After almost two centuries of reasonably cordial interconnectedness, we seem to be at an inflection point in the relationship between Canada and the United States, for ~reasons~. But as much as Canada has had American culture and history foisted on us, the reverse is rarely true. It has never truly felt as though there’s a reciprocal curiosity about Canadian culture. Maybe if you, reader in America or otherwise outside Canada, have found your gaze turned North in recent weeks and months, it’d be worthwhile to set aside the notion of restrictive tariffs and check out one of our newest and most fascinating cultural exports in the form of Winnipeg filmmaker Matthew Rankin.

Matthew Rankin’s The Twentieth Century (2019) has become one of my favourite movies, Canadian or otherwise. The alternate reality biopic of William Lyon Mackenzie King that gleefully retells history with a hilarious, mischievous, and forthrightly Canadian flourish and a retro-futurist Expressionist aesthetic has become something I throw on when I’m feeling low or – more often lately – particularly patriotic. It’s got a little bit of everything I like; talking animals, a Kids-In-The-Hall-esque absurdist sensibility, a vaporwave-inspired colour palette, and even a light sprinkling of body horror. In these ways it feels like a movie particularly tuned to my sense of humour and overall tastes.

The Twentieth Century zeroes in on the ascent of Canada’s tenth prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King as portrayed by Dan Beirne. Beirne and Rankin’s version of King is tightly-wound and fiercely ambitious, while also reimagining this very real historical figure as a power-hungry and deeply closeted foot fetishist. He feels destined, even entitled, to the position of Prime Minister and will not hesitate to step over anyone to achieve it. In The Twentieth Century’s version of history* King is a perennial member of Canada’s Liberal Party in 1899 and has pitted himself against his arch-nemesis Arthur Meighen (Brent Skagford) and several other candidates in a series of outlandish and fiendishly Canadian trials to become the Prime Minister and serve at the whims of Governer General Muto (the wonderful Sean Cullen). The forthrightly fascist Muto’s intent is to involve Canada in the Boer War in Africa. King is infatuated with Muto’s daughter Ruby (Catherine St-Laurent) who he believes he is destined to marry. At the same time, King also has a strange hypersexualized relationship with his mother (Louis Negin) . This deeply weird and boundary-free sexuality throughout The Twentieth Century that also features a multitude of queer-coded and gender-swapped characters seems to evoke another Canadian export, the work of Bruce LaBruce, whose work is indicative of a kind of aggressive campiness. Rankin’s King is the note-perfect avatar for (and sendup of) the British colonial system while both skewering and celebrating Canadian culture and history. Fascist and grotesque in a multitude of ways, but overtly polite and tucked-in. King (the real one) is mostly considered to be one of the most popular and beloved of our Prime Ministers by virtue of being, well, pretty bland and inoffensive. To then parody him in such extreme fashion that his boot-sniffing fetish at one point ends with a shot of an ejaculating cactus plant, well, if there’s anything that would better get under a fascist’s skin, I’d sure like to see it.

I’ve seen criticisms that The Twentieth Century devolves too far into the realm of the silly, but I hope that if we’re even slightly acquainted and you have some idea of my tastes, that you’ll recognize that this will never be a criticism of anything from me. I can relish and certainly forgive an excess of silliness, all the time, always. And Rankin’s vision of Canada in The Twentieth Century is the precise way in which I like my history presented. Chopped, screwed, and injected with enough laughs and exhilaration that I don’t feel badly that I will probably retain very little of the factual matter (such as it is) that’s presented, like a twisted version of the televised Heritage Minute PSA’s that most Canadians grew up with, right down to the soft-focus. It reminds me of when we’d go to museums or historical sites when I was a kid and they’d have interactive exhibits where you could pretend to pilot a virtual canoe or match the local animal species to their names or habitats in a video game so basic that it lands only slightly above the level of ‘informational shopping mall kiosk’. I was an easily-amused child, and museum curators knew it. Rankin gets it too, and while his absurdist style, stilted dialogue, and particularly Winnepegian flavour to both of his films readily invite comparisons to Guy Maddin – another personal favourite – there’s a whimsy here that Maddin has tried (like in his recent Rumours) but has never quite achieved for me. In fact, the one thing I found myself saying to my movie groupchat after seeing both Maddin’s Rumours and Rankin’s Universal Language at the 2024 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival – coincidentally within hours of one another – that Rankin was doing Maddin better than Maddin himself.

In Universal Language, Rankin turns his eye toward rewriting the present instead. It’s a similarly reality-shifted world in which Canadian (mostly Winnipegan) culture including language, iconography, and architecture, is fused with that of 1980s Tehran. Characters lapse between Persian and French, and the brief glimpse we have of another province, in this case Quebec, shows a kind of hilarious ignorance of any of Canada’s Western provinces (Winnipeg is not, in fact, in Alberta). As a satire, it works particularly well as an allegory for the struggles that the officially-bilingual Winnipeg has had between English and French. Great satire, for me, amplifies the point it’s trying to make to the point of gleeful surrealism and that is precisely what Rankin is playing at. Compared to The Twentieth Century, Universal Language is a softer, more subtle satire. But it’s no less of a clever one.

The film opens on a title card proclaiming the forthcoming to be ““A Presentation of the Winnipeg Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young People.” This is, of course, not a thing in Winnipeg, but the similarly-named Iranian institution that it references was a producer of important Iranian films from the 1970’s onward, like Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven (1998) which was nominated in the Foreign Film category at the Oscars that year. It sets the tone for what could be Universal Language’s elevator pitch; asking “what if the cultures of Tehran and Winnipeg did the Fusion Dance?”In this reality-shifted world, Tim Hortons franchises are beautifully-decorated tea houses complete with samovars and absurdist elements like the cultural idolatry of turkeys, currency emblazoned with the face of Louis Riel (a reference to Iran’s former currency, the rial), and the treatment of Kleenex as a prized commodity add to the dissonance and are the fuel for many of Rankin’s best jokes.

Schoolchild Omid (Sobhan Javadi) claims that his glasses have been stolen by one of the turkeys that roam free in town and are spoken of in tea houses and among the wealthy with reverence. His unhinged, overbearing French teacher (Mani Soleymanlou) decides that school will not continue until the specs are located. His classmates Negin and Nazgol (Rojina Esmaeili and Saba Vahedyousefi) find a 500-Riel bill frozen in ice and get the idea to use these newfound riches to replace Omid’s glasses. At the same time, Rankin himself plays Matthew, a man leaving his crushing bureaucratic job in Quebec to visit his ailing mother in Winnipeg. Upon his arrival, he learns that local tour guide Massoud (Pirouz Nemati) has supplanted him as his mother’s son and caregiver.

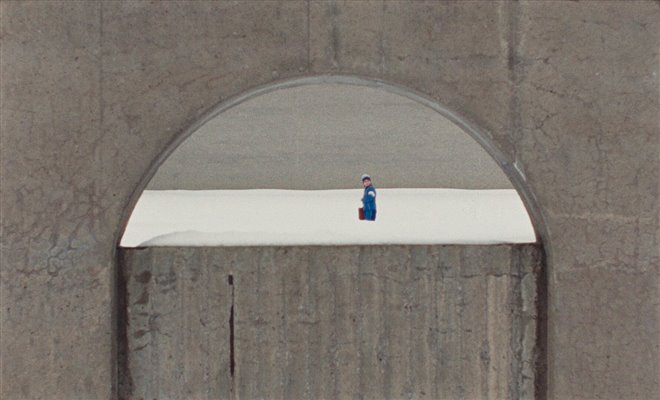

Visually the film is not as immediately striking as The Twentieth Century’s even more video game-like scenes and setups, but Universal Language‘s juxtaposition of Canadian iconography and architecture with Iranian elements and the Farsi language is more than enough of a visual cue that Rankin’s world is not exactly our own even if they require a little more of a deep look and a moment to parse them. You know that’s a Tim Hortons logo. And coming from a similarly brutalist-centric Canadian city myself, cinematographer Isabelle Stachtchenko perfectly captures the particular way in which big blocks of oppressive concrete can seem elegant. Maybe not so fun to actually live in, but when the light hits it just the right way, not bad to look at.

When I watch both of Matthew Rankin’s feature films, they feel like a peek into a version of Canada that feels familiar to me, even if the details are anything but. Turkeys do not, in fact, roam free causing chaos in most places in Canada. Canadian Geese sure do, though. Both The Twentieth Century and Universal Language just get Canada and what it means to be Canadian on a cellular level. Tightly-wound sometimes and deeply weird, but ultimately charming and fun in our way. And Rankin’s work is so filled with beautiful and perplexing curiosities so compelling that I would happy to watch a whole movie about nearly any of the side characters in his stories. Ninety minutes about the life of the guy working in Universal Language’s Kleenex dispensary? A medical docudrama in the style of ‘The Pitt‘ set in The Twentieth Century‘s Hospital For Defective Children? Yes please! It might be a Canada that’s broken in hilarious ways and crushingly disappointing sometimes, but in whatever language and whatever century, it’s our Canada.

Starting in April, Sachin Hingoo will be subject to a 10% reciprocal tariff.

*It’s not my intention to bore you with corrections to Rankin’s warped history. It would probably be a shorter and far more manageable thing to list off what is accurate, but that seems almost equally boring and I will thank you, reader, to join me here in this post-facts world that, unfortunately, we all must share.

Categories: Screen