Exhuma is an occult thriller about a group of experts who come together to resolve the haunting of a family in Los Angeles, Seoul and near the border of North Korea. I enjoy it immensely. It stars Choi Min-sik of Oldboy (2003); I Saw The Devil (2010), and, Heaven: To The Land of Happiness (2022), Kim Go-eun from Little Women (2022) and Monster (2014) and Yoo Hai-jin from A Taxi Driver (2017); Veteran (2015); and, A King & The Clown (2005). I suggest seeing the movie before reading this piece. CW for Exhuma: Possibly live fish death; threatened baby; threatened rooster; significant vomiting; the inexorable horror of imperial history.

~~~

The past is very present in writer/director Jang Jae-hyun’s Exhuma (South Korea, 2024). There is familial and imperial history reaching back to World War II and even further. And if there are not precisely demons in the film, well, there are things that are close enough.* Shaman Lee Hwa-rim (Kim Go-eun) and her partner Bong Gil (Lee Do-hyun) have been summoned to Los Angeles by the extremely wealthy Park family to discover the source of an occult affliction. New family patriarch Park Ji-yong’s infant son is hospitalized. Testing has determined there is nothing physiologically wrong with the child, but since birth, the only time the baby stops crying is when he is sedated. Ji-yong (Kim Jae-chul) tells Hwa-rim and Bong Gil that his wife has suffered two miscarriages for indeterminate reasons and that his brother died in a psychiatric ward. Ji-yong’s father (Jung Sang-cheol) appears to suffer some form of dementia. Ji-yong says, “When I close my eyes, I hear screaming.” After her initial investigation, Hwa-rim informs Ji-yong that she believes his deceased grandfather is haunting the Park family. Trapped in his grave and angry, the spirit of Park Geun-hyun (Jeon Jin-ki) is targeting his family’s first born sons. Hwa-rim calls in help from Geomancer/ Pungsu-Jiri** expert Kim Sang-duk (Choi Min-sik) and Funeral Director Ko Young-gyuen (Yoo Hai-jin) about exhuming and relocating Park Geun-hyun’s body. The film’s Korean title is Pamyo, the word people in the film cry out before beginning an exhumation, and it means the exhumation and relocation of a grave.

The Park family keeps much from the experts they have called in, including who their grandfather is, why Park Ji-yong wants him cremated casket and all, and why he is not buried in the Park family plot but is instead buried alone on a mountain on the border with North Korea. The grave’s area is host to a skulk of foxes—tricksters and shape-changers—that haunt an ancient tree. Kim asks who recommended the plot for the burial and is told a Buddhist monk named Gisune did. Gisune is a peculiar name for a monk and to me, at least, it sounds a bit reminiscent of “kitsune.” It is especially strange that a wealthy and high status servant of the country like Park Geun-hyun has been buried in a spot that Kim declares “vile.”

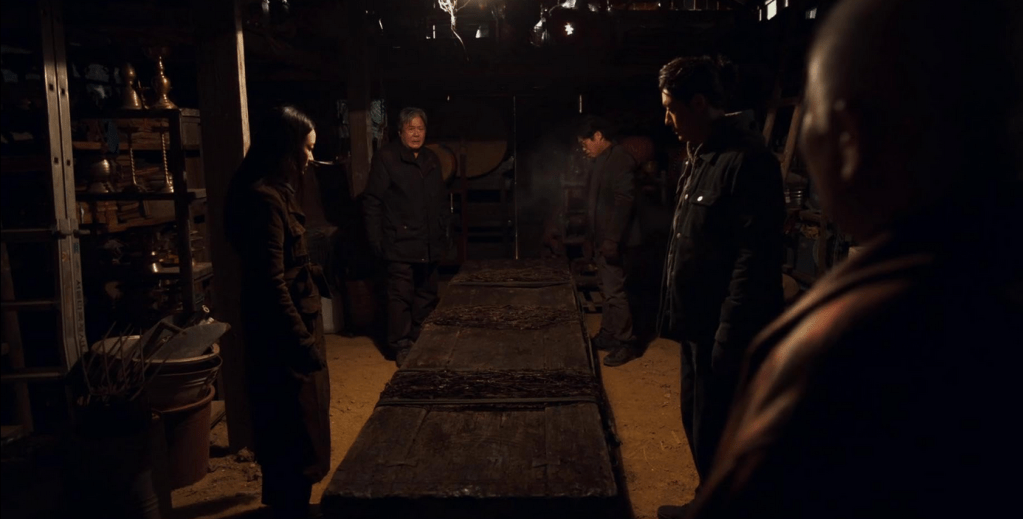

“No human being should be buried here,” Sang-duk tells his colleagues privately. The spot is so cursed that Sang-duk at first refuses to exhume the grave. He considers it far too dangerous. But Ji-yong appeals to him as a father and by doubling the offered fee. Besides Hwa-rim has a plan. Sure, it’s one that has never been tried before, but Sang-duk needs the money for his daughter’s upcoming wedding. Ultimately, the trio agree on a plan to remove the casket while simultaneously distracting the angry ghost and protecting the gravediggers as they work. And so we get a wonderful scene—created with the help of actual Korean shamans— where Hwa-rim and Bong Gil perform the ritual while Funeral Director Ko orchestrates the removal of the coffin.

When the team digs up Park Geun-hyun, they literally dig up the past. The Park family has been keeping a secret beyond the fact that their grandfather has been angry about his grave site for most of their lives.

The plan goes well, until it doesn’t. After the coffin’s removal, a gravedigger sees and kills something he shouldn’t have. There is a heavy rain that prevents the immediate cremation of the remains and casket. And Ji-yong’s aunt takes the opportunity to urge that her father’s remains be relocated in the Park family plot instead of cremated. The coffin is taken to a local morgue and sealed for the night. But, of course, the angry ghost cannot stay restrained in the coffin forever. Grave robbers have been after the coffin for decades because of rumors that it contains treasure. When he does escape, Park Geun-hyun is cruel and relentless. He murders his daughter-in-law as she tangos along to Dancing With The Stars. He menaces his great-grandson in the hospital. And he tricks Ji-yong using one of my favorite devices in contemporary horror—a medium like a phone becomes a medium for spirits, too.

The Park family’s secret is revealed in one of the most unsettling and frightening possession sequences I have seen.*** Kim Jae-chul’s transformation from terrified Ji-yong to terrifyingly possessed Ji-yong is remarkable. There are no fangs or glowing eyes. There is no levitation or crab-walking. There is simply a change in posture and stance as his body becomes ramrod straight, he extends his arm in a seig heil, and begins a fervid speech exhorting the men of Korea to join with Imperial Japan in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Kim performs a subtle yet complete transformation from frightened and desperate father to a fascist filled with maniacal fervor. I almost regret sharing the moment here, but it was so shocking, so unexpected to me. In subsequent viewings, the revelation was still unsettling, but I think this transformation is something best experienced without expecting it or evaluating it against my experience. In a film that is so careful in its focus on physical effects and real world location shooting rather than digital effects, this approach to the possession is one of director Jang Jae-hyun’s best choices. I love creatures and monsters, but there is something unnerving about seeing someone simply become someone else.

Park Geun-hyun had been a high-ranking collaborator on a Japanese-controlled committee governing occupied Korea during World War II. And Park attacks his son, his daughter-in-law, his grandson and his infant great-grandson not only because he has been forgotten and left in a vile place, but also because he is an unutterably awful person and was before he died. In this moment of possession, Park Ji-yong is possessed by the past, by collaboration, by fascism, and by his grandfather’s unforgivable choice to collude with the atrocities enacted against his country and people. Presenting the past—in particular the fascist past—as malevolence that can possess people, especially young men, in the present is intriguing. It tracks with many people who experience friends and family members seemingly becoming different people as they are drawn into xenophobia, ethnic and religious nationalism, authoritarianism and fascism. And Ji-yong’s subsequent death is an illustration of how a past often considered best forgotten, damages and can kill us in the present and future.

In another movie, exorcising the ghost would be the end of the film. But in Exhuma, there is more to it. The team discovers there is another occult mystery when one of the gravediggers falls sick and Sang-duk returns to examine the grave. Park Geun-hyun’s burial site was not accidental or thoughtless. He was not buried in a bad place by an incompetent or unethical priest making a buck from a wealthy family. He was not buried in a vile spot as punishment for his collaboration. But he was buried in that location for a reason. Like so many other toadies, collaborators and purged cadre, Park Geun-hyun was discarded in a way most useful to his superiors, regardless of its impact on him. Sang-duk and Young-gyeun discover another coffin buried beneath Park’s—one that Park’s was intended to conceal. It’s 7-feet in length, wrapped in wire and buried vertically. And if you have seen Ricky Lau’s horror comedy, Mr. Vampire (Hong Kong, 1985), you know that is no good.**** Even without having seen Mr. Vampire you probably know that is no good. That enormous casket contained a Japanese spirit, a samurai general (Kim Min-joon) who died at the Battle of Sekigahara and 300 years later was turned into a guardian of an occult device meant to paralyze Korea itself by the Japanese monk Gisune, nicknamed, “The Fox.”

Park Geun-hyun becomes a demon by betraying his own people and embracing fascism and its fantasy of purity and power through self-abnegation. To me, he is more of a monster than the enormous samurai of Exhuma‘s second half. The samurai general is indeed terrifying and blindly violent, a true burning sword of malevolence. But he did not actively choose to be. He died over 400 years ago. He was disinterred during the Japanese occupation of Korea, and was made into the guardian of a curse and a weapon of occult warfare. He might’ve been awful, but what was done to him was horrifying, too, and not his choice. Park Geun-hyun, though, chooses his monstrosity. He chooses to become a collaborator, a fascist and to embrace Imperial Japan and its plans for Greater East Asia. And he is rewarded not with glory, but with a vile burial plot to conceal another terrible thing. It’s all part of an occult assault on Korea that only Sang-duk, Hwa-rim, Bong Gil, and Young-gyuen can stop. Given how satisfying it was to me, I cannot imagine how satisfying it was to a Korean audience to see all of them join forces to defeat the demonic specter of fascist imperialism.

I loved the group of specialists working together and their cunning plans based in their specializations. And I love an occult thriller —especially one that is, unlike, say, the novels of Dennis Wheatley, anti-imperial and anti-colonial. Exhuma is a gorgeous and satisfying movie with just enough humor and humane moments to take the edge off the cruel history the film presents. I would love if it were a series where in each episode Kim, Lee, and Ko get together—with Bong Gil, of course—to solve a new occult mysteries. And I appreciated that each of the three experts represent a different element of Korean religious life. Aside from Hwa-rim as a shaman and Sang-duk’s geomancy/Pungsu-Jiri and dashes of Confucianism, Funeral Director Ko Young-gyeun is a Christian who is very willing to help his colleagues with their ritual needs. After all, it seems, these particular occult problems are not a matter for Jesus beyond encouraging words from Ecclesiastes. And there is even a poor Buddhist monk at a dilapidated rural temple who helps with information, a shed, and hot noodles near the cursed gravesite. Unlike so many occult horror and occult thriller films, these occult afflictions aren’t exorcised by one religious tradition, but by many.

I also appreciated the little nods to other films about evil spirits and their bad intentions and attention. The most obvious being probably Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (Japan, 1965). As in Kwaidan‘s “Hoichi the Earless” segment, there is a troublesome ghost samurai and, like Hoichi, Exhuma‘s investigators write Buddhist sutras on themselves to protect themselves from it.

All the performances are excellent. It’s one of the best ensemble films I’ve seen in a long while. It is a pleasure to see Choi Min-sik, Kim Go-eun and Yoo Hai-jin work together. They have fantastic chemistry and camaraderie. And each time I have watched Exhuma, I see something in one of the performances I hadn’t noticed before. This last time, watching with the Gutter’s own Alex MacFadyen, I appreciated the complexity of Lee Do-hyun’s Bong Gil, who at first seems fully fledged, but a side character—until he’s not. I am also enjoying Choi Min-sik’s current era of playing tired, grumpy old men in this and Heaven: To The Land Of Happiness (South Korea, 2022). There’s a wonderful moment when Sang-duk realizes he can’t just give up because he has his daughter’s wedding to attend. Sang-duk becomes the family patriarch that Grandfather Park was not and could not be. After earlier crabbing about how his daughter is pregnant before she is married, that she is marrying a German, and that his baby will have blue eyes, Sang-duk welcomes his son-in-law and his son-in-law’s family into his family. And he acknowledges his colleagues, bringing them into the family and expanding the idea of both family and the family patriarch. Sang-duk might be crabby, but understands that change and growth are fundamental to life.

I only wish that that Exhuma had spun off a series—even a miniseries. I want to spend more time with these characters. And the idea of a group of experts on geomancy, shamanism and funeral direction joining forces to solve occult mysteries every week sounds good to me.

*I considered using the names for the paranormal creatures in the film, but I think it might reveal too much of the mystery. Even though I do definitely talk about it and this is another suggestion to go see Exhuma before you read this piece. It’s streaming now. You can watch it for free on Kanopy and support your library.

**Very loosely, a Korean kind of Feng Shui.

***I say this knowing that unfortunately saying something like this creates expectations. Look, we all have different feelings. Never expect to feel what someone else does. If you go in trying to “objectively” evaluate this possession as “frightening” against other things that have frightened you and then it doesn’t, it is not a failure of the film. It’s not a failure at all. It’s a difference between you and me.

****Never, ever good. And there is, perhaps, more of a reference to Mr. Vampire with a malevolent spirit bursting out of the coffin. Though it is a stretch. A vertical coffin is problematic Feng Shui regardless. And while Exhuma has comedic moments, Exhuma is not a horror comedy.

~~~

Spirits are tempted by tasty foods and gossip—just like Carol Borden, who is, nonetheless a perfectly normal human being!

I received a screener for Exhuma as part of my coverage of the Overlook Film Festival 2024. And have watched few times on Kanopy, too. This piece expands on a review I wrote at Monstrous Industry.

2 replies »