Spoilers for all Dragon Age, y’all.

I have always believed the world would be a kinder place if more people played Dragon Age games. It’s true that BioWare’s high fantasy series hews to a formula common to all their RPGs—thoughtful writing, beautifully-acted companions representing competing ideologies, and above all, player choice and consequence—but for me, Dragon Age is the developer’s deepest well. Much of this rests on a Goldilocks level of worldbuilding: distinct enough from other fantasy worlds to take seriously on its own terms, but near enough to human history to fully take to heart. You know, don’t you, when dealing with enslaved elves and traumatized templars and mages who must submit to imprisonment or else be lobotomized, these stories are no fantasies. Of course, Dragon Age is full of fighting and magic and romance, but the real draw, at least for me, is the test that the games put to the player, a test with no easy questions and no right answers. And the brilliance of Dragon Age’s verisimilitude is that the questions themselves may be wrong, based on rewritten histories, unreliable narrators, cultural misunderstandings, and political lies. Just like in real life.

Beginning with 2009’s Dragon Age: Origins and culminating with 2024’s Dragon Age: The Veilguard, the Dragon Age developers have unwound a masterpiece on the scale of a grand novel series. (There is, of course, also a novel series. And comics, short stories, a fiction podcast, an animated series…) What began as a blood-spattered tale of last chances, regicide, and plague in the southern kingdom of Ferelden ended in the slave-holding northern empire of Tevinter with a multinational campaign against self-appointed “gods” who, for the sake of power, unleashed blights like that which consumed the first game, authoring ages of untold suffering and sorrow. With a far-reaching 100-hour campaign, Veilguard is the natural escalation and fulfillment of the previous three games, with the gods’ crusade paying off revelations a long time coming. And the reality the fourth game reflects is ever less distant, as the gods enlist the support of corrupt governments, a zealot cult, and an extremist militia, all of these devoted to the idea of returning their people, whoever their people might be, to rightful, racialized dominance. And again, these stories are no fantasies and there are still no easy questions, no right answers. Except fighting the fascists. This game kills fascists. That one is a gimme.

Fascists don’t like Veilguard much either, as far as that goes, and this is part of why it has become a flashpoint for Internet Discourse since its release. Every Dragon Age tends to rile them up a bit, but Veilguard really pissed them off. I do say part, because I would not dismiss out of hand legitimate criticisms around the changes in gameplay and art style or about the story itself. Tastes differ, mileage varies. What’s more, Veilguard plays out in a different part of the world, meaning that scores of agonizing player choices from the previous games are just…not germane.* That’s a bitter pill to a fan who, up to this point, felt like a coauthor. And that’s before we even approach how publisher EA’s corporate mismanagement kept the game in development hell for a decade. The unfortunate truth is that the story of Veilguard’s making is at its heart also a story of its unmaking in the public eye, and while that isn’t unimportant, it is a different essay. I would rather talk about why Veilguard serves as such a powerful culmination of the series to this point, and what is so effective and valuable about the way it finishes the story. Unfortunately, I think that includes the editorial choices that meant perhaps we didn’t get to go to Skyhold or see Acting Viscount Aveline and it doesn’t really mention who is ruling Ferelden. But I do want to call out the choo-choo hate train triggered by Veilguard’s [weary sigh] “wokeness,” because, of course, the wokeness is the point of Dragon Age. It always has been. All those false histories among the elves and the qunari, the religious extremists you confront in every culture, the oppression of mages in the south versus the oppression by mages in the north, the civil wars fought for lies and mistakes—how do people miss this? And yes, Veilguard is the wokest, queerest Dragon Age yet. More please. The popular sentiment among fans of the game is to say Veilguard didn’t deserve the hate, but in a sense it did, it richly earned that particular hate, because hate like that is a medal awarded by the worst people for the worst reasons.

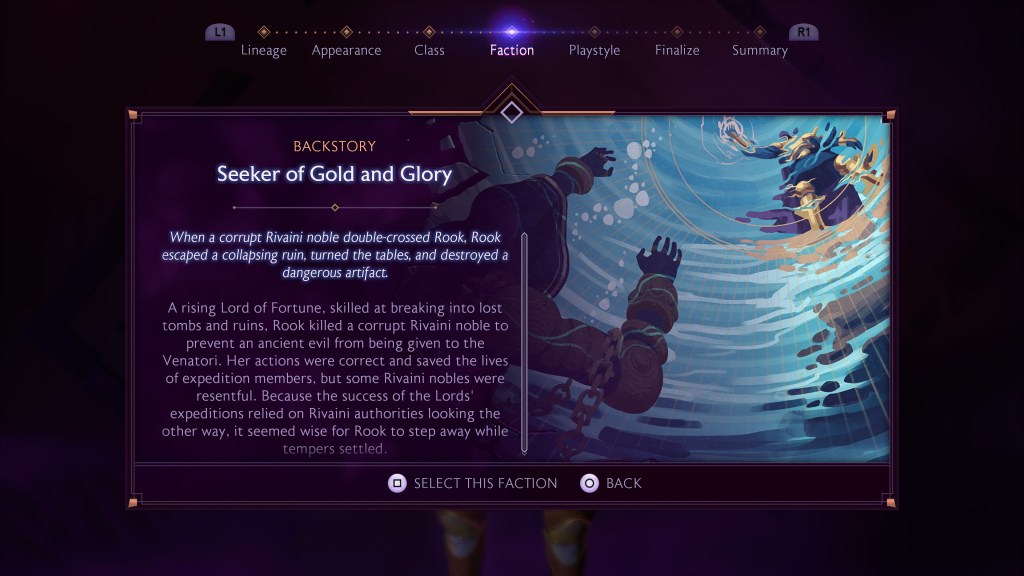

So, that bit of housekeeping done, why is bright, beautiful, hopeful Veilguard a perfect end to a story that begins eye to eye with desperation and helplessness? Let’s start with you. Every Dragon Age game has its own player character, and you have a certain amount of latitude in deciding who that character is before you ever start choosing your own adventure. (Dragon Age 2 is the notable exception, in which you must play a human of the lesser nobility on the run, but for what it’s worth, DA2’s Hawke’s background is layered with plenty of stakes for whatever route the player chooses.) In Veilguard, that character goes by “Rook,” though their real name is up to you. Also up to you: your look, your background, your race, your sex, your gender identity, your pronouns.** You choose whether you shoot or stab or zap. And once your character is out in the world, there are additional roleplay options that come up through dialogue in the game—not gameplay choices, but dialogue about your background, attitudes, and beliefs—and I really liked these “yes, and” improv opportunities to give my Rooks more texture and independent character. I’ve played three elven ladies so far, pretty homogenous choices given the breadth available to me, but each still has a profoundly different relationship to her cultural heritage and experience of racial prejudice.

What you don’t choose is whether you are a hero. In past games, the player’s goodness was measured by the player’s choices, not their adversaries’. Which is to say you aren’t good just because you’re fighting bad things. Practically speaking, you might not be able to fully turn villain, but you could certainly be a dick. And the player’s relationship with their companion characters might bloom or sour depending on how much the companions, who come with their own biases, approved of the player’s choices. They could fall in love with you. They could betray you. They could leave. Or you might could change their minds about the world.

But Rook, whoever they are and wherever they come from, is a hero. Not a reluctant hero, not an asshole who does heroic stuff for petty pragmatism, not a person with heroism thrust upon them. At the game’s start, Rook has already earned their place in the big events following the climax of Dragon Age: Inquisition. It is no accident that, much as you had to be a human noble destined to choose sides in a civil war in DA2, each of the six origins stories for Rook in Veilguard involve Rook doing something unabashedly heroic that angers the nobility and/or Rook’s faction leaders, putting them on the path to become second-in-command to series mainstay Varric Tethras in the game’s opening. You retain all the freedom with how your Rook will respond, or not, to events in the game, using the same dialogue wheel the series has employed since DA2. But the differences in Rook’s responses in Veilguard are more about context than virtue. You’re not perfect, you may be terse or grumpy, you might like to smooth talk or punch first, but you do good things for the right reasons. And contrasting with previous games, some can find Rook’s hardcoded virtue a constraint or even an unacceptable loss, particularly when so much of the previous games was painted in blood and moral gray. The shine of Rook’s halo might well make you squint if you’re so devoted to the gloom. But the movement away from that tenor of character has also been a steady ascent through the series, from the Hero of Ferelden, who is more or less pressed into the service of the Wardens, to Hawke, caught up in events as a refugee, to the Inquisitor, whose all-but-accidental actions make them a folk hero in the wake of DA2’s climax. And honestly, through three playthroughs (so far), I felt the depth of characterization afforded me in varieties of goodness exceeded the thinner options at greater extremes of morality.

Although I confess that I have never enjoyed exploring dickishness. That is my bias.

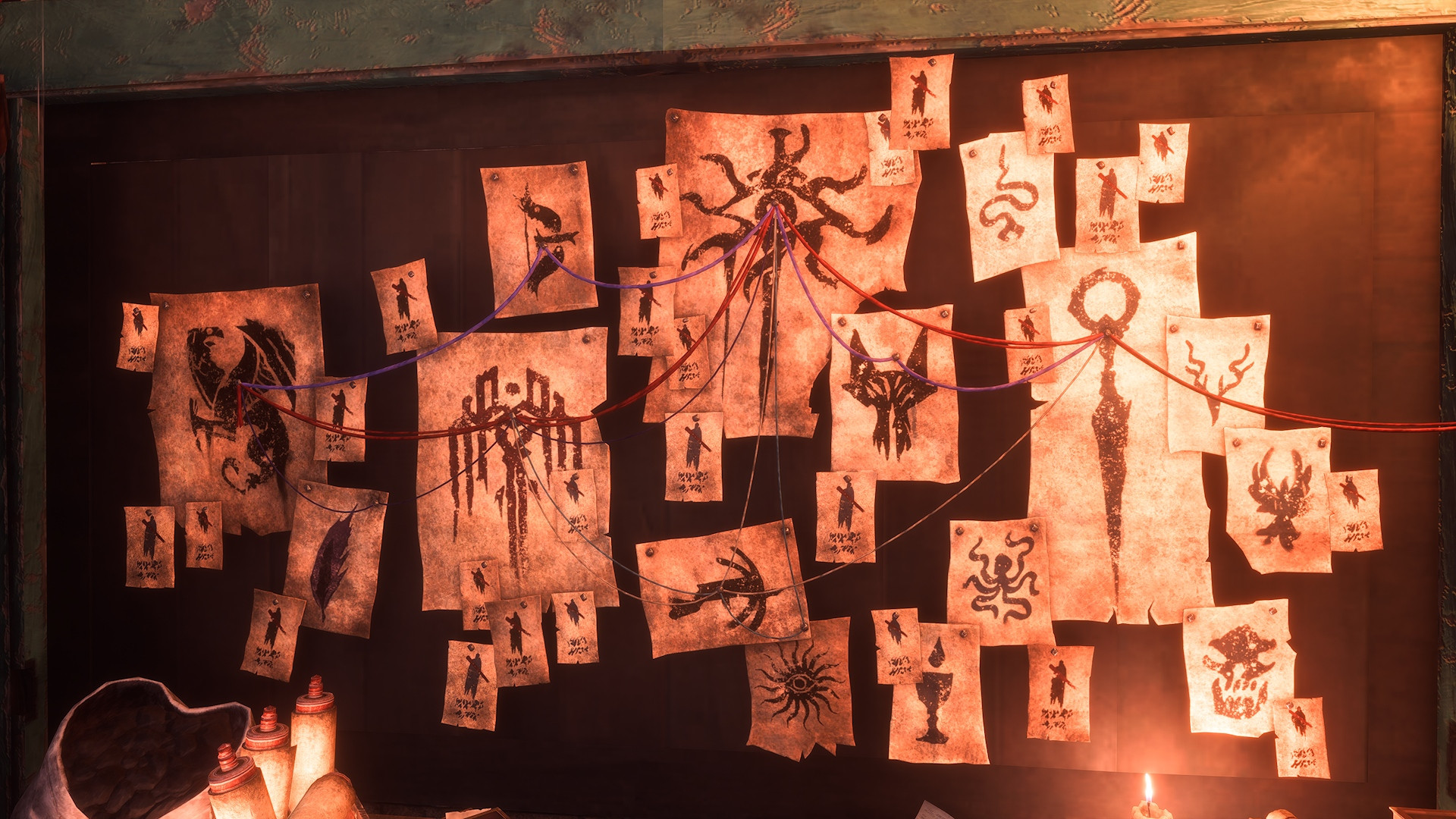

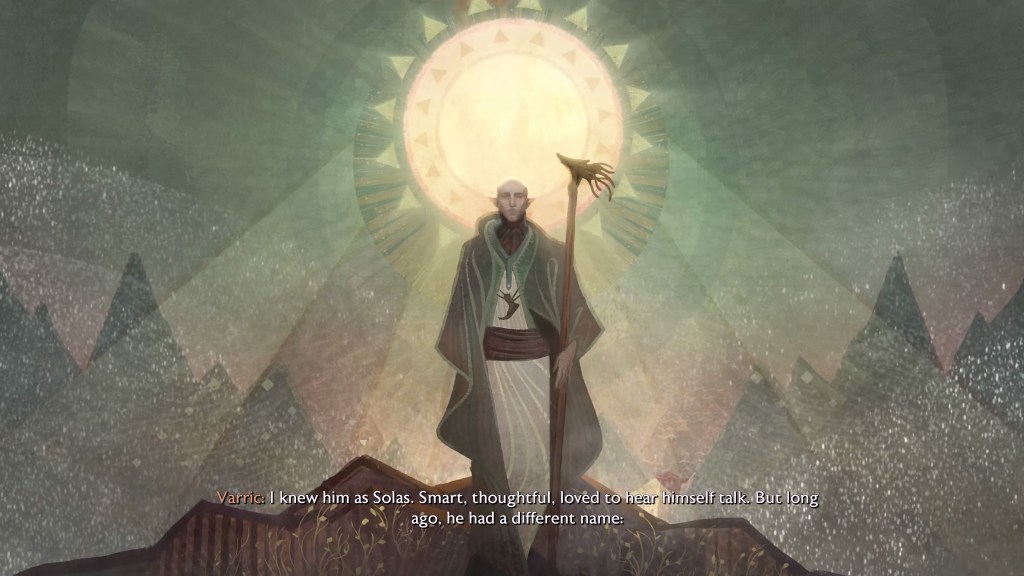

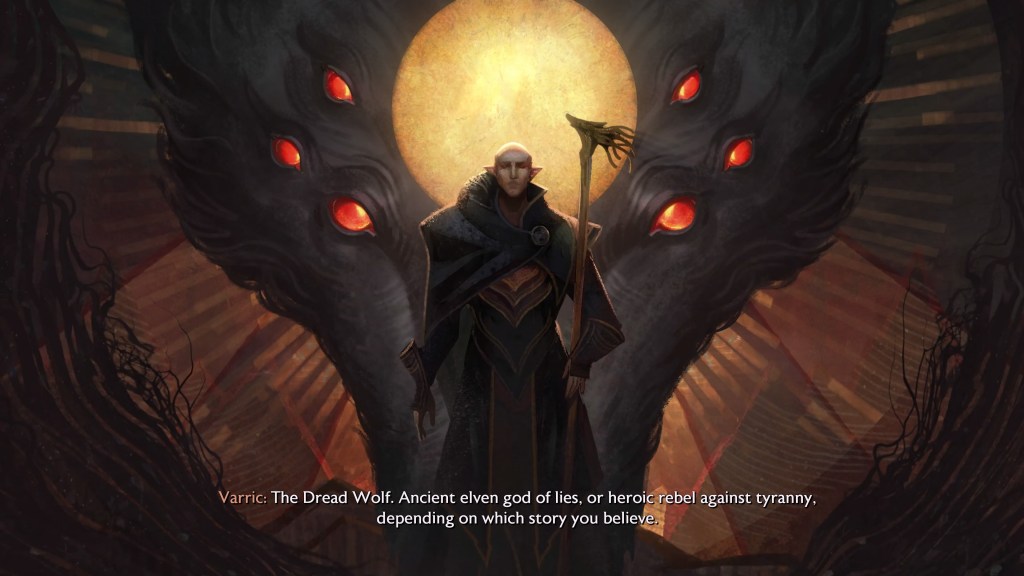

It’s not just that you need a hero experienced with disrupting Authority at the helm of this thing. There is a buffet of moral gray being served with seconds in Veilguard, primarily by the character everyone expected to be its Big Bad Wolf. Inquisition ends with the revelation*** that thoughtful elven mage Solas was secretly the trickster elven god Fen’Harel, aka the Dread Wolf, and he was manipulating the Inquisition in a much grander scheme to unmake reality as we know it. He intends to do this by tearing down the Veil that separates the physical world from the more metaphysical magical realm of the Fade, thereby restoring the world to a previous golden age at the low, low price of pretty much everyone currently living. He has very sorrowful reasons for this, self-sacrificing and noble reasons he believes, and depending on your choices in Inquisition, he may be a trusted friend or even the Inquisitor’s lover. Whether you personally believe Solas is right actually, can change course, or must be put down like a dog is up to you. Rook cannot entertain the first idea, much as the Inquisitor couldn’t, because the cost in lives will be unimaginable. Yet the game will insist that you grapple with the destructive price of Solas’s pure motives all the way to the end. And to do that conflict real justice, Solas needs a hero as strong-willed and as sure as he is to be his adversary.

It will not be a simple battle between Rook and Solas though. Any tidy resolution to Inquisition is quickly forfeit as Rook interrupts Solas’s apocalypse in the very first mission of Veilguard, accidentally releasing the two other remaining elven gods onto the world. Unlike Solas, who rationalizes a greater good, these gods are purely malevolent enslavers. They, too, want to turn the clock back, but to the days of their unlimited rule before Solas overthrew them. Not much ambiguity there, but good contrast. Solas is sidelined by events, relegated to advising Rook as they seek to defeat two sadistic gods and their Super PAC of bad guys rising across the nations of northern Thedas. But you’re not only fighting the gods and their allies, all of whom are explicitly fascist. You’re contending with the example of the Dread Wolf, the only one who has ever prevailed against these ruthless creatures, albeit only with the great and principled sacrifice of other people. Rook’s background as a rebel with a cause is key to that framing, and so too their natural heroism and their bond with their companions. Solas will highlight this difference as he counsels Rook, encouraging them to be clear-eyed about the necessities of war, i.e. you gonna have to sacrifice somebody sometime. Solas clearly regrets his own sacrifices, but he does not seem to consider companions and allies could ever offer an alternative to an end rather than a means to one.

And that brings us to the companions: who you’re fighting alongside and who you’re fighting for. Friendship is magic in Veilguard, and literally the only way to improve companion skills, but you’re gonna have to work for it. The game begins with Varric and Inquisition fan favorite Scout Harding, but Rook will acquire six more allies, all essentially virtuous, but by no means easy company. They will squabble. They will fight. Sometimes they will trauma bond. And as the saying goes, everyone is fighting their own hard battle. For example: assassin Lucanis is looked down upon by some on the team as a blade for hire, and after torture in captivity leaves him host to a demon, there are even more reasons to doubt his help. Meanwhile Lucanis’s biggest doubter, Davrin the Grey Warden, pledged to self-sacrifice and prone to self-righteousness, will have to confront some unsavory truths about his own chosen order and what price they once paid for victory. Dragonslayer Taash, who privately wrestles with an ascetic qunari heritage as well as fitting in as a woman, low-key bullies necromancer Emmrich, the gentlest and most compassionate of souls, but still creepy to Taash, and most of the team, because death. But where your companions will bicker and distrust, you can help them overcome their differences, and their relationships will also independently evolve as you fight together. This is important because the problems your companions bring with them will branch and trace back to the gods’ pernicious influence, often in unexpected places. Your enemies are working together, too, so Taash’s fight against the Antaam in Rivain is not at all at cross purposes with Neve’s fight against the Venatori in Dock Town. The personal is political and that’s a major part of Veilguard’s message, as your companions’ and their factions’ strength is tied to how you meet their homegrown challenges. You cannot sacrifice someone else without suffering a penalty to your own strength. No one is free until everyone is free. Trust, there are many possible endings to Veilguard, but the only hope to save everyone is…to save everyone.

I appreciate, too, that Veilguard features several moments where you can reflect on loss throughout the game. This is not a story where you simply vault from one boss fight to the next, uncaring of who falls or what it costs. The fallout of your decisions is ever present, whether it means watching homeless dying on the streets or witnessing the gory remnants of public executions. In Dragon Age: Origins, you frequently entered cutscenes covered in blood spatter, but that is no more mature or realistic than Rook entering a room filled with the fallen on the final approach to the gods’ redoubt and quietly paying their respects.

So we’re back to the wokeness. I told you it was the point. Empathy and community building, kids. It’s not only the point of Veilguard, but the prevailing lesson of the Dragon Age series, where, again, stunning, ideologically-driven betrayals drive each narrative and make the unintended and the least of us suffer, only for a hero to pick themselves up and start figuring out how to go on and who can help. You can also see how those thorny Dragon Age companion relationships are the They Live glasses all of us need at one time or another, teaching us how to empathize with someone you never even wanted to know, or maybe to forgive someone you thought beyond redemption. Or how beliefs are often flawed, but no one’s rights are negotiable. Or how no one is free until everyone is free. This game kills fascists. Literally, in the course of the game, yes–I will leave it up to you and your ending what that means for Solas****–but more importantly, its soul is pure fascist bane, centering empathy, intimacy, heroism, community. Multiple overarching storylines intersect to highlight the ways history and faith can be twisted to alienate and control people, as well as how the best way to fight fascism is always with each other. I hope that this isn’t the last Dragon Age game, but this is absolutely the world the Warden and Hawke and the Inquisitor fought for. And corny as it may seem, knowing that this story is out there right now gives me hope for our world, too.

*Yes, it would have been great if we could have gone to the southern front. Yes, I feel like we should have a clear indication of who the Divine is. Yes, I am totally in favor of more of this game. I wish it were so.

**Carol pointed out that your pronoun choices are not fully customizable if you preferred something like she/they.

***I am counting Trespasser as the end of Inquisition.

****I know I’m being harsh, but Solas is my canon DA:I LI. He can take it.

~~~

Angela thinks that the fact that critics blast Taash’s story, which encompasses their fractious relationship with a distant mom, their feeling of dislocation being raised as a qunari in Rivain, the secrecy about their ability as a fire-breather, falling in love, as well as their unhappiness with being identified as a woman, as being “only about gender” shows how we need many, many more stories like Taash’s.

Categories: Videogames

2 replies »