Assembled gentlefolk, respected colleagues, dear friends, lately I have come among you discussing terrible people: Tamiya Iemon from The Ghost Story of Yotsuya, who is the absolute worst, as well as the jerk aliens of Space: 1999. Today I discuss another terrible person of literature, stage and film, Victor Frankenstein. And I come before you to reveal a simple truth. You might have conversed about Frankenstein and referred to the being Victor Frankenstein sewed together and animated only for someone to interrupt and say, believing they are helpful, ”Actually, Frankenstein is not the monster. Frankenstein is the doctor.“ Perhaps a wag adds, ”Well, Frankenstein is the real monster.” And everyone chuckles and raises their glasses of port, Madeira, or sherry.

I will not dispute any truth that drags Victor Frankenstein, one of the worst gentlemen of literature, stage and film. But if we are going by the book that Frankenstein is not the monster, then the truth is that Frankenstein is not the doctor either–at least not unless Victor Frankenstein’s creation gets a medical degree. Getting the degree your deadbeat dad didn’t is the best revenge. Victor dropped out of the University of Ingolstadt. (Go Fightin’ Frankensteins!). Actually, he’s not the doctor. He’s Mr. Frankenstein.

Victor Frankenstein is often presented as a scientist with theories so advanced that contemporary scientists with a backwards understanding of the true nature of the world scoffed and sought to silence him, unable to understand what he showed them. Dr. Frankenstein is a genius with astounding, incandescing equipment that harnesses lightning to bestow life on what once lived. He creates a new being from the once scattered remains of others, his creature, known to some only as Frankenstein’s monster. And known by heretics like me, as Frankenstein, while Victor is “Victor.” But whatever you call Victor and his creation, Victor is a tech bro of the Romantic Era who drops out of school to follow his passion, and creates something intended to save humanity that really did not save humanity.

In Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (New York, Penguin Classics, 2013), Victor left his family, his beloved cousin Elizabeth, and his largely self-led schooling in Geneva to attend the University of Ingolstadt. Shortly thereafter, he dropped out to pursue his own obsessions, ones that stemmed from reading old alchemical texts as a boy–particularly after his father derided the works of Early Modern Hermeticist and Kabbalist Cornelius Agrippa (1486-1535) as “sad trash”(40). It’s hard to imagine choosing a more tech bro university in some ways than the University of Ingolstadt—including maybe even Stanford. The University of Ingolstadt closed in 1800, shortly after Victor likely attended it, and eventually moved to Munich, becoming Ludwig Maximilian University, which you can attend today if you would like and is probably the home of the Center for Undead & Frankenstein Studies.

But in 1790, Victor’s likely time, the University of Ingolstadt was associated not only with prestigious professors and a longstanding history of academic excellence in canon law, but with Adam Weishaupt, philosopher, professor of law, and founder of the Illuminati, a secret society banned in 1784 and popularized ever since in conspiracy theories and art like Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea’s Illuminatus! Trilogy (1975), Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons (2000), the often underappreciated cartoon Gargoyles (1994-7), the Deus Ex video game series (2010-16) and innumerable others—not including breathlessly credulous YouTube videos. Ingolstadt, Weishaupt and the Illuminati had different associations for Shelley in 1818 than they do now. Frankenstein is a novel that privileges education, books* and rationalism and it’s likely that Ingolstadt–Weishaupt and all–is a reflection of that. So I am not saying that Victor was a member of the Illuminati, but reading Frankenstein now, of course Victor would go to a school where the founder of the Illuminati taught. (Until Weishaupt fled Bavaria in 1784, after being accused of treason). If the university still stood in Ingolstadt now, it would be crawling with edgelord tech bros who brag about their association with Weishaupt and the Illuminati. As it is, I would not be surprised to discover there was a matter of an expired Bavarian student visa after Victor stops attending classes.

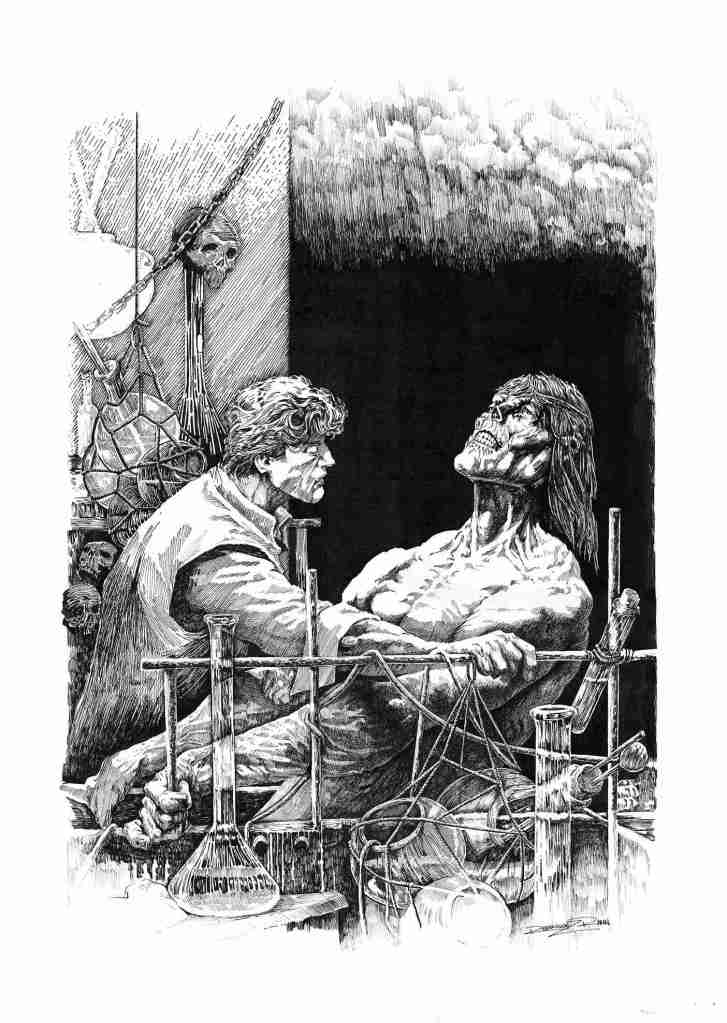

Unlike his tech brethren of the 21st Century, Victor is not obsessed with colonizing Mars to “save humanity,” draining young people of their blood to rejuvenate wealthy aging flesh, re-establishing a feudal order in a post-apocalyptic hellscape, Dark Enlightenment, escaping the computer simulation, or creating conscious AI in order to obtain immortality. Instead, Victor wants to “unveil the face of Nature” and discover the secret of life (41). Like his tech brethren of today, Victor longs to live in a different world–a more exciting and interesting world, one answerable to his will. And like his tech brethren all too often do, he is willing to take the calculated risk of other people’s lives to achieve his vision. In the novel, Victor labors alone for long hours in his student apartment creating a body that he intends to imbue with new life. He made this being without considering the implications of making it, focused only on his impulsive desire. He, too, dismisses law, ethics and the administrative processes of human research as something governing other people. He snatched body parts from graves and the university’s dissection lab and stole skeletal remains from church charnel houses. And once he succeeded, Victor fled the living being–the enormous and enormously powerful child–he created. He took no responsibility for it or the repercussions from abandoning it. In the end, Victor and his obsession cause so much destruction for himself, his creation, their loved ones, and the world around them from Ingolstadt to Geneva to the arctic sea.

As a youth, Victor fell down his own rabbit hole, not of chemtrails, ancient astronauts, lizard people, secret bases on Mars, Satanic pizzerias or even the Illuminati, but alchemical texts from authors like Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus (1493-1541) and Albertus Magnus (1200-1280) offering him the means to obtain the Elixir of Life, the Philosopher’s Stone, and the raising of spirits and demons (42). What attracted him were the promises to achieve something beyond the boring, finite, circumscribed limits of the natural world.

I had a contempt for the uses of modern natural philosophy. It was very different when the masters of the science sought immortality and power; such views, although futile, were grand; but now the scene was changed. The ambition of the inquirer seemed to limit itself to the annihilation of those visions on which my interest in science was chiefly founded. I was required to exchange chimeras of boundless grandeur for realities of little worth. (48)

Victor liked the idea of being involved in a titanic cosmic and universal process, of harnessing the very powers of life itself. Natural science just didn’t have the same appeal and flair for him. And at the University of Ingolstadt (Go, Ill-Tempered Illuminati!), the mild-mannered chemistry teacher Professor Waldman accidentally triggers Victor’s old desire to raise demons and summon spirits, but in a new way.

“The ancient teachers of this science,” said [Waldman], “promised impossibilities and performed nothing. The modern masters promise very little; they know that metals cannot be transmuted and that the elixir of life is a chimera but these philosophers, whose hands seem only made to dabble in dirt, and their eyes to pore over the microscope or crucible, have indeed performed miracles….They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers[.]”

Such were the professor’s words—rather let me say such the words of the fate—enounced to destroy me. As he went on I felt as if my soul were grappling with a palpable enemy; one by one the various keys were touched which formed the mechanism of my being; chord after chord was sounded, and soon my mind was filled with one thought, one conception, one purpose. So much has been done, exclaimed the soul of Frankenstein—more, far more, will I achieve; treading in the steps already marked, I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation.” (49)

Victor does not crack open Cornelius Agrippa once more. Instead, Victor begins his project of making Frankenstein. He researches anatomy. He spends two years stealing body parts and creating a new life from the remains of the dead. Victor decides to make his creature beautiful. Victor fantasizes about how he will be received as the being’s creator and what his accomplishment will mean for humanity. He expected to receive love, admiration and gratitude from his creation and from others astonished by his revealing the secret of life itself. But when he succeeds, Victor is shocked and disgusted by what he has wrought.

The different accidents of life are not so changeable as the feelings of human nature. I had worked hard for nearly two years, for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health. I had desired it with an ardour that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. (58)

Victor flees his apartment, falls into a nervous collapse, recovers, and spends months trying to not think about the creature. Until Frankenstein finally comes to find his creator.

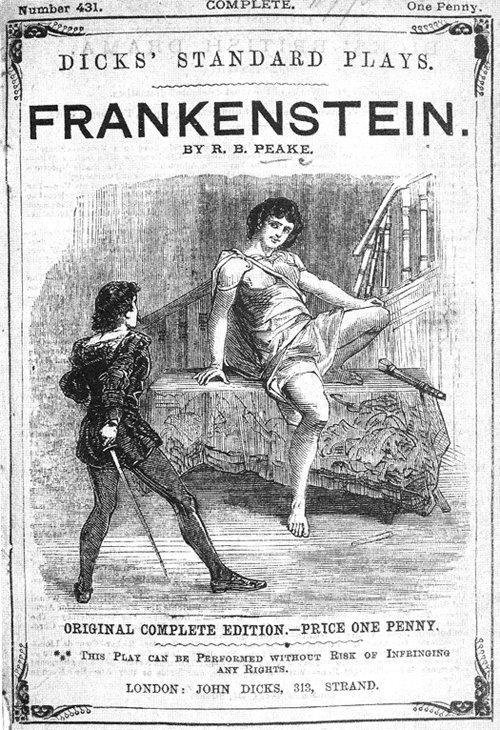

And so Victor never finishes his degree program at the University of Ingolstadt (Go, Fightin’ Wieshaupts!). Victor Frankenstein became a doctor in the same way that Victor Frankenstein’s “vile insect,” “abhorred monster,” “wretched devil” (102), and “filthy mass that moved and talked” (149) became “Frankenstein”—outside Mary Shelley’s novel. It’s an honorary doctorate awarded in popular culture as people adapted and re-adapted Shelley’s story to their needs. Over time, Victor Frankenstein went from a student doing creepy experiments in his apartment to a doctor with a castle—and even a baron with generational wealth perhaps from a South African mine in the Hammer Studios film adaptations and implicitly a baron when Baron Wolf von Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone) appears as his other son who inherits his predilections and his wealth in Son Of Frankenstein (1939).

I do think Frankenstein has a greater claim to his name than Victor does to his subsequent doctorate and baronhood. After all, Frankenstein’s “monster” is a person. And if you encountered any other child whose father refused to name them, well, you would not decide they could never be named to honor the pain of abandonment they felt. On occasion, in series like Dark Shadows or Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Frankenstein is called, “Adam,” after Frankenstein’s own appeal to Victor as a negligent creator of life in the novel. I respect that.

I entreat you to hear me, before you give vent to your hatred on my devoted head….I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king, if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other, and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature: I ought to be thy Adam; but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous. (102-3)

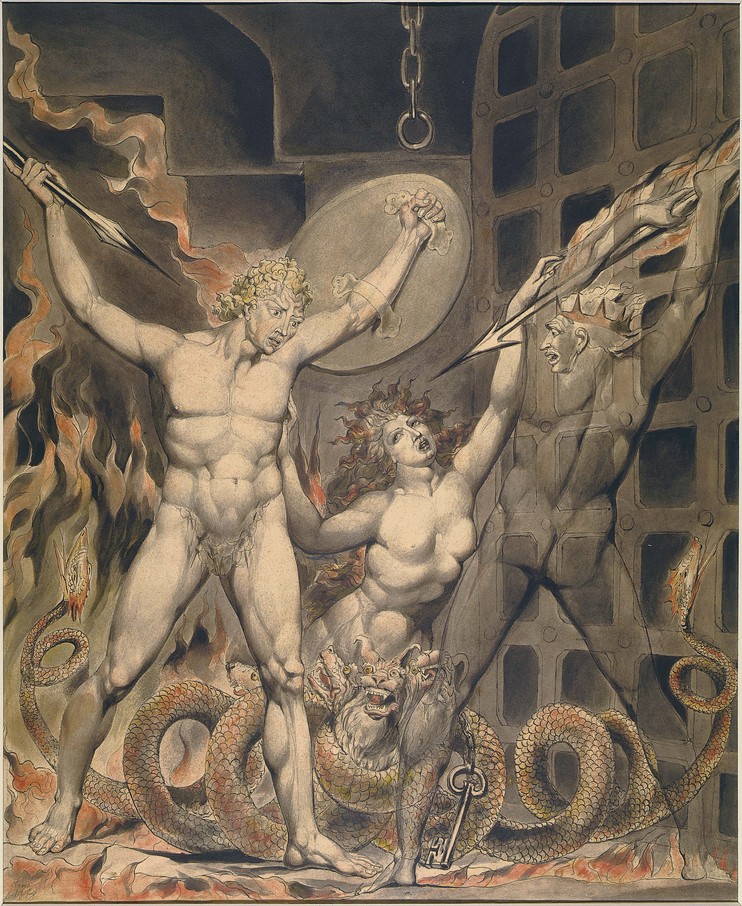

It’s probably for the best that Victor did not name his bespoke son. It’s hard to see Frankenstein wanting to be called “Adam Frankenstein” even during this conversation. Yes, he should have been Victor’s Adam, but he wasn’t, which is the point of his complaint. Calling him “Adam” to make up for Victor’s awful parenting might feel more like mockery to him. Frankenstein already identifies more with the fallen angel Lucifer in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), and is far more likely to choose “Lucifer” or “Satan” for his name. And not many people are going to call him that. Honestly, I think Frankenstein dodged a bullet. He could have been named something like Opus Victorī, Tria Prima or Techno Mechanicus. Or maybe the Work-Product of Frankenstein when the University of Ingolstadt sued for the sole possession of the IP of Frankenstein.

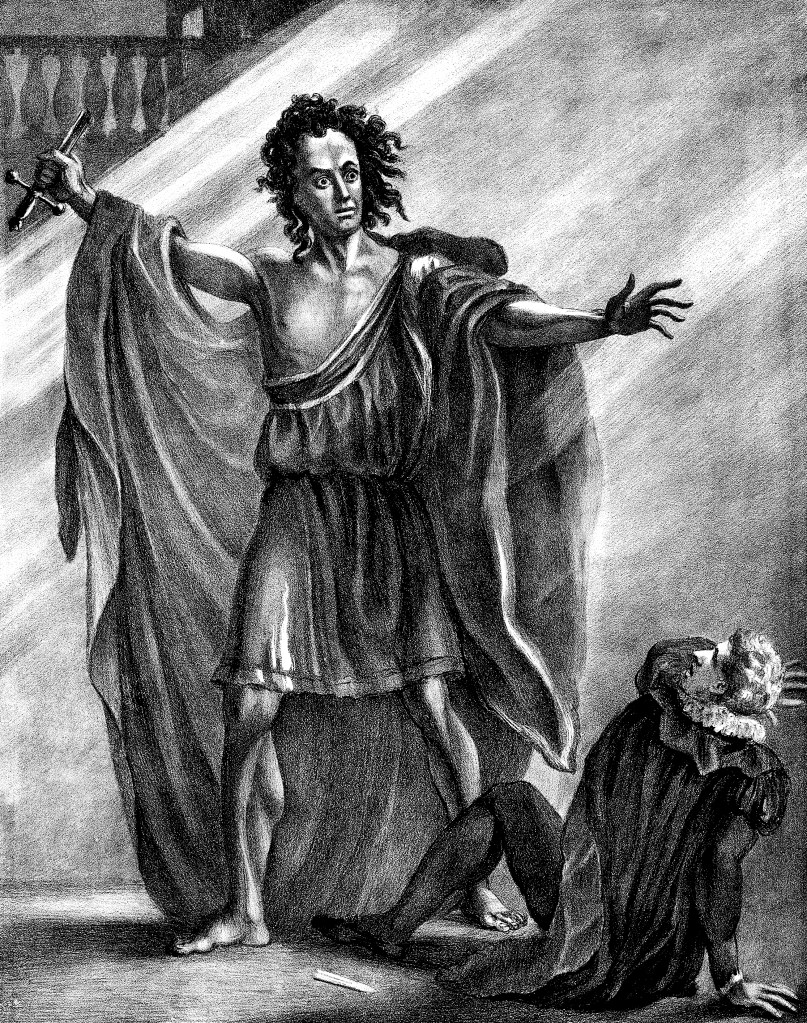

One of William Blake’s 1808 illustrations for Paradise Lost.

For me, Victor’s doings are not so much an affront or a rebellion against God or the natural order, but an affront to his creation—his child—and to other people. Victor Frankenstein is a terrible father as well as a tech bro, an all-too-common combination. Victor created a life and took no responsibility for it. He refuses Frankenstein both affection and the mate Frankenstein demands. Though I do think that refusing to make another person expressly as a bride for Frankenstein was a rare right call on Victor’s part. Instead of creating someone only to abandon them, Victor could have married and had children with his beloved cousin Elizabeth, which I have to say is a little uncomfortable for me, but it’s better than what he does otherwise. Victor could even have a passel of children, like a tech bro who loathes the weakness of his sexual urges and uses in vitro fertilization to create more male children to reflect his own glory and to try to overcome his fear of death and personal extinction genetically. But to get back to Frankenstein, Victor could have graduated and actually become Dr. Frankenstein. He could have become a professor and continued creating chemistry instruments, as he had as a student (52). This would have truly benefited humanity, something tech bros often claim they want to do as they damage and ruin the lives of individual humans. Victor could have his own version of immortality with something like the Frankenstein Pipette, the Incandescing Frankenscope or the Illuminative FrankenCoil, beating out Tesla by 100 years! His inventions could take their place beside the Ehrlenmeyer flask and Bunsen burner. Victor could have had a life that would have a much better outcome for himself, Elizabeth, and the people around them.

In fairness, I will acknowledge that Victor’s weird discoveries are his own. He did not buy anyone else’s work and erase them, as some tech bros do. And to his credit, Victor realizes his folly and mistakes. He’s still a terrible person and a worse father, but his self-awareness is more than I expect from any of his current brethren trying to impose their will and foolish vision on the world to all our detriment. Unfortunately, Victor’s self-awareness does not stop father and son from visiting their wrath on each other until both are dead on the Arctic ice.

*The Lilly Library in Bloomington, Indiana had a fantastic exhibit dedicated to the 2ooth anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. One of my favorite parts of the exhibit were a pair of cases dedicated to the books that Victor and Frankenstein read throughout Shelley’s novel. If you missed the exhibit, the program is available online and well worth your time. Find it here.

Hey, it’s a couple of other things I’ve written about Frankenstein:

“The Specter of Frankenstein.”

“The Shrieking Horror of Castle Lemongrab.”

~~~

Carol Borden’s mother was the lightning.

Categories: Horror, Science-Fiction

8 replies »