Tender Dracula, or Confessions of a Blood Drinker (1974), also known as La Grande Trouille (The Big Scare), might really only exist for two reasons: Peter Cushing and boobs. …I guess that’s three reasons.

Sorry. But if that joke made you groan, you’re probably going to need more than Peter Cushing or boobs to get you through Pierre Grunstein’s absurd erotic comedy, because that is the key of Benny Hill to which this whole film resonates. And yet, while the piece is undoubtedly amateurish, underfunded, and underimagined, a certain je ne sais quoi persists, something transcendent that cannot be fully owed either to the female beauty on display or Peter Cushing absolutely crushing it like the professional he is, dammit. Cartoonish and slapdash and hectic as Tender Dracula is, it’s interesting. To quote Benoit Blanc, “It makes no damn sense. Compels me though.”

The premise of the film is a good one though: legendary horror star MacGregor (Cushing) no longer wants to star in horror films and demands a new romance vehicle instead. And so the producer of MacGregor’s hit films tasks two of his writers, Boris and Alfred (Stephane Shandor, Bernard Menez), to kill off the star of their hit series “The Growing Pains of Daphne” and replace him with MacGregor–but also to make their show a horror show. What was a conflict-rich starting point is already self-contradictory and awkward, but slapstick irrationality is where Tender Dracula lives. A Scooby-Doo chase through the title cards and this whole setup with the producer goes a long way to establishing its psychedelic vibe, and with the vibe at least, it shall be consistent.

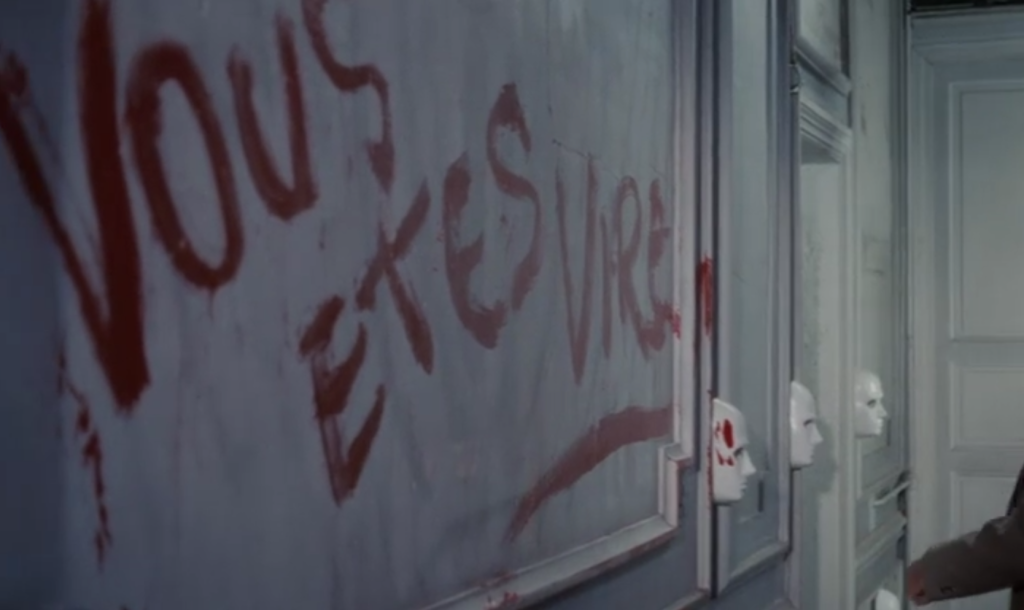

I must pause a moment, too, simply to bask in the nameless producer’s office–Doctor Who round things on the walls, red and purple soft furnishings, Peter Cushing posters everywhere–as the producer stamps and yells and demands, backed up by a robotic female voice he summons with a button on his desk. “You’re fired!” he tells the writers. The writers leap to their feet. “Sit down!” the robot lady cries. The writers cower back into their chairs. It isn’t funny, but it is fun, and I want that office for myself so, so much.

Okay, back to the movie. With two beautiful young starlets in tow, Marie and Madeleine, (Miou-Miou, Nathalie Courval), Boris and Alfred visit MacGregor’s home castle for a weekend of spooky inspo and a secret campaign to make the star come back to horror films. And it shouldn’t be so difficult. When they arrive, MacGregor seems like he’s living in one of his old movies as it is. The castle is fully broken battlements and spiderwebs, and it’s minded by a hulking mute manservant, Abelard (Percival Russel), and Abelard’s ex-wife, who is also MacGregor’s current wife, Mabel (Alida Valli), called Heloise because MacGregor considers Mabel too prosaic a name for his one true love.

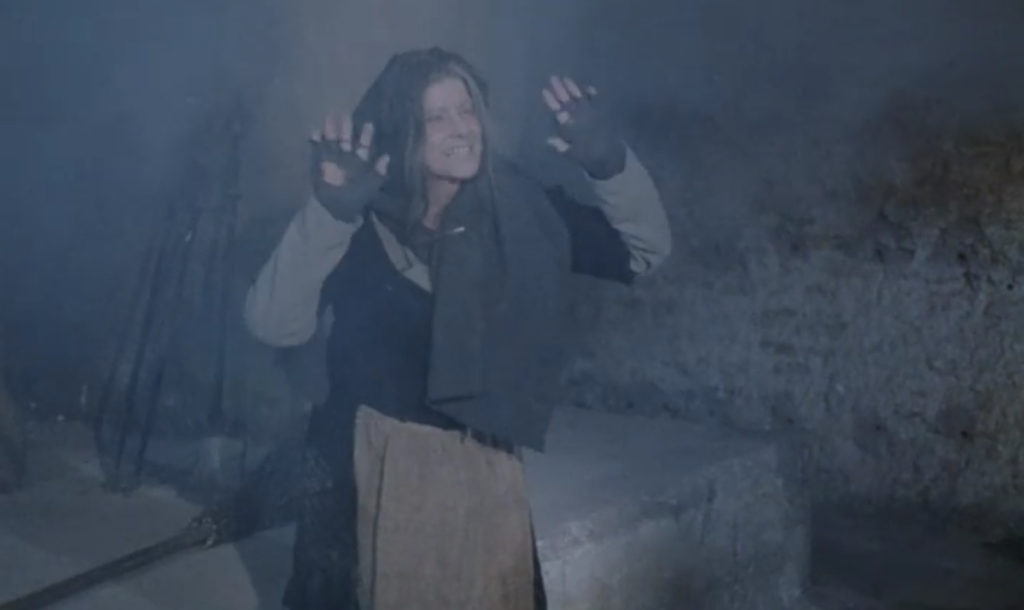

Her name isn’t the only thing that will change; Heloise de-ages and swaps hair colors and styles throughout the film, but at first, she is a witch straight from a 14th century woodcut, shawled and gray before she disappears, cackling, in a puff of smoke. MacGregor himself is no less fit for Spirit Halloween, greeting his guests in a cheap Lugosi Dracula costume at the top of the stairs. In later scenes, he will even have his hair blacked into the Lugosi widow’s peak, his mouth a thin red line of lipstick. Horror is over, MacGregor will insist again and again, but that doesn’t mean he is changing his wardrobe.

There are shenanigans from this point. Boris–once an aspiring makeup man in his native Russia and inspired by stumbling on MacGregor’s theatrical makeups–pretends to shoot himself, and there are other faux maimings and murders as MacGregor’s castle yields its own spookhouse surprises like disembodied legs to chase you and taps running blood. Having discarded their luggage after a car accident on the way (MacGregor reminding them it would not have been very romantic to have arrived in a car with their luggage anyway), the girls dress themselves in gauzy drapes and very theatrical Grecian face paint, while the guys do their best with a trunk of costumes. Poor cuckolded Abelard plays a waltz after dinner, and new lovers dance, MacGregor and Heloise dance, and as much as the writers want to convince MacGregor his talents lie in horror, MacGregor muses endlessly on his unswerving dedication to the art of love. Eventually there is tame torture and there are tame orgies, but nothing is sexy, nothing is frightening, nothing is funny. It is, however, all somehow lovely.

There are beautiful moments in this film, both in terms of its cinematography and their evocation. So much of Tender Dracula is cheap and obvious, from the amateurish smear of Hammer red blood to suggest a cut without a wound to the way Cushing is obliged to thunder most un-Peter Cushingly at MacGregor’s guests for want of a boom mic, that when the beautiful transcendent business happens, it’s a shock. The horizon of MacGregor’s estate at sunset; a candlelit waltz; the blue mist wreathing the backlit horror actor. And sometimes the beauty lies in a weird kinetic moment of audacity, like the bizarre scene in the producer’s office or the swelling atonal Kraftwerkian flourishes of the score.

The most stubborn beauty in the piece, the easiest to celebrate, lies in the relationship between MacGregor and Heloise. Silly jokes about Abelard aside, the couple relate to each other not just as a committed couple or passionate lovers, but as mythic, eternal beings ever captured in the purity of first and total love and capable of making that transient state last. Given the strangeness of MacGregor’s castle, it would be easy to infer he really is a vampire, and she a witch, or something very close to it, as Heloise dreamily recalls MacGregor pursuing her naked through the woods. And as the film goes on, MacGregor is clearly more invested in playing Cupid for his guests than finding a new starring role for himself. The only stars he is interested in are in his lady wife’s eyes. “I am free. I have a right to be gentle. Because of you, I created for the first time,” MacGregor tells Mabel/Heloise. “I created your smile, your companionship, your soft hands, your tenderness, that which is in your heart. You gave me romance.”

There is something in Tender Dracula of 1977’s Hausu, which brought together its own group of one-note characters to a cursed house that is too bizarre to be simply funny or scary and ends up slyly telling its own love story, albeit a tragic one. But Tender Dracula really reminds me of the same year’s Madhouse, which put Cushing together with Vincent Price, Price starring as Paul Toombes, a former monster movie star whose signature role, Dr. Death, had been created by Peter Cushing’s character, Paul’s old friend Herbert Flay. Madhouse used reels of Price’s real AIP oeuvre to stand in as Dr. Death clips, padding the runtime with classics like The Pit and the Pendulum and The Raven, and while Tender Dracula doesn’t go so far as to try to pawn off Peter Cushing in The Gorgon as MacGregor’s work, the many Hammer-style posters in the producer’s office and photographs of Cushing in his memory book will remind the audience that he ain’t faking being a famous monster movie star. I would not be surprised if the Dracula costume Cushing wears as MacGregor were the same one he wears as Herbert in Madhouse either. But more than that–and this will sound more fault-finding than I feel–there’s something about the almost absent-minded, ad-hoc carelessness of both films that unifies them, a confidence that whatever weirdness gets us from a scene with Peter Cushing to another scene with Peter Cushing…or maybe an orgy, okay…it’s going to all work out.

And it does.

Tender Dracula is in some ways a perfect Cultural Gutter film–not because it is good or because it is so bad it’s good, but because within its low budget, low genre walls, a stubborn species of high art thrives in lowbrow trappings, like a dandelion poking through concrete, and some will still call it a weed. Of course this is not a great work of craft, and yet, give it time, its irrefutable inspiration slips in, particularly in MacGregor’s romantic musings and the chemistry between Cushing and Alida Valli, which go a long way to rationalizing what Cushing might have found interesting in Tender Dracula, presumably apart from his fee. You’ll never find Tender Dracula among the list of Cushing’s best works and are quite likely to find it placed with his worst, and yet I can’t dismiss it or dislike it, and I think that if anyone managed to watch it more than once, they would feel the same. This movie may only exist for two three reasons, but chances are that’s not why you’ll remember it.

Tender Dracula is currently streaming on IndiePix Unlimited.

~~~

Angela could really go for one of Abelard’s Bloody Marys right now.

Categories: Screen