A slasher movie from the killer’s point of view: it sounds like a joke, a Robot Chicken sketch, a few stray lines of off the cuff Joe Bob Briggs before he’s interrupted by the movie he’s hosting. Did you ever wonder during the slasher movie, what is the killer doing in-between all the actual slashing? I mean, after he finishes his arts and crafts time, posing his victims and heavy breathing under the girls’ cabin window? He’s got the time. Is he doing some serial killer self-care? Limbering up? Does a psycho killer shit in the woods?

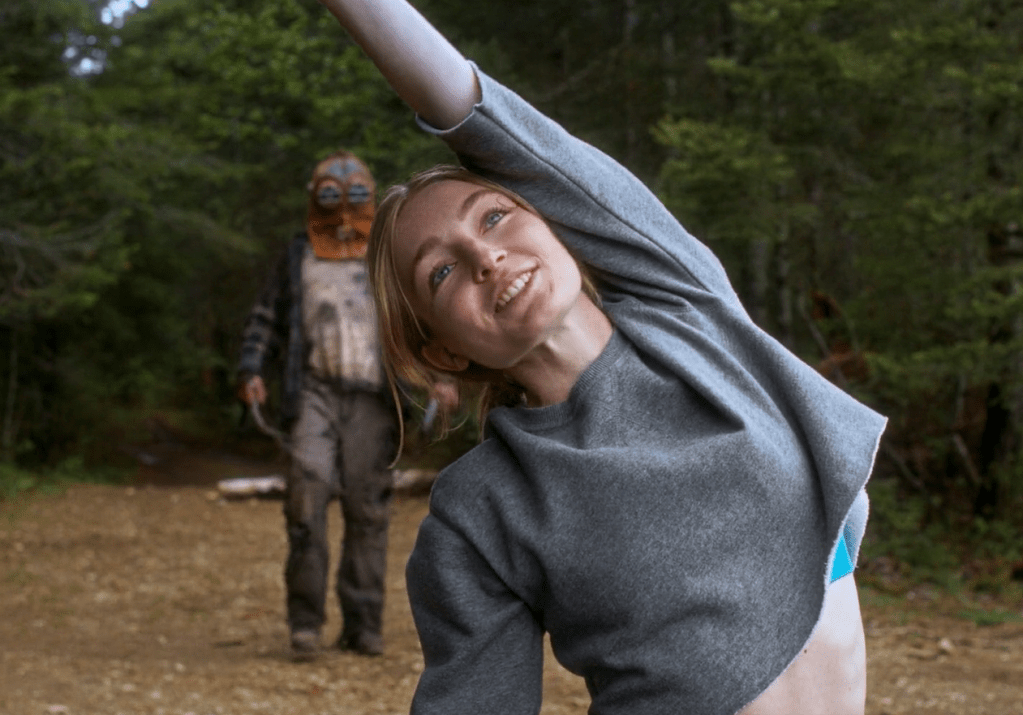

But this is the unspoken premise of writer-director Chris Nash’s In a Violent Nature, and for the majority of the film, that is what it delivers: not quite the behind-the-mask killer POV from the opening to Halloween (1978), but nevertheless a view to a kill that identifies the masked killer as the main character for once. If there is any snarkiness in its formulation, in execution, it is deadly earnest, following its masked killer as dispassionately as a nature documentary. For a film that never strays far from tropes and cliches–that openly relies on its tropes and cliches–so much of In a Violent Nature should be easy to digest, no matter whose eyes we are looking through or whether you enjoy this kind of film or not. What makes it brilliant, what makes it ritual rather than routine, is less its focus on the killer’s POV than how using that particular POV weaponizes expectation against its audience. Far from simplifying identification with its masked killer Johnny, the premise becomes the stage for In a Violent Nature’s masterclass in dread. Wait for it. You ain’t gonna miss a thing.

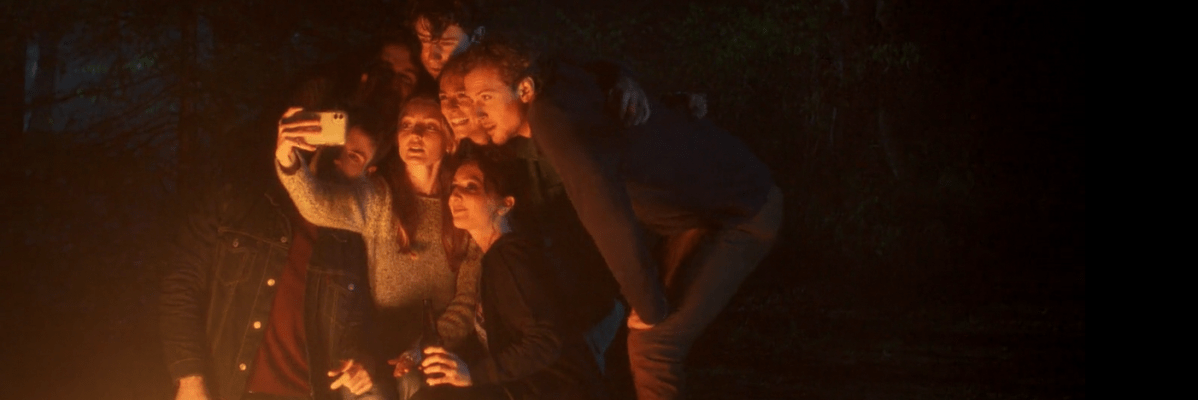

The story of In a Violent Nature is obviously, purposefully derivative. Its elements are pretty common across fifty years of slasher history, but even the least familiar with the genre should still easily link it to the most commercially-successful slasher series of the 1980s, Friday the 13th. Like Friday the 13th, In a Violent Nature begins in woodsy seclusion, with friends (well, “friends” anyway) discovering a locket hanging in a collapsed fire tower near their campsite. We can hear the guys allude to “The White Pines Slaughter,” which already feels like the campfire retelling of Jason Voorhees’ drowning or his mom’s death. Before the guys leave, one of them steals the locket, which proves to be the trigger for undead killer Johnny (Ry Barret) rising. Resurrection takes a minute, so the guys are gone by the time Johnny is up from his dirt nap, but that’s okay. He’s got time.

All the dialogue and interaction that we hear from the guys visiting the fire tower, by the way, is overheard. No faces, and yet we know them already: the two romantic rivals circling each other with innuendo, plus the hard-up one who is a little creepy and a little bit of an outsider even in his friend group. There will be a couple direct moments of exposition–one via Johnny’s flashback to his father giving him his mom’s necklace, and another where Johnny floats unseen in the woods at the edge of the kids’ campfire, listening to the full retelling of the White Pines Slaughter–but most of the film is simply overheard. As someone who loves piecing together horrible backstories from scattered log files and bloody fragments in horror games, it’s a lot of fun. And there is something darkly comic in the way fierce arguments between characters, infidelity, seduction, rejection all take their course while death comes marching steadily toward them, in earshot and closer with every step. It’s even more amusing as Johnny’s doomed victims realize their friends are disappearing, and the film we’ve been trained to expect unspools just offscreen in car horns and screams and frantic shouted plans, although it’s also not funny at all.

From the outset then, we only have oblique knowledge of the victims stationed along the track of Johnny’s inexorable rough justice. Inexorable takes time though, and I am sure there will be those who dismiss the movie as a walking simulator. I mean, Johnny does get his steps in, that’s for sure, and you have to be paying attention, I think, for the frequent cuts showing the changing angle of the sun as Johnny trudges, trudges, trudges through the woods at a good, brisk Kane Hodder pace to work on your nerves. I will make no apologies for suggesting people watch the movie they’re watching instead of scrolling TikTok between the screamy bits though, and the pacing of the film is very good, no pun intended, in that we are given a nice tone-setting early kill to establish exactly what kind of menace is stalking in the general direction of his mother’s necklace. It is, however, in the immortal words of Tom Petty, the waiting that is the hardest part.

This waiting does not come with hold music though. There is no score in this film, not even one, so no Harry Manfredini hooks to tell you when to tense up and when it’s safe, and this contributes to the relentlessness of it, the inevitable tightening of dread as you watch and you wait and Johnny kills and you wait again. To not be shepherded by a score or jabbed by a tension hook is weird. Even the news and reality shows have emotional music cues. Instead you are free to focus on the SERIAL KILLER STALKING ASMR FOR STUDYING birdsong and leaves crunching as Johnny hunts his victims, making it all the more startling when a car horn or a gunshot or a scream rips through the horizon. Small sounds cannot go unnoticed–the hopeless sob when a paralyzed victim realizes what the engine Johnny just started up means, the abrupt, choked-off bleat of another victim dragged under the water, the decisive thunk as Johnny buries his hand axe in a tree trunk so he’s free to go get more hands on. It’s not just the quiet moments either. No one watching this will ever forget how loud the woods can be at night.

Let’s talk about those kills though. One of my own personal pet peeves about slashers in general is that people die too fast. They do! Take any 80s slasher. Whump, stab, you dead. That’s just not how things really work, and how things really work is so much worse. But hey, In a Violent Nature is here to address that criticism. If you want a masked killer with a slow hand, Johnny is your guy. That said, though Johnny’s kills are memorably cruel, In a Violent Nature is not a conveyor belt of bodies either. The relentlessness here is truly about the execution. While the first kill is artfully edited–just an appetizer really–the majority are slow and sustained, going on and on and lending an eerie passivity to events that, with different direction, could just be a simple schlockfest. One of the final kills we see isn’t even particularly gory, but after a fast-paced action sequence, Johnny takes [checks watch] seven meticulous minutes to murder the guy, and making him wait is the point.

There are people who will not enjoy In a Violent Nature, and that is fine. I have never seen, and suspect am unlikely ever to see, a film with so much gore that is absolutely not for gorehounds. And I think that this movie will be unsatisfying if you look at its use of Johnny’s POV as a gimmick, not least because the camera does leave his shoulder at chosen moments, notably the ending, which cuts away from its Final Girl frozen in expectation. With apologies to Bodies Bodies Bodies and the whole X trilogy, there is something about In a Violent Nature’s approach that makes it the most A24 slasher possible*–which is to say provocative, yet still ineffably arty. It’s grad school grindhouse; a rotten severed head squelching around in a nice sustainably-inked canvas NPR tote bag. Provocative, arty, and sustainably-inked myself, In a Violent Nature was very much my thing, and I wouldn’t mind a YouTube playlist of Johnny crunching through the woods to study by either. It does ask something of its audience for sure, but you know, anything worth having is worth waiting for.

~~~

Angela is now patiently waiting for the inevitable announcement of a Johnny Funko.

Categories: Horror