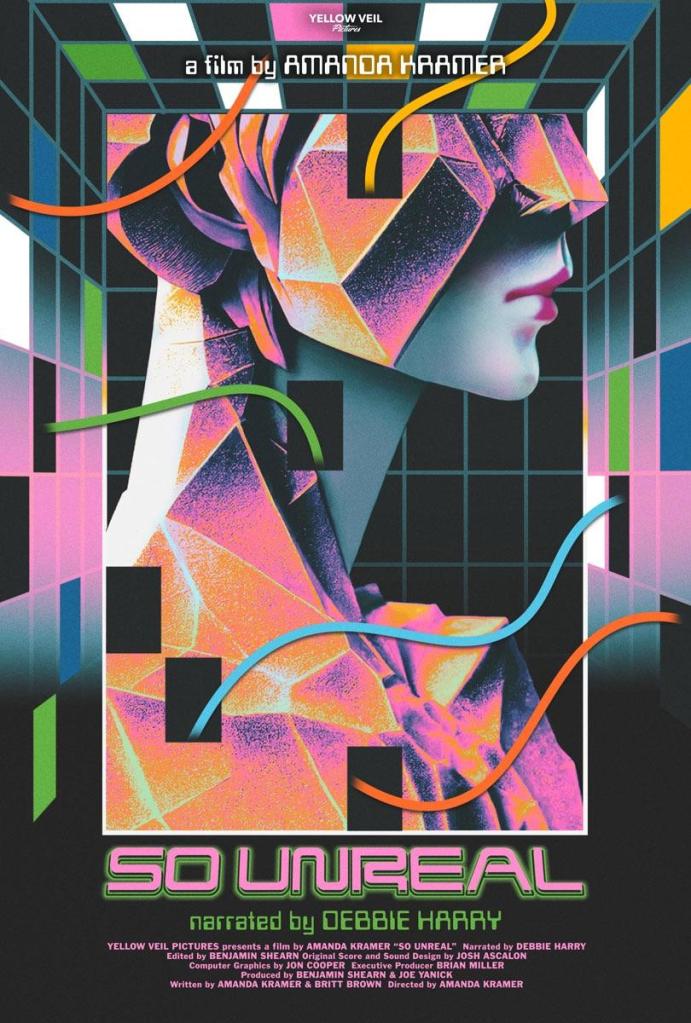

I’m not sure where to properly attribute that quote, but when it’s spoken in the ethereal narration of rock legend and Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry in Amanda Kramer’s new documentary, So Unreal, it has a certain extra gravity behind it. Amanda Kramer has been cultivating a unique kind of horror with both her short and feature-length projects over the past few years. But after 2018’s Ladyworld and last year’s duo of films–the stunning Please Baby Please and the captivating Give Me Pity –a documentary about technology and the internet in the movies was not what I expected from Kramer, though it certainly cultivates horror of a different kind.

Documentary may be the wrong word. So Unreal crosses the line into visual essay often enough that it stays there, blurring the line using Harry’s voice–sounding like a slightly deranged Siri or Alexa–to expound on the depiction of computers and technology in films spanning from the 1960’s through the early 2000’s. So Unreal employs both classics like The Matrix (1999), Tron (1982), The Terminator (1984), Strange Days (1995), and Weird Science (1985) as well as deeper cuts (or, at least, less well-received ones) like Michael Crichton’s Looker (1981) and Arcade (1993) to show the vastly different visions of the future or, in some cases, a technologically-saturated present. Even Mick Jagger’s “Hard Woman” (1985) and Kraftwerk’s pioneering use of computer graphics in music videos are discussed in the multimedia showcase to depict the progression of technology in reflecting our world back at us.

Kramer is tackling a subject so broad and pervasive that it seems impossible for her to run through every possible example, and she doesn’t, but she manages to at least reference most major milestones and high and low points one would expect in this discussion, amounting to nearly 100 films. Rather than going a completionism route, and miring herself in the dry details of circuits and motherboards, Kramer uses Harry’s voice, augmented with reverb, to make the film feel as though it’s being narrated by a sentient computer soothingly walking you, chronologically, from the very earliest depictions of computers in film right to the current day. It’s a remarkably effective tack, and combined with writing that leans towards the poetic, it results in one of the more compelling explorations of a subject that, to me, felt like it had been thoroughly explored.

“Nets are made to catch things, no matter who holds them.”

Amanda Kramer, So Unreal

Fulsome segments are dedicated to The Matrix, Tron, Hackers, eXisTenz (1999), Tetsuo (1989), as well as Electric Dreams (1984) which anticipated the modern smart home, though in a perverse and sinister way. Each successive film or depiction, covered more or less in the order of their release, shows a steady development of both the technology itself, and our understanding of it. That said, some representations of the internet and computers are more predictive than others.

One of the most striking of these deeper dives within a deep dive is a discussion of Michael Crichton’s Looker, which, despite being Crichton’s worst-reviewed project by a wide margin, is shockingly prescient about technology run amok. Looker portends the use of body-scanning and AI to create virtual doubles of models and celebrities, which can then be used for any purpose the creator wishes, without the consent of the model. It’s precisely this technology, now a reality forty-two years later in 2023, that the recent Writers and Screen Actors Guilds strikes find themselves having to fight against, lest their creative works and their very likenesses and identities be co-opted for studio profits without their permission or even their knowledge.

It’s interesting that, over time, the shift in attitude towards technology-as-boogeyman has come with a kind of enlightenment, of sorts. In most of the films discussed in So Unreal–certainly The Matrix, The Terminator, and even Electric Dreams–the boogeyman is the technology itself, usually in the forms of machines becoming sentient and usurping humanity. But it feels like a world, even a decade or two later, that’s steeped in technology like the ubiquity of smartphones, social media and artificial intelligence is rightly more concerned with the people behind them. And why wouldn’t we be? Some of the worst people in the world–studio executives, techbros, and social media barons–are grabbing hold of and trying to exploit and wring profit from these technologies with no thought towards consequences, like they’ve never seen a single one of the films discussed in So Unreal*.

Because what’s at stake here may not be simply more wealth and power to hoard for the wealthiest and least scrupulous among us, though both are certainly up for grabs. When we subcontract our identities to artificial intelligence and the filtered and managed version of ourselves on social media, there’s a cost that comes in the form of self. In most of the films that Kramer discusses in So Unreal there is a kind of campy quality to their production which, to me, feels like a comfort. Films like 1994’s Disclosure (another Crichton) or The Lawnmower Man (1992) which depict early versions of virtual reality still have the hand of a human being steering it, and it shows. Even James Cameron’s weird but steady hand on the first two Terminator films is apparent. Though their focus is the nefarious consequences of computers and machines, they all have a handcrafted element to them, whether in the nature of their visual effects or the forthrightly human feel of the characters and dialogue. Perhaps the one exception is The Matrix, which at times feels like a film that could have come from a sophisticated machine (the jury’s still out on the weird, wonderful, and possibly alien Wachowskis), and that’s kind of the point. It’s an indictment of the coldness of computers, and their lack of emotion and their disdain for humanity as anything but a power source. Even an AI needs inputs.

In our world of 2023, where writers and actors are at the frontlines, literally and figuratively, in the fight against the use of artificial intelligence (though all creative jobs and perhaps most jobs in general will be touched by this, eventually), the containment of this kind of technology often feels like trying to hang one’s coat on a waterfall. There’s an inevitability to the steady march of technology into and over our lives, and like all the innovations we’ve seen in the last century like the internet and social media and basically all of the ideas foretold by the movies discussed in Amanda Kramer’s So Unreal, we will need to grapple with both the benefits and the more insidious implications of them, such as the use of a person’s likeness for any number of nasty and exploitive means without their consent. Kramer, for her part, has picked a side. In a recent interview, she had this to say:

“I think with this idea of what’s real and what’s not real, we’re gonna get to the point where we don’t care, where we’re unconcerned and the unreal will be its own kind of real. I would love to be very, very, very dead when that happens, but I don’t think I will be because of how fast it’s all going.”

Amanda Kramer

Artist advocate group CREDO23, which consists of a steadily-growing group of filmmakers like Justine Bateman, Juliette Lewis, and others are attempting to form a kind of resistance to the onslaught of the profit-for-its-own-sake handlers of artificial intelligence and similar technologies. They are “a collection of film and series professionals that hold filmmaking sacred, and understand their responsibility to preserve the art form.” There is certainly an element of Luddism on the surface of this resistance, but it’s understandable as AI seems to portend an end, or at least a degradation of creativity. If one can simply, as the group asserts, “order up a film that is an amalgamation of the films fed in, [such as] a film starring a Brad Pitt-type, who dances like Fred Astaire, has a Spanish accent, set in the Bahamas, with a Roger Deakins look, and in the style of Martin Scorsese,” will we need any more Pitts, Astaires, Deakinses, or Scorsesae? Does the ‘work’ of art need to be work, or can it simply be taken, wholesale, from the ideation phase and be handed off to generative AI to do the rest? Is there a place for AI in things like music and film restoration, from broken pieces of songs and movies? Amanda Kramer certainly has her beliefs about all of the above, and while So Unreal doesn’t take a strong position for or against the idea of technology itself as antagonist, it seems clear that those who wish to wield it for evil means are the real horror villains, and the real Terminators.

Amanda Kramer’s So Unreal is currently awaiting release from Yellow Veil Pictures. Stay tuned for details!

* or if they have, they are wringing entirely the wrong conclusions from them.

You will be relieved to know that you have been reading the work of Sachin Hingoo, who has been granted a certificate confirming that he is a Certified Human Writer.

Categories: Science-Fiction, Screen