Prince of Darkness (1987) is not often included among John Carpenter’s greatest films. To be fair, he has a lot of great films. The writer-director-composer-grumpy soundbite generator has clocked an embarrassment of beloved cinema in his time. Halloween (1978), Escape From New York (1981), The Thing (1982), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and They Live (1988) broke molds and defined their era. Meanwhile, Prince of Darkness kind of sank like a stone in the space between action cult classics. It’s not just that it wasn’t a hit; most of Carpenter’s movies weren’t, at least not on initial release. We live in a brutal, unfair world where injustice is rife and The Thing was a box office bomb.

But Prince of Darkness is something else again. Chilly and willfully ugly and weird, it’s arguably harder to sit down with than most of Carpenter’s movies. Not to mention its premise–grad students confront glowing Satanic goo in the basement of an urban Catholic church–is the kind of thing that only sounds fun coming out of Joe Bob Briggs’ mouth. And yet, underappreciated and overshadowed as it may be, I say unto you, Prince of Darkness is no castoff by-blow, some dark, low-budget experiment in the key of Nigel Kneale. It has everything that ever made a John Carpenter movie great, and both in conversation with the rest of his oeuvre and on its own, it’s worth your time. Stalking, secrets, sieges, and synths: Prince of Darkness is John Carpenter all the way down.

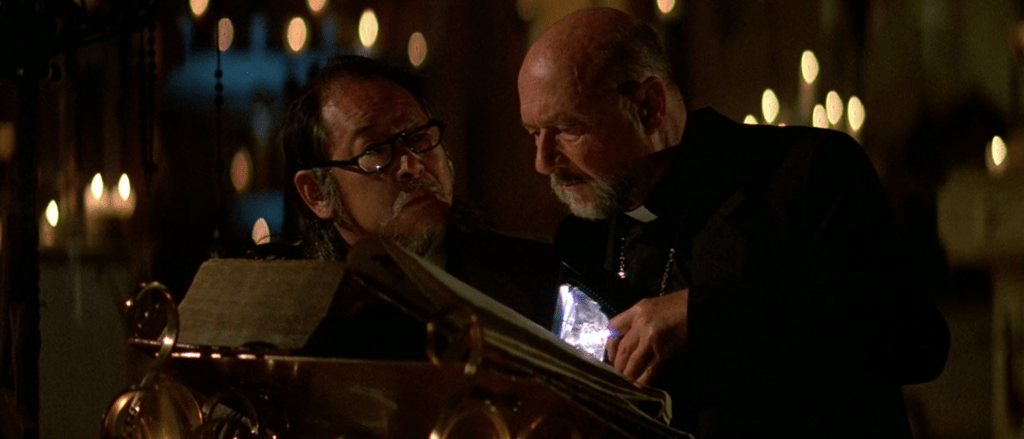

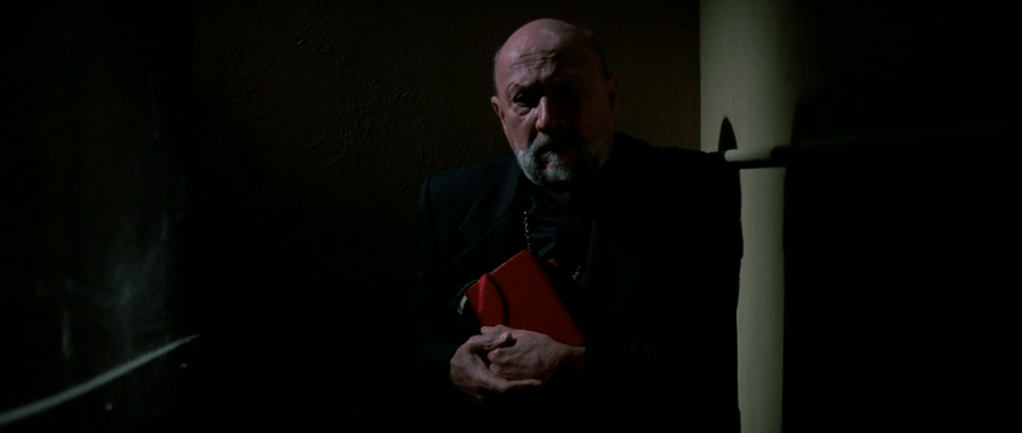

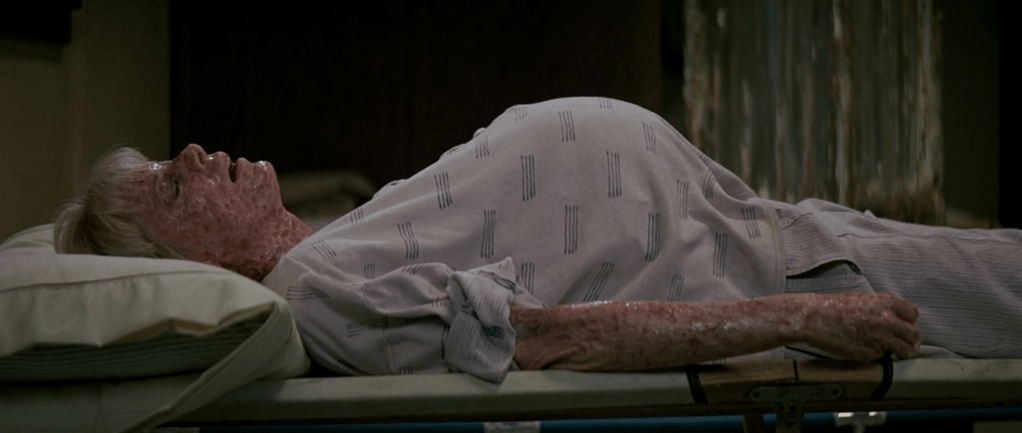

So! [claps hands] The movie gets right to work with a priest in repose, clutching a small treasure chest on what we can infer is his deathbed, at which point another priest inherits the mystery of the chest. The priest, Father Loomis (Donald Pleasence),* does a little detective work himself, tracing the movements of his dead colleague back to a dilapidated, abandoned church in L.A., and what he finds there prompts him to call for the help of skeptic physicist, Prof. Birack (Victor Wong). This is already quite a lot of setup before we’re invited into the candlelit sanctuary beneath the old church, where Loomis shows Birack an ancient volume of palimpsest scriptures and, pride of place on the altar, a large cylinder of glowing green goo.

Of course, it’s evil glowing green goo.

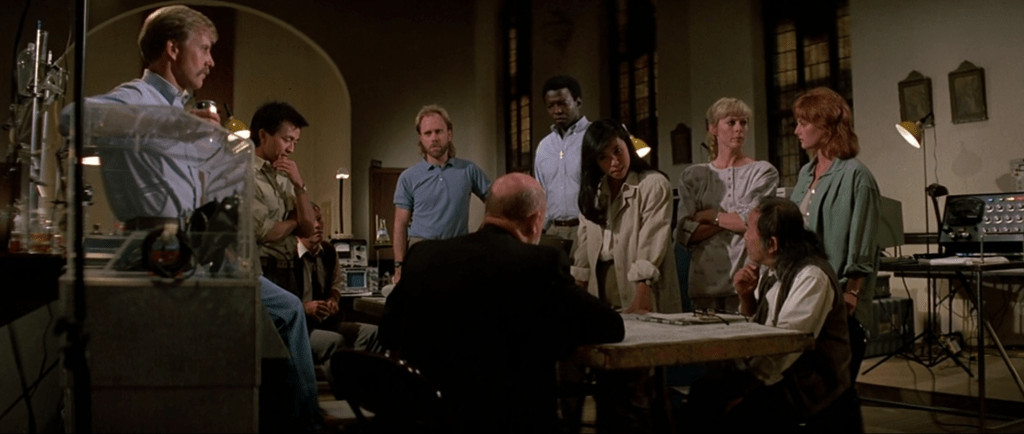

Loomis has Birack conscript his merry band of physics grad students, along with a number of other technical scientist university types, in order to scientifically prove the green goo is, um, bad. Or something like that. The two learned friends, the man of science whose physics lectures sound like Alan Watts clips on Instagram and the doleful priest who might as well be talking about Michael Myers instead of an immobile canister of ooze, mutually commit to science the hell out of this thing. Meanwhile, bugs cluster, worms slither onto the church windows, and Alice Cooper–yes, actually him–leads a group of homeless to stand sentinel around the broken-down church. To Carpenter’s immense credit, he manages to make it all look at once like the end of the world and also any given Tuesday.

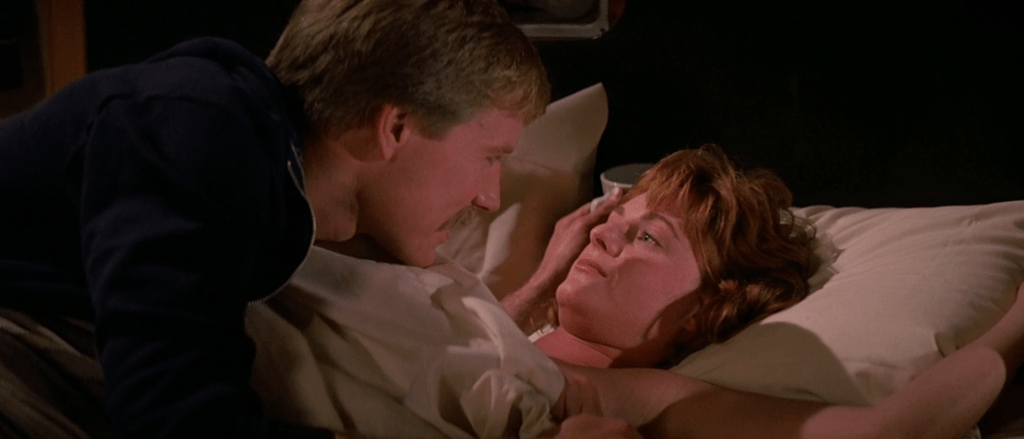

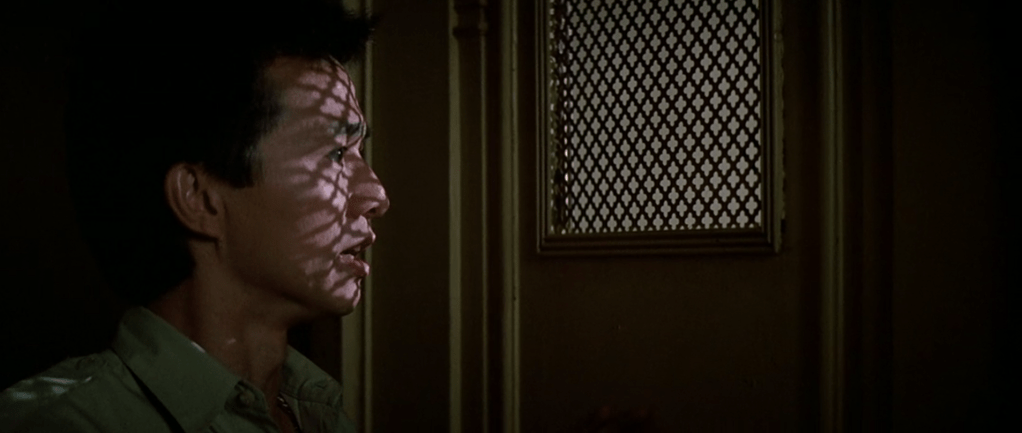

Prof. Birack’s group includes Walter, our loudmouth comic relief who is also maybe a little bit queer-coded; Susan, the one with glasses (take a shot every time someone describes her as wearing glasses and you will be wasted before the final act); Lisa, the one with the magical translation skills of James Spader in Stargate; Kelly, the one who isn’t Lisa or Susan, and finally Brian (Jameson Parker) and Catherine (Lisa Blount), our main characters more or less, competent physicists snared in the first blushes of being squishy for each other.

Speaking of squish, the team moves into the church and things get very The Stone Tape (1972) very quickly, which is also to say they get very The Legend of Hell House (1973) or even The Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) very quickly. It is technology versus the numinous, the unknowable, and of course, the icky. The university physicists’ data-driven approach will mean filling the shambolic inner city house of worship with as many machines that go ping as rudely-fashioned crucifixes, and there are a lot of those.**

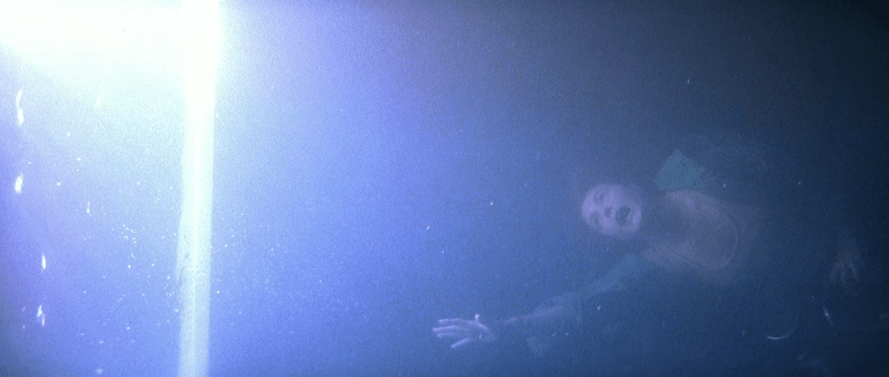

Not that either the machines or the crucifixes prove to be of much use, which is kind of the point, and it’s a beautiful visual, with ancient PCs scrolling equations alongside walls full of Christian symbolism. Carpenter calls Prince of Darkness the second of his Apocalypse Trilogy, smack in the middle of The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness (1994) both of which similarly pit their heroes against cosmic forces they can barely understand, much less defeat. Apocalypse literally means “unveiling,” and that’s what’s going on in all of these films to a greater and greater extent. In The Thing, helicopter pilot MacReady had to accept the existence of a monster that could be anyone or anything. Prince of Darkness ups the scale with a similarly malleable entity that can possess and manipulate on an even wider scale, transgressing bodies, space, and time. And of course, In the Mouth of Madness looses a viral madness on the world that begins with the word…and it is not good. No spoilers, but the unresolved endings of all three movies are important to the point Carpenter is making as well.

Of course, Prince of Darkness is, like so many of Carpenter’s movies, a siege movie at heart. He’s really good at getting a bunch of people together in a creepy, forbidding space and torturing them while the walls close in. Just as in The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness, external forces of cosmic evil bring the body horror and bad dreams. Nowhere is safe, least of all inside you. And the church setting is so well chosen. The broken iron fence on its perimeter is as ragged as rotten teeth, presumably there to protect it, but it also kind of looks like it’s keeping something in. Surrounded by a bleak cityscape, the church could be contemporary or ancient or in the future. Its squalor is timeless. The setting of this film, in fact, is my favorite of his movies, managing to keep our geek squad completely isolated in the middle of one of the most populous cities in the world. And true to form, just like in The Thing and later in In the Mouth of Madness, other people become an appendage of the cosmic horror with the congregation of murderous homeless around the broken facade of the church itself. Monsters taking up residence behind blank human faces is one of Carpenter’s favorite conceits.***

As for the homeless…they are a metaphor, okay? It is tempting, but I will not go off on how the mentally ill are routinely dehumanized in horror, because that is not what is being said. The movie is accessing the instinctive ugh, gross one might feel if accosted by an unwashed stranger, yes, and you can also see this reflected in the way the scientists take notice of the menacing vigil outside their walls. But also the scene where Father Loomis is repulsed when he realizes the woman kissing his hand is also holding a coffee tin of maggots and worms plays on his failings as a priest–and the church’s failings to protect their charges–while being ominous AF. And though Carpenter didn’t write or direct Halloween III: Season of the Witch, Prince of Darkness does seem to refer to it in the framing of the possessed homeless, who line up just like the expressionless assassins in that film, which married technological evils with folk horror to cult classic effect. (He did score Halloween III though, which was also based on a script by Nigel Kneale, who Carpenter sought to honor when he chose Martin Quartermass as his nom de plume for the script of Prince of Darkness.)

I think what might be the most difficult aspect of Prince of Darkness, and also what I really love about it, is how dark and cold it is. That’s true visually, but I mean emotionally. This is some real H.P. We’re Fuckedcraft. Father Loomis suffers a crisis of faith from the very beginning of the film as he delves into his dead colleague’s diaries and comes to realize how the church has consolidated around the concealment of an extraterrestrial enemy of humankind. I’ll forgive you if you shrug at Pleasence’s performance for the first half of the film–it could absolutely be Halloween outtakes–but once Father Loomis hits bottom and digs even deeper to face the real enemy behind the legend of Satan, I dare you to be unmoved. He is so brave, and he is so pathetic, too. We meet Birak in class preaching to his rapt students that reality doesn’t work at all like we assume it does. It might be a brilliant physicist unfolding new theoretical vistas for his class, but in context, for the audience who is aware this is a horror movie and can hear the minor keys being hammered in the background, it’s fatalism. Even the love story between Brian and Catherine feels remote and weird, as we watch Brian low-key stalk Catherine in his first few scenes and Catherine withdraw from him as they start to get serious. Every story, every character, every frame is tinted with dread. And yet, when Prince of Darkness reaches its climax, it will still break your heart, not unlike watching MacReady and Childs share their drink at the end of The Thing while Antarctica burns. In a movie with such a potentially silly Big Bad–the secret of the ooze indeed–the effect shouldn’t be so inescapable, so certain. But it is.

* In the credits, Pleasence’s character is simply identified as “Priest” and this is also true of the shooting script. In the movie subtitles though, the Priest is identified as Father Loomis, and this has given wider credibility throughout the internet to what may well have been a mistake or a fanciful editorial decision in post. I cannot find a reason to substantiate that the character’s name is actually Loomis, which is, of course, also the name of the world’s worst (but my favorite) psychiatrist from Carpenter’s Halloween series. But…Imma respect it anyway. It feels right.

** Who is lighting all those candles?

*** See also: Michael Audrey Myers

~~~

Angela enjoys headcanoning Father Loomis and Dr. Loomis at Christmas dinner.

Morgan Richter has a great video on this film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHGR3AhsaXY

LikeLike