We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By gillmen wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

–sorta T.S. Eliot

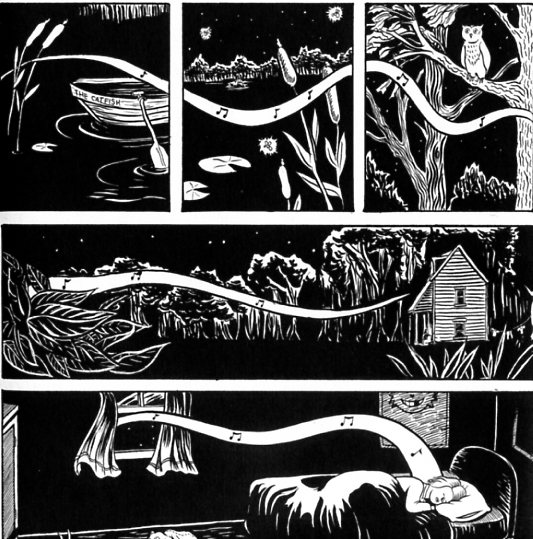

Do you hear that? Off in the distance? A song too beautiful to be real but somehow… familiar? The song twines over the water, through the cattails and the woods, into the window, eighth notes swirling all around. The creature in the lagoon is singing. He’s not dead after all and who are we to resist him and the “centuries of passion pent up in his savage heart?”

Lilli Carré’s The Lagoon (Fantagraphics, 2008) centers on that song and the nameless family who hear it. It’s hard to say what the creature’s motivation is. Revenge? Love? Loneliness? And it’s hard to say what’s going on with the family, but something’s ragged claws scuttle beneath the surface. Maybe it’s the creature. Maybe not. “What was it? Science didn’t know, but dedicated scientists were willing to risk their lives to find out!” a trailer for The Creature from the Black Lagoon exclaims. Though I was dedicated, I never found out the family’s secret, let alone their names.

Carré’s book reads like an epilogue to Universal’s 1950s horror trilogy: The Creature from the Black Lagoon, Revenge of the Creature and The Creature Walks Among Us. With its cinematic, swamp gothic feel, The Lagoon fits with the trilogy’s arc—the gillman provoked in his paradise, displayed in an aquarium and finally operated on by a mad scientist, burning away the outer scales and revealing “a structure of human skin” to make the gillman more human. Now the creature, if it is the same creature*, lives in a swamp near a development.

The Lagoon inverts a couple of The Creature from the Black Lagoon‘s elements. In the film, an explorer drops her cigarette into the water, a Fall from Eden gesture that turns the gillman’s Amazonian paradise into a scientist’s ashtray. In The Lagoon, the creature returns the favor by flicking a still burning butt into a woodpile outside the family’s house. And the creature not only smokes, he has an affair with the woman, who might be one of those women in the movies whose “beauty [had been] a lure to even a Man-Beast from the dawn of time” and led him to be shot, exhibited and experimentally altered. This time, it’s not the Man-Beast who’s lured to his doom. Late at night, the creature sings and people stand in the water listening. Some of them drown.

Carré’s choice to organize a silent medium around sound is an interesting one. She could’ve made a short film. She’s made other ones. Glen Weldon writes that horror comics by their very nature defy a central horror tenet,“The scariest stuff is the stuff you don’t see.” In The Lagoon, the most haunting and seductive song is the one we never hear. We see the song as a series of eighth notes winding through woods, whistled by grandpa or played on the piano by the daughter. But even in a film, the siren song we hear only represents the one that could drown us. Because she’s working in a silent medium, Carré’s never stuck with a siren song’s conventions, which are usually soprano and operatic if sword and sandals movies are anything to go by. A song that lures us to our doom might be an aria, but it could also be something unconventionally beautiful or yearning, something like Tom Waits’ falsetto in “Sea of Love.” In a comic, it can be anything.

After watching Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues, I can’t help but have a vague sense of the creature’s song as a scratchy old jazz record—an instrumental I can almost remember. Something half-heard. Seeing a song visually represented creates the sense of something on the verge of consciousness. And that sense of something half-remembered, half-conceived or half-understood is part of how I think the creature’s song draws people. The family’s humming, whistling, playing the piano, their attempts to recreate the song, maybe understand it, are part of the hook.

Horror like The Creature from the Black Lagoon isn’t just shock, gore and endangered virtue; it’s also about the unknown and the tragic, gradual realization of unbridgeable distance. The creature in The Lagoon is unknown and possibly unknowable to the people who exist beside it. Men listening in the weeds warn the woman’s husband, “Who knows if the creature intended to drown people or if it just wanted someone to sing to and didn’t know any better.”

In one of his philosophical fortune cookies, Wittgenstein says something like, “If a gillman could talk, we couldn’t understand him.” In The Lagoon, that’s the crux of the problem. So, sure, the song is a connection between the creature and the people, but his audience can’t be sure they understand him. The woman has a relationship with the creature, but doesn’t necessarily know how the creature understands that relationship. There is attachment and a song. The creature sings and humans feel. But we never know what song will do us in.

* If it’s not the same creature, the issues would probably be the same: scientific experiments, exhibitions and the inescapable beauty of human ladies, especially white ladies.

~~~

Carol Borden has heard the gillmen singing, each to each / But she does not think they will sing to her.

Categories: Comics

Wow. This is a beautiful article. And I love the links – each one also a gem.

I like the melancholic premise of this “sequel” to the Black Lagoon movies better than Paul Di Fillipo’s recent Black Lagoon novel, which I found actually had too much science and not enough mythic monster, leaving me rather cold.

LikeLike

Hi Carol,

This is lovely.

I appreciate the reference to the cigarette in the woodpile. That scene in the movie, where she flicks her butt into the lagoon and we see it fall above us from under the water, twists my gut. It gets me every time.

sniff . . . why must affairs with monsters always be so melancholy?

LikeLike

I like how the gillmen are integrated into the T.S. Eliot poem. It’s not too much. BTW, the “We have lingered in the chambers of the sea” stanza is my favourite. Nice choice.

LikeLike

Jimi Hendrix called music the last true magic left in the world. Now I know why

LikeLike

Beauty *beatnik snaps*

LikeLike

Thanks, daddy-o.

LikeLike