In 2020, after decades–literal decades–of Final Fantasy VII side stories, prequels, sequels, spinoffs, and cameo fan service, Square Enix rolled out Final Fantasy VII: Remake, the first part of a planned trilogy which would see the beloved 1997 Japanese role-playing game reborn into the modern gaming era. It is hard to overstate how important the original game was, not just for fans of the series, but for the very first Sony PlayStation, for role-playing games, for mainstream video games, for anime fans, particularly in the west, and for, well, modern video gaming as we know it. FF7 appeared at a watershed moment in video gaming, as its penetration into consumer culture was becoming desirable, affordable, and cool again, and while FF7’s legacy and critical importance have never really been out of the spotlight over the last twenty-six years, it’s still a game that its contemporary audience can’t really be objective about.

As briefly as my fanlady brain can manage, the outline of FF7 is this: Our main character, spiky-haired, massive buster sword-wielding Cloud Strife,* is a mercenary hired by the AVALANCHE eco-terrorist group to destroy a mako reactor, the sole energy source for the cities of Cloud’s world, siphoned straight from the planet’s literal blue-glowing lifestream. (Nuclear energy cautionary tale in a Japanese sci-fi/fantasy story! You don’t say!) While Cloud initially is a passionless hired sword, as he faces danger with the AVALANCHE team, including leader and Mr. T analogue Barrett and Cloud’s childhood friend Tifa, he begins breaking out in signs of heroism. Eventually they end up protecting cheerful flower girl Aerith, who has a special connection to the dying planet that the Shinra Electric Company would love to exploit. As the group crosses the legendary SOLDIER Sephiroth, Cloud’s commander/mentor who has long been thought dead, Cloud slowly realizes he might not be the ex-SOLDIER he thought he was. Several others join the party over the course of the game–a wolf cat guy, a ninja girl, a cat puppet, a vampire guy, a smoking pilot–all with their own compelling reasons to fight Shinra, and like every Final Fantasy, eventually everything is about the end of the world.

It’s a classic, but convoluted story, especially once Cloud starts getting all fugue state in the back half of the game, and part of how it succeeds draws from the repetition of Final Fantasy’s favorite themes–the planet incarnate, humans exploiting nature, unreliable memories, a cataclysm from the sky–but unquestionably, it also wins on vibes and looks. We can debate Sephiroth’s motivations, but part of why he is an all-time perfect villain is a) we know just enough to sympathize with him AND NO MORE and b) he looks amazing. While the game was a 3-disc (!!) monster back in the day, much more is felt and implied than outright explained or seen. Much of this reflected limitations of technology, not appetite. Though the game’s graphics were jaw-dropping in 1997, watching the FMV sequences where Cloud, Aerith, and Tifa negotiate reality and memory in dream-like circumstances, one can appreciate that the player’s imagination is doing as much heavy lifting as the PS1’s processors.

And so in the PS5 era, as the saying goes, we have the technology to be more thorough and literal in recomposing everything we saw, and everything we thought we saw, in FF7 way back when. It is the unfortunate truth that video games as an art form depend on their delivery system in a way that makes them uniquely vulnerable to obsolescence. Still again, while translations of beloved classic games from the late 90s are becoming more and more common, it is less true for RPGs than action-focused titles. If the Remake project weren’t already going to be a huge deal because its source material was a huge deal, Square Enix’s approach to its technical and storytelling challenges posed thorny philosophical questions that also chummed the waters with lots of clickbait.

That approach would not be obvious until well into Remake’s story, which purposed to cover the Midgar section of the original game. For context, Midgar represented an early, fairly linear section of the game and only featured the small core group of the game’s playable characters. It is roughly like redoing Star Wars and making the first movie about Luke’s life on Tattooine, ending with him leaving with Obi-Wan, Han Solo, and droid Ernie and Bert. When I started playing Remake myself, I hated it almost instantly. Sure, it was beautiful, but how claustrophobic! They had turned one of my favorite RPGs into just another action adventure, more about timed button-presses than depth or experimentation. And worse, to justify having a full game devoted to it, every minor character became a major character, every brief encounter was a new full dungeon sequence, and in order to shoehorn in glimpses of super bishonen villain ne plus ultra Sephiroth, the story now featured Cloud having strange visions of his ultimate nemesis way before his…shall we say reliability as a narrator becomes questionable. Which could charitably be seen as foreshadowing, but it also felt tacked on, because if you played the game back then you knew Sephiroth didn’t belong in this part. And you also knew when other things didn’t belong. The shadows that follow the game’s cheery magical girl Aerith. The romantic tension between Cloud and a character who, tragic exit aside, barely registered in the scope of the original. These elements were out of true, jarring. Unnecessary.

Or that was how I felt at the time. I don’t believe in spoilers, but I do think it is important not to confuse what you expected, or maybe what you hoped for, with what you are reading or watching or playing. It is like substituting an ingredient in a recipe and then blaming the recipe. This is the curse of marketing that follows M. Night Shyamalan’s every film with the specter of expectation of a twist whether or not the story has one or needs one, and it is the fiend of fan entitlement that leads to review bombs a new show before it’s past the first episode. And FF7 was always going to attract a certain possessive scrutiny from fans, fans who are apprehensive to lose what they loved. Square Enix had an opportunity to simply do a faithful upscaling of the game–add the quality of life improvements modern gamers expect, expand a few a sections, add another bonus Weapon boss maybe?–but that was not the answer they offered fans. Spoilers, ha, but at the end of Remake, the party ends up literally fighting fate, and the idea of the whole three-game project becomes at once clear and provocative. We just can’t tell you the same story you already know, not least because the original story pivots on one of the greatest gut-punch twists in gaming history.** Not least because you cannot be the person you were when you first heard this story because this story changed you as much as it changed gaming. The good news is that FF7 tells a story strong enough to withstand reinterpretation.

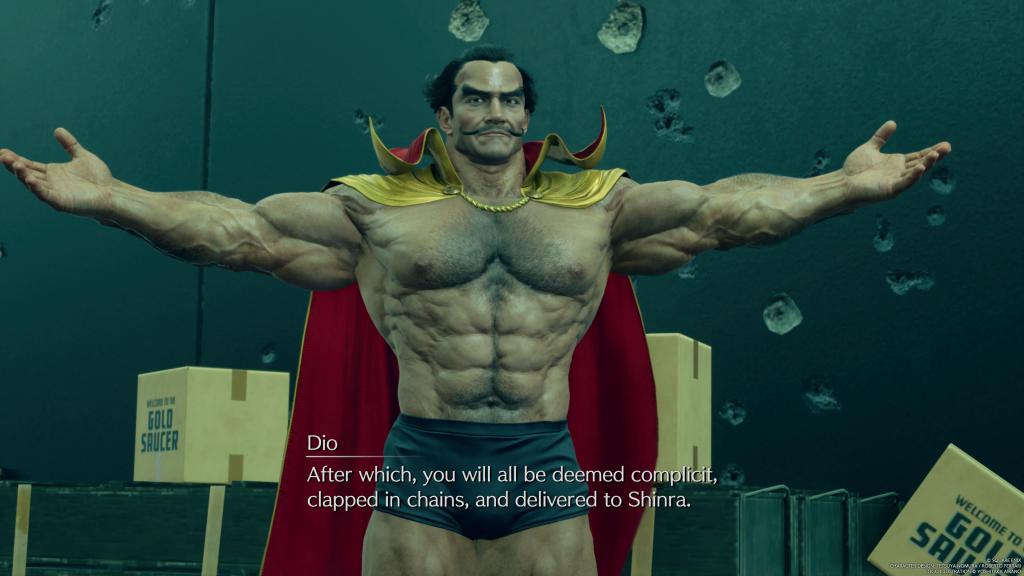

It’s easier to acknowledge the philosophical merits of the FF7 remakes from the vantage point I now enjoy, which is post-FF7 Rebirth. As the second part in the series, Rebirth holds true to the Freytag’s model principle that the middle bit is where things get good. Most of the things I remembered from the experience of the original that I treasured live in that middle bit on FF7’s disc 2, exploring the world with my full party, breeding chocobos to race and hunting materia, and while not all of this is included in Rebirth, particularly the full party,*** the sense of exploration, the joy of discovery, the confidence in my own freedom of choice are all well represented. As a strict comparison with the source material, Rebirth is still padded as hell, but given that the world is so open now, the padding is less noticeable and, to return to my previous point, the padding might not be padding so much as a different emphasis in the story than I was expecting.

Speaking of emphasis, there are so many consequences to the basic FF7 story in the remakes, even outside the sense that the story is not a fixed retelling. I see this in character relationships first and foremost. I alluded to Jessie, a minor character in the original game. Much like everyone, she has a bigger role in Remake, particularly full of romantic aspirations toward Cloud. Spoilers, but she is not appearing in Rebirth. And that is how the original story goes, too. And you could argue that barely knowing Jessie before bad things happen makes the abruptness and capriciousness of loss the more jarring, as well as isolating Cloud from the other members of AVALANCHE, most significantly Tifa. And that is thematically powerful. But it is also a valid choice to see Cloud as more of a team member with this girl with a crush, and also to have her crush contrasted with the more complicated feelings Cloud has for Tifa and Aerith. Or more superficially, just the difference of having Aerith fully voiced–as she was not in 1997–means so much more of her sass comes through. Saintly, pretty, upbeat, fun–all big time Japanese anime heroine characteristics, all extremely clear in Aerith’s characterization. But the rapier wit and boldness? It may have always been there, but it hits differently and even gives Aerith more of a sense of agency when it is actually performed.

Another thing the remakes do exceptionally well is leverage the photorealistic environments of an otherwise anime-stylized world to underscore the crisis afflicting the planet. It really works best when no one even mentions it, and this is especially apparent in Rebirth, where you are largely free to explore and see stunning lagoons and mountain ranges and forests and also to see the ubiquitous encroachment of ick. I haven’t really noticed anyone comment on this, and maybe it’s because post-industrial waste is a pretty common landscape in video games anyway, but that juxtaposition is constantly, wordlessly reinforcing why this story got started in the first place. As I said, every Final Fantasy game, sooner or later, is about the end of the world, and the threat hanging over a large portion of FF7 was a giant meteor Sephiroth was going to drop on the planet, but this is precipitated by the dire abuses of the planet by humans, including the series of experiments that created Sephiroth. It was possible to play the original game and be impressed by Barrett’s passion to save the world from Shinra, but witnessing the ruin of the world spreading without particular commentary or curation from within the game is even more powerful.

So I think what I want to say is whatever the final version of this version of FF7 ends up being–and I have my theories–the pleasure ultimately is in the telling, and there are advantages to this presentation that could not have been imagined in 1997. In contrast, many if not most of the aspects that detract from this version, specifically the sense of wrongness that comes with simple divergence from the original, only exist in conversation with the first game. I am really not sure the padding in either Remake or Rebirth reads as padding to someone who has only ever played these games. Likewise the sense of lost or compromised atmosphere. Objectively, it is hard to argue that a sense of narrative urgency isn’t imperiled by long diversions into an amusement park, but…I love the amusement park, shut up. And there are other choices that I subjectively don’t like, I suppose. (The whole Zack thing. Uh, I don’t know, guys.) But this version of the story isn’t over yet, and I am not going to let my hopes for it be spoilers again.

*Back in the day, [waves cane] we could still rename the characters anything we wanted, and so my Cloud was actually Clive.

**I’m looking with interest at how the Silent Hill 2 film adaptation and remake this year are going to handle the second biggest one I can think of.

*** VINCENT HONEY HOW LONG BEFORE THE STAN SLAM

~~~

Just as in 1997, Angela wants to live in the Ghost Hotel.

Categories: Uncategorized