There is a conventional wisdom that says works of horror are at heart cautionary tales and that once you tear up their planks, all you will find beating beneath is a pulpy warning to the curious, a brutal morality tale leftover from darkest days and firelit nights. This usually isn’t entirely untrue, but it is almost always insufficient.

Not with Pumpkinhead (1987) though!

Born at the crossroads of the rise in 80s supernatural horror and the decline in 80s slashers, Pumpkinhead has fewer ideas than you would typically find in either. But that’s not a bad thing. Special effects legend Stan Winston’s directorial debut may be a messy business in all its shortcomings, but in its brilliance, Pumpkinhead is singular and pure and, as it happens, super simple, anchored by Winstona’s gorgeous visual vocabulary and Lance Henriksen’s heart-wrenching performance as a bereaved dad come face-to-face with his worst self. There is a razor-sharp masterpiece in Pumpkinhead, buried in the flavorless nougat of crappy movie. But spite is Pumpkinhead’s soul and its warrant, and the message when you get down to its vicious heart is a homily against the poison of revenge, however justified.

Sometimes such a simple story comes with a truckload of plot. This is Pumpkinhead’s way, and it takes its time getting to the point. Importantly, we do get a brief taste of the Pumpkin King’s wrath in the opening, a foreshadowing flashback to Ed Harley’s (Lance Henriksen) childhood, but this is just an appetizer. Back in the present, a group of teenagers on vacation arrive at the tiny country store that widower Harley runs with the help of his adorable ray of light moppet son Billy and their equally adorable pup Gypsy. Harley loves his little boy, and his little boy loves his daddy, and while Mama is dead and gone, no other cloud darkens their horizon, unless you count Harley suddenly remembering Pumpkinhead’s silhouette as the teens’ dirt bikes roar in the distance. But anyway. Billy and his daddy. The sheer Hallmark Channel purity of it! Clearly someone must die.

And they do. Ed leaves Billy to mind the store* as he rushes off on an errand, Gypsy starts barking at the teens riding their dirt bikes in the surrounding hills, and Billy tries to round the dog up. The gradual, inevitable churn of all these elements–world’s best son, adorable dog, absent dad, darn teenagers–toward a fateful accident is mad-den-ning, Winston dawdles those puppet strings with extreme leisure. The only good part is that the dog ends up okay.

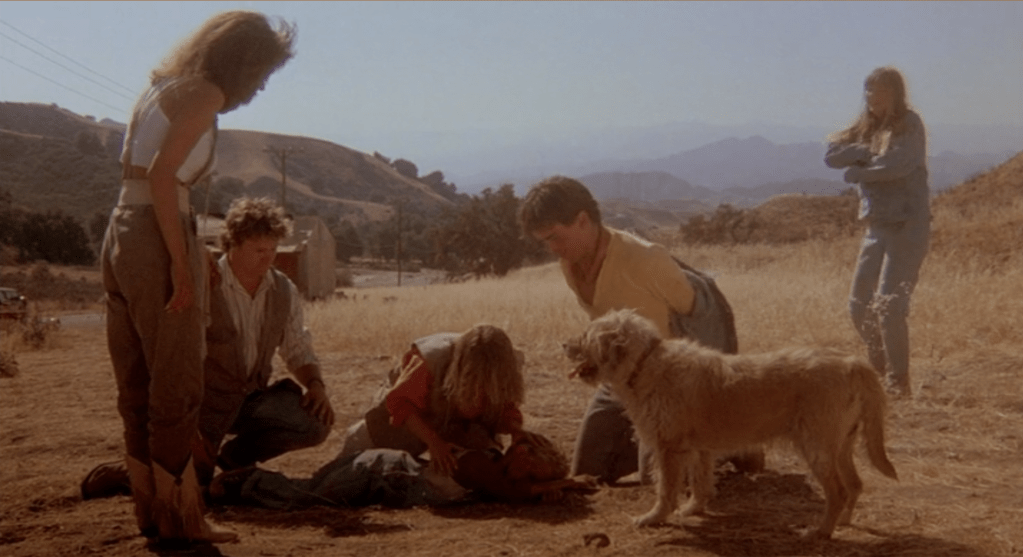

There’s no visible blood or wounds–probably for sensitivity reasons, though still a glaring omission for the FX master–but Billy takes a dirt bike to the face about as well as one would expect. He’s not dead on the spot though, and the group is soon at odds about what to do and where to get help. The group takes off to seek a doctor or a phone or something, while one stays behind to wait for Billy’s dad. Plot twist: the teen who struck Billy doesn’t actually want to get help and holds the others hostage at gunpoint, because he’s afraid of the consequences. [tents fingers] Oh, he has no idea.

We welcome consequences though, because consequences are when all this movie-like product gets peeled away, and ah-ha! Here is the stuff, the art, the joy, the beauty, the horror.

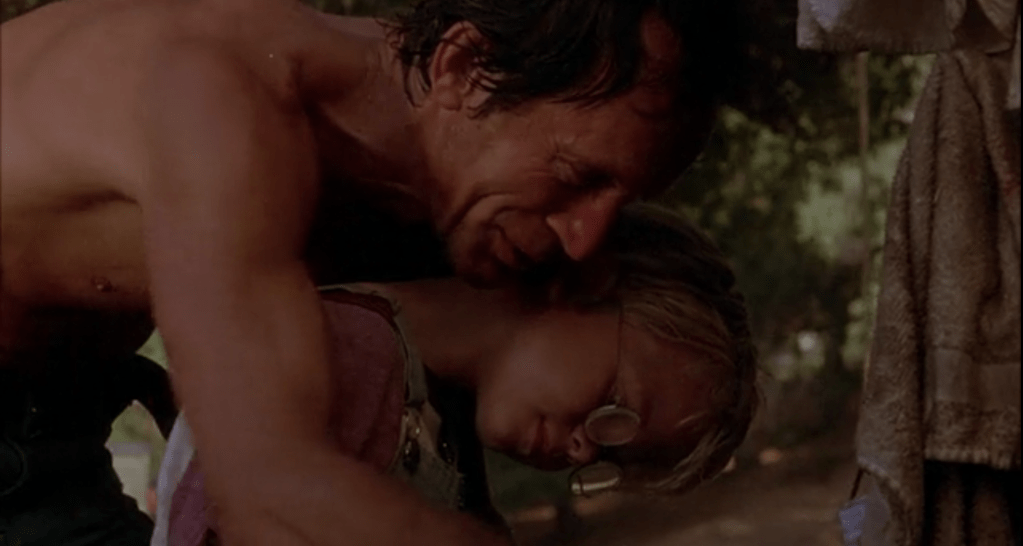

When Harley discovers what has happened, there’s no questions, no demands, no outcry. Harley skips ahead to the part where he’s furious and grief-stricken. Wordlessly, he whisks his son from the nonplussed stranger, not to a doctor, who might be as helpless as anyone to save Billy, but home. In the context of the film, this is hard to understand, and I would not have minded if the movie had taken a minute to show me why. Not knowing makes what comes next feel contrived, as Billy dies quietly in his father’s arms. But then Harley leaves his home again, cradling the blanket-wrapped body of his son in his arms, and we are on to consequence time. Last chance to run pee; now it’s getting good.

The film totally changes gears once Harley is on his mission for vengeance. What was the sun-soaked, samey first reel of any 80s slasher with a cast of indistinguishable idle white teens falls away into pure folk horror. As seen in such films as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes, Deliverance, et al, Pumpkinhead’s sons of the soil harbor secrets and monsters both, and Winston’s direction finds all the vivid, mist-shrouded beauty in Harley’s grim trip up the mountain on the trail of the legendary, dreaded witch Haggis (Florence Schauffler). Haggis can’t raise the dead, she cackles, and she makes a point of telling Harley that she can’t help him, meaning Harley’s son, twice. When Harley doesn’t leave, she goads him to ask what he really wants. Revenge. And Haggis tells Harley what he is seeking comes with a powerful price.

Here is some free advice. If you go to a mountain witch, and she tells you that what you’re asking has a powerful price, be a little curious about what that price is.

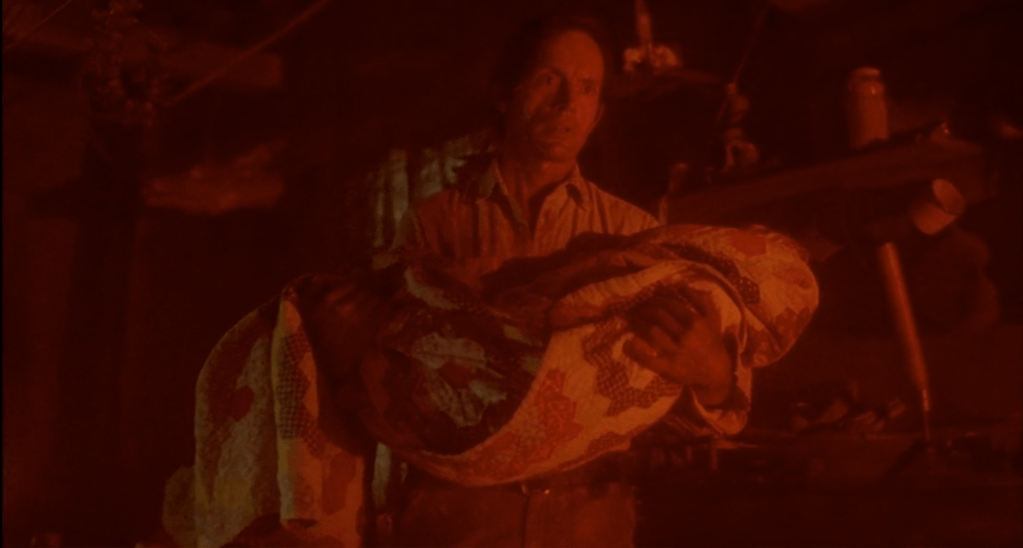

Harley is not curious. Harley is not afraid. Harley is probably still halfway in shock, and Henriksen is kind of playing him that way, too. But at the witch’s direction, he goes up into a graveyard/pumpkin patch and disinters a monster, bringing him back to the witch in his arms the same way he carried his dead son. Sidebar, but I cannot say enough good things about how textured and rooted Lance Henriksen’s performance is throughout–hell, how good his accent is, even if they made him wear Bubba teeth–but he particularly rules in these scenes, conveying disgust, exhaustion, loathing, despair, and finally a perfect Gothic heroine swoon as Haggis prepares Pumpkinhead’s resurrection with a generous helping of Harley’s blood.

The exchange of Harley’s son for undead squashy champion could not be simpler or more plain or more painfully poignant, like a woodcut illustration from a fairytale. There is only one relationship that really matters in Pumpkinhead, and it isn’t the relationship between Ed Harley and his son, not really. It is the bond between the man and the monster, the grief and the anger, Harley and Pumpkinhead himself.

What follows qualifies Pumpkinhead as a slasher, although it brings the lighting and the wind machine to keep it in the otherworldly, weird territory of slashers like Hellraiser and Phantasm, rather than a nice orderly Halloween. Along the way, there are a few glimpses back into the more ordinary film it began as, but once Pumpkinhead is unleashed, the fabulist, eldritch tone is unleashed with him. Teenagers are picked off in gruesome ways, but all the dramatic tension lies in the struggle between Pumpkinhead and Harley, as Harley experiences a Pumpkinhead POV of every kill and every kill brings the monster closer to subsuming the man.

When Harley demands help from Haggis, she mocks him instead.

Haggis: It’s what you wanted.

Ed Harley: No! Not like this! Not like this! I see it! This is wrong!

Haggis: Nothing I can do. It’s gotta run its course now. What did ya think, it’d be easy? Neat and clean and painless? You’re a fool.

What did Harley expect? When he was only as old as his son, he saw what Pumpkinhead was capable of, and he heard the terror of a man–maybe an innocent man?–it was hunting. He was haunted by it. He had a strange intrusive memory of it as soon as he saw those teenagers. Or maybe it was a premonition? A more A24 take on the material might convict him of looking for an excuse to summon the monster of his childhood. It is true he tells Haggis the kids abandoned Billy, but not all of them had, had they? Is he lying to her or to himself?

This is where the simplicity of the film works in favor of its moral, as Harley tries to stop Pumpkinhead all by himself, and he finds that, just as Haggis told him, what he has done will have to run its course. If you look at the film as two parts–the setup with the teenagers and Harley’s retribution–only one of these can stand on its own. The teenagers’ plot is a vestigial limb. As important as Billy is to Harley, we could have started the movie with the boy’s death and no prelude, because it is really is all about Harley facing the consequences of his anger, his actions, his quest for revenge, and once begun, there’s no reflection on how wronged his little boy was. How much we sympathize with Harley in the moment of losing his child is forgotten as soon as he plants that shovel by Pumpkinhead’s pumpkin head. This isn’t a story about the consequences of dumb kids having a terrible accident; this is a harsh sermon about the price of seeking vengeance, and even the dumb kids’ eviscerations are only in service to one man’s willful self-damnation.

* It was the 80s. Even good parents did this kind of thing.

~~~

Angela thinks Pumpkinhead is actually kind of cute.

Categories: Horror