Burnt Offerings (1976) opens, as so many of my favorite scary movies do, with our relatable heroes driving winding roads deep–into the country, into the woods, into the mountains. Into deep space, for that matter, if you want to extend the metaphor to its outermost limit. It doesn’t really matter where, except that it’s far from home, far from help. (Cue Mrs. Dudley.) And yet, the demons which really prove to be the heroes’ undoing are almost always something they’re carrying with them. Or, as in the case here, something they want so much, the wanting becomes a thing in itself.

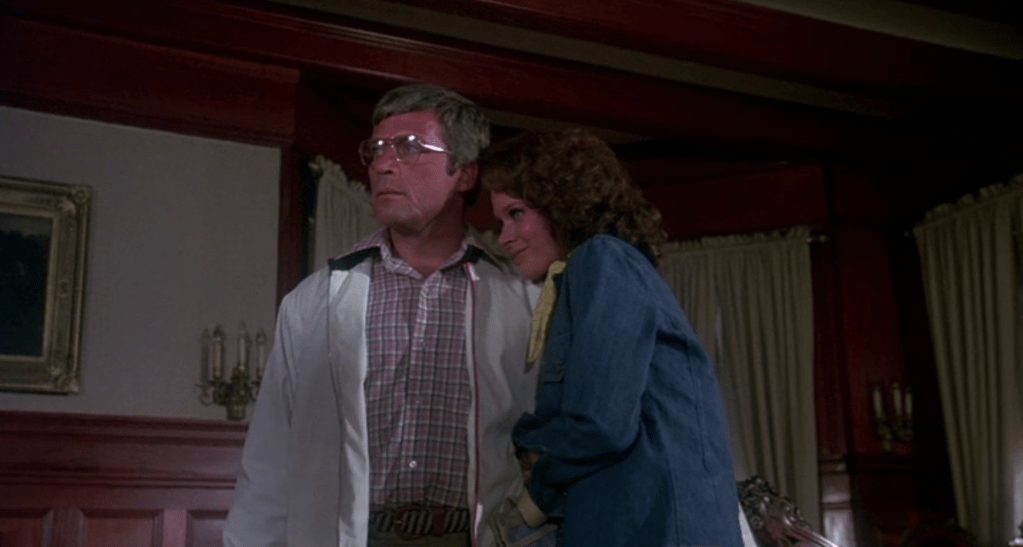

In Burnt Offerings, those unlucky heroes are the Rolf family–schoolteacher dad Ben (Oliver Reed), mom Marian (Karen Black), and their 12-year-old son Davey (Lee Montgomery), and the place far from home is a palatial neoclassical estate advertised as a summer rental. Fun fact: the California mansion that played the house in Burnt Offerings has since played other houses in other things, among them Phantasm’s Morningside mortuary. And it is available for rentals! You can get married there, kids!

From the outset, Ben is skeptical. Numberless rooms could lie behind the great house’s doric columns. There’s a greenhouse, a pool. How could they afford to rent such a place? There must be some mistake. But Marian dismisses his misgivings, instead focusing not just on how beautiful the place is, but also how neglected. As impressive and capacious as it is, it does need work. The doors are peeling paint in ugly patches; mirrors are broken, plants are dying, glass is dirty. It’s such a waste, Marian anguishes. The house needs someone. …Maybe the house needs them?

As a matter of fact…

After running into the delightfully earthy handyman (Dub Taylor), the Rolfs meet the house’s owners, an enigmatic, somewhat queer-coded brother and sister, Roz (Eileen Heckart) and Arnold Allardyce (Burgess Meredith). The Allardyces are well-bred and congenial and not business-like about this business at all. Instead, they appeal to Marian’s emotional investment in the house, and it is less that they are looking for renters than hoping for caretakers. As such, their ask for the place is $900–not nothing certainly, even now, but a shockingly low number for such a huge property for an entire summer. The catch–though the Allardyces deny it is one–is that their mother will be remaining on the property. Their mother who never ventures out of her room. As if that’s a reassuring thing. All they ask is that the Rolfs bring her meals to her. That’s all. Unquestioning Marian is ready to start schlepping tea trays immediately, so that only Ben (and the audience) are looking at Burgess Meredith wax rhapsodic about the immortality of the house and thinking mom must be either Mrs. Bates or something worse.

He’s not wrong. Writer-director Dan Curtis, beloved mastermind of TV’s Dark Shadows, The Night Stalker, Trilogy of Terror, and so much more, is not at all coy about what’s going on in this, his only theatrical release film outside the Dark Shadows series, based on a novel he didn’t even really like. Part of what Curtis disliked about Robert Marasco’s original story was apparently its ambiguity. Curtis is not here for that, and the decisions he makes emphasize the house’s cruel intentions. Journeys end in lovers meeting, and horror movies end with victims in pools of themselves. And so, in these opening scenes, we get a subtle, but definite demonstration of the true nature of the compact being drawn up between these two families when Arnold Allardyce spies Davey playing on his own in the yard, and the boy falls and hurts himself. It would be instinctive for anyone seeing Davey seize his bloodied knee to wince or to coo, but there’s no flinch, no sympathy from the older man at all. Quite the opposite; he relishes it. Have you seen Burgess Meredith relish something? It’s quite clear. Not only that, but he deliberately distracts Davey’s parents so that he doesn’t get help too quickly. For Allardyce, the boy’s pain is a good thing. His suffering should be prolonged. And when the family leaves, without looking, Arnold tells the handyman that the plant he’s about to throw away is living again. And of course he’s right.

On the road home and back in their depressing New York apartment, Ben and Marian will argue about taking the Allardyces up on the offer, but what happens next is manifest. On July 1, the family, plus Ben’s Aunt Elizabeth (Bette Davis) pull up to the mansion to discover an all-but-empty house waiting for them. The Rolfs have found their summer place. The Allardyces have found their burnt offerings.

It is a capitalist critique, of course. There are no ghosts in the house, but there is beauty, and that beauty is replenished with the lives of the people paying to stay there. It is trickle-down diabolics. That’s the other thing that’s plain about it, in book and movie. Marian Rolf is a good person, a faithful wife and a devoted mother, but she also likes nice things. Actually, she loves nice things, she worries about them, she emotionally invests in them, and it is probably a credit to Karen Black’s likability that she remains as credible as she does for as long as she does. To some extent it bothers me that the wife without a job is the weak link for the insidious forces in the house, that her whims outweigh her husband’s nagging reservations, but then, call it a feminist capitalist critique, too. This is the nature of feminine influence in a time when a woman couldn’t have her own bank account.*

Marian’s American Dream-patterned avarice aside, the part of the movie most people will take with them into their own bad dreams is the chauffeur. Not a song by Duran Duran but just as spooky, this chauffeur is a recurrent delusion (or is he) of Ben’s, inspired by a memory from his mother’s funeral when he was a boy.

There was a dream—the playback of an image really—which had been recurring, whenever he was on the verge of illness, ever since his childhood. The dream itself was symptom of illness, as valid as an ache or a queasy feeling or a fever. The details were always the same: the throbbing first, like a heartbeat, which became the sound of motor idling; then the limousine; then, behind the tinted glass, the vague figure of the chauffeur…. What’s death? —he’d have to say a black limousine with its motor idling and a chauffeur waiting behind the tinted glass.

Burnt Offerings, Robert Marasco

For a schoolteacher supporting his small family, worried about money, worried about getting his doctorate, trying to give his wife the vacation she dearly wished, it is telling that the grim specter of death remembered from his boyhood is driving a limo.

Credit must be paid, however, to the truly iconic creepiness of Anthony James’s leering face. The score, the shot framing, Oliver Reed dissolving in front of it, the whole thing.

Stephen King loves this movie, too, and you can tell because The Shining hits a lot of the same elements and even the same plot beats–comic relief handyman, a house feeding off the people living there, the slow-but-steady possession of one of the family so that you can never be certain who’s at home behind the lights of their eyes. In Burnt Offerings, Marian’s aspiration is the weak link. As soon as they arrive, Marian pores over Mrs. Allardyce’s collection of portraits the way Jack Torrence buries himself in the secret history of the Overlook, and the way she spurns sex except when it takes Ben’s mind off the house is a lot like Jack seducing Wendy into forgetting her apprehensions in The Shining. Of course we have a kid to endanger, too, as Ben forgets himself roughhousing in the pool, and here it’s a midnight gas leak instead of a wasp’s nest that attacks the boy in his sleep. King’s book is a good deal more layered than any movie could be though, and so the main throughline of Curtis’s story reads so much more simply: do not aspire to these beautiful things, working man. You are chattel. Curtis cuts away any prelude in Marasco’s novel that might give its essential capitalist critique or its characters further dimension, as King does with cycles of child abuse, domestic violence, and alcoholism in The Shining. Such focus does not make Burnt Offerings less effective though, particularly in the medium. It is an editorial decision, perhaps encouraged by a background in TV and working with such blunt TV veterans as Richard Matheson. This uncomplicated narrative may not be satisfying beyond the depth of a fable, but I don’t think it needs to be. Oliver Reed smashing a Coors can against his own face in white-knuckled terror is more than enough for me.

What really chills me about watching Burnt Offerings or thinking about the novel in 2023 is how the Rolfs are at once sympathetic and relatable in the relative position of have-nots in a society that treasures its haves above all, and yet…they’re going on a two-month vacation. On a teacher’s salary. Even though we understand they are getting the Allardyce estate for a huge savings, adjusted for inflation, that $900 has the purchasing power of over $6000 today. And honestly, I would have trouble coming up with 1973 dollars. The capitalist critique is baked in to Burnt Offerings. It’s genuinely horrifying that it also lays bare the vulnerability of a middle class that is so much richer than most Americans ever will be.

Burnt Offerings (1976) is currently streaming on Tubi and Pluto TV.

*The novel was published in 1973. American women got the unassailable right to open their own bank account via the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974.

~~~

Angela thinks Oliver Reed would have been an amazing Jack Torrence.

Categories: Horror

An *amazing* Jack Torrance! Yes. Sigh.

LikeLiked by 1 person