“I was the colour red in a world full of black and white. I had the whole world in my hands.”

Windham Rotunda (“Bray Wyatt”)

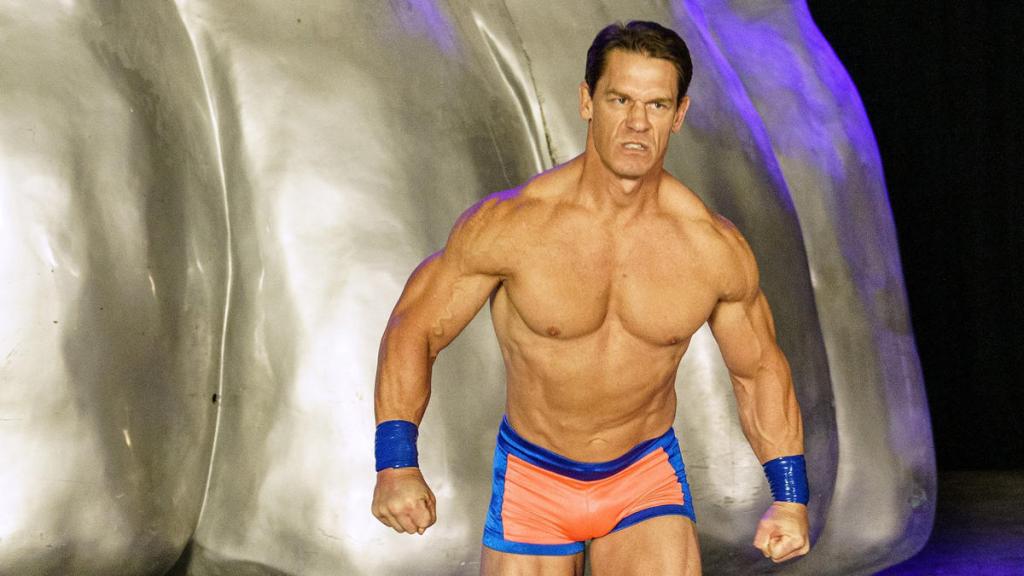

John Cena emerges from the entranceway as he normally does. But nothing about this is normal. That worst-possible reaction, the reaction that every wrestler dreads the most, is no reaction at all, and that’s precisely what Cena receives as he steps out onto the stage. Gesturing and playing to fans that aren’t there, his too-big, crowd-pleasing grin looks maniacal as his music blares, reverberating in the closed set without the noise of thousands of fans to complement it. But that won’t be the strangest thing either he or we, in the viewing audience at home, will experience in the next 20 minutes. Not by a long shot.

I don’t watch WWE that much these days, for various reasons. Besides the problematic (to say the least) nature and decisions of its upper management, it’s a product that feels increasingly homogenized, sanitized, and willfully ignorant* of its own history, and in doing so it has lost a lot of the appeal that it had for me as a kid and young adult. But with the tragic and untimely death of one of its biggest stars, Bray Wyatt (real name Windham Rotunda) a few weeks ago, it got me thinking of the last time I was truly enthralled with the so-called Worldwide Leader In Sports Entertainment.

In April of 2020, as with all of us, pro wrestling was in something of a state due to a then-new and even more mysterious pandemic. The annual two-night WrestleMania event wasn’t able to be held in public (despite WWE’s and, depending on who you ask, Ron DeSantis’ best efforts) due to lockdowns, and was filmed in the WWE Performance Centre training facility, which was repurposed as a closed set with no fans in attendance. Wrestling doesn’t work very well in this environment, and the traditional matches on that card, despite involving some of my favourite talents, felt incredibly flat without the push-pull of a lively crowd steering and amplifying the action. Still, I watched, curious how the ‘show must go on’ ethos of a company that has powered through all sorts of real-world circumstances – many that it probably shouldn’t have – to deliver a wrestling card by hook or crook, would weather this storm.

Two matches in the combined lineup, one per night of WrestleMania, stood out though. Filmed outside the set and with a more ‘cinematic’ approach, matches between AJ Styles and The Undertaker, dubbed a “Boneyard Match”, and one between Wyatt and the perennial conquering hero, John Cena called a “Firefly Funhouse Match” showed that WWE was willing to adapt its tried-and-true format and do something truly subversive.

Well, sort of. Matches that take place outside the confines of a ring, that have a multi-camera and a highly-produced and edited quality to them have happened throughout wrestling history, both in the WWE and in other promotions. There’s a certain magic that can be conjured when wrestlers leave that environment, transposing these larger-than-life figures for whom being driven headfirst into concrete is just another day at the office into, in at least one case, an actual office. We’ve had Booker T facing off against Stone Cold Steve Austin in a grocery store, Sting and Vampiro mixing it up in a graveyard, and Matt Hardy’s various matches on the Hardy Compound (including one with Bray) to name only a few. But there’s something different about the Firefly Funhouse match. A self-awareness and willingness to look inward at the creative decisions that brought these two performers into conflict with one another.

The screen ripples and distorts. The video cuts from Cena to the sickly-sweet tones of Bray Wyatt’s ‘Firefly Funhouse’. This is a gimmick that Bray has been using for a few months now, and is best described as a twisted Mr Rogers show ostensibly aimed at young children. There are puppets, bright colours, and a twinge of malicious energy bubbling just beneath. Bray, wholesome-looking and sweater-clad, introduces the show, jovially letting us know that John Cena will be facing his most dangerous enemy in this match – himself. And so begins an almost stream-of-consciousness spiraling journey through Cena’s career, shepherded by Bray as both host and antagonist to Cena, like a twisted Jacob Marley from A Christmas Carol. It is one of the most avant-garde, genuinely scary, and high-concept “matches” the WWE, and I daresay any wrestling promotion, has ever produced.

We begin in 2002, where Cena debuted in a segment featuring real-life Olympian Kurt Angle. Angle has issued an open challenge for anyone in the locker room to face him. Out comes John Cena, and for those that say that Cena’s most popular gimmicks were generic, this version of Cena says “hold my beer.” He’s decked out in nondescript trunks and boots, and despite his impressive physique, looks like the default figure in a create-a-wrestler suite in a video game, before you do any customization to it. The segment switches between actual video of this segment from 2002, and current Cena and Bray (who takes over the Angle role) re-creating the event note-for-note. Bray is antagonizing Cena, and taunts and goads the future superstar into punching him. In the real segment, Cena knocked Angle out, but here he finds nothing but air.

In this segment, and the ones to follow, Cena will be confronted by his own insecurities and shortcomings, many personified by a ‘how are they getting away with this’ depiction of WWE’s slimeball (onscreen and in real life) CEO, Vince McMahon. In this stage of Cena’s career, he was very nearly fired from WWE outright due to a lack of character or personality. He was basically that generic wrestler that could be mistaken for a dozen others, until goaded by McMahon to display ‘ruthless aggression’. It’s a nebulous term which WWE immediately copyrighted and, again rewriting history, used as a blanket term for this era of the company.

At this point, Bray pulls Cena into an 80’s-style world, where the WWE is even more of a place where big muscles (achieved, usually, via chemical means) are the shortcut to stardom. Cena and Bray are portrayed as tag partners here, cutting a promo with the manic energy that typified that era of wrestling. Wyatt is wearing workout gear while Cena is dubbed ‘Johnny Largemeat’ and frantically pumps a set of dumbbells in a way that clearly communicates that he’s not in control of this ride. John Cena is Not OK.

Cena’s next stop is the persona that saved his career. Referencing the popularity of Eminem, Cena became ‘The Doctor of Thuganomics’, a white rapper who cut vicious battle rap-style promos on his opponents before matches. Here, Cena is locked into this persona, out of control once again. He can only speak in rhymes, and his rap bars aren’t landing. As John goes for lower and lower verbal blows, Bray looks genuinely hurt by barbs about his weight. Wyatt calls out Cena as a bully, who has had unlimited chances in WWE. It’s a fourth-wall-breaking moment, and it feels as though we’re seeing Bray become more sympathetic before our eyes. He begins to look sad for John as he teleports around and behind Cena, who becomes more and more frustrated.

We’re coming to the end of this ride but, before we do, Cena will have to confront what he did to Bray. At Wrestlemania 30, six years prior, Cena and Bray faced off in their first encounter. In that match, it seemed as though Cena, who was on his way out of the company and moving onto Hollywood, would take a loss to Wyatt, whose star was on the rise. Instead, Cena went over Bray cleanly, and stifled a lot of Wyatt’s momentum, and some might say he never got it back. It’s at this point that we realize what Wyatt’s plan was all along. Not just to beat Cena, but to make him realize that WWE’s perennial babyface character, one who the fans had begged to turn heel, was actually the bad guy all along. Bray draws a direct line from Cena, unwilling to embrace this idea, to Hulk Hogan, whose heel turn into Hollywood Hogan in 1996 breathed new life into that character and, it can be argued, into wrestling as a cultural entity. Even in this form, Cena tries to mount offense against Bray, only to find that Bray has been replaced by Huskus The Pig, one of Bray’s Firefly Funhouse puppets and a manifestation of Bray’s insecurities around his own body issues.

Cena, left without a gimmick and rendered completely powerless, finds himself completely at the mercy of Bray. Wyatt, for his part, has become more powerful than ever, and takes on his most wretched form – The Fiend. He pins Cena in quick fashion, with Wyatt’s Firefly Funhouse persona counting to three. Cena vanishes, having battled his own demons, and lost. The traditional bell signifying the end of a match is nowhere to be found.

Bray’s career would have its ups and downs after that, and the Fiend persona fell prey to WWE’s penchant for overdoing things and overexposing their characters and stories. In one of his last promos from October of last year, Wyatt lays himself bare, talking seemingly from the heart about his struggles out of the ring. It’s unfortunately stopped short and interrupted by some superfluous WWE razzle-dazzle, but it’s the moments before that I choose to remember as the final curtain on the career of someone whose creativity and unique mind we only got the briefest glimpse of before his untimely death. The Firefly Funhouse Match was, for me, the last time I really felt that WWE was capable of something truly against-the-grain, where instead of choosing the safest creative option, it greenlit something akin to true horror, with real catharsis at the end for both characters. It’s not wrestling, per se, in the purest sense, but on that night it didn’t have to be. It, like Windham Rotunda, was more than enough.

* At best. At times it’s hostile to it and openly revisionist when it doesn’t fit their chosen narrative.

Sachin Hingoo is saddened by the death of Bray Wyatt, who passed away suddenly on August 25, 2023 at the too-young age of 36. He was a special, standout talent and creative mind.

Bravo fam – this was a great read and tribute

LikeLiked by 1 person