Of all the things to admire about Darr (1993) (trailer)—its uncompromising tension and insistence on menace, the superstar-confirming work by a young Shah Rukh Khan, its creative sequences of characters’ imaginations, the wonderful use of background score—my favorite is how this film disrupts its maker’s own persona. Respected, beloved, prolific director Yash Chopra had never done just one style of film, even though so much of his legacy now is associated with soft, chiffon romances. From the very beginning of his 50-year career, he was interested in ruptures (Dhool Ka Phool, Waqt, Silsila), suspicions (Ittefaq, Aadmi aur Insaan), and identities and duties (Dharmputra, Deewaar, Kaala Patthar, Faasle). But somehow, at least in the spheres of Hindi film discussion I’ve inhabited, the most prominent take on him is that he makes romances. My theory is that this is because the avalanche of charisma of Sridevi, star of the back to back hits Chandni (1989) and Lamhe (1991), buried everyone’s impressions of the decades that came before her, but that’s a different essay. In Darr, his nineteenth movie as director, it seems like Chopra decided to flip the table on his own identity—or at least on audiences’ expectations of filmi love stories, with which he remains so intertwined. Either would be a considerable undertaking, and I think he did both.

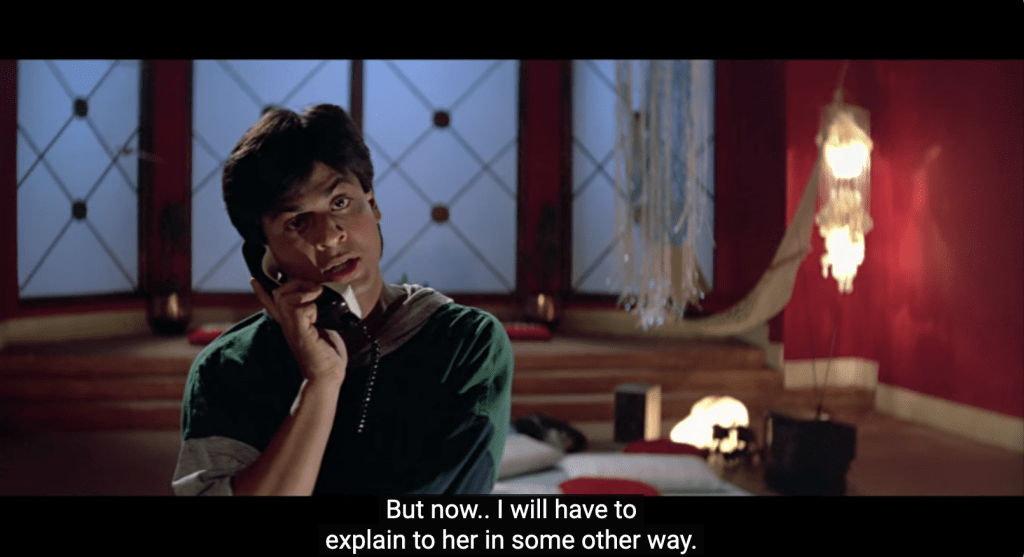

The story of Darr is simple: the obsessive Rahul (Shah Rukh Khan) loves Kiran (Juhi Chawla), even though she is in a relationship with Sunil (Sunny Deol). Rahul has never even really met Kiran, instead secretly watching her and sending anonymous communications that soon spiral into threats. He repeatedly harasses her over the phone, interspersed with phone calls to his mother in which he cheerfully discusses his love and his assessment of what Kiran should do and feel…except his mother is dead, underscoring how very unwell this fascinating young man is.

His father (Dalip Tahil), who is also Sunil’s boss, has no idea what’s going on and just wants Rahul to be normal. Rahul’s intimidation escalates to physical confrontations and chasing Kiran and Sunil to Switzerland. Rahul’s pursuit is consistent, punctuated by comic relief (sigh) in the form of Kiran’s cricket-obsessed brother (Anupam Kher). As Rahul becomes ever more frantic to possess Kiran, Sunil becomes expendable, and everyone finally understands the very real danger Rahul poses.

I love how the movie hints that the hero and villain can be different sides of the same coin. From the onset, they are compared and confused. Kiran thinks a serenade by an unseen singer is from Sunil, but it’s really Rahul. She thinks hands covering her eyes during a black-out at her birthday dinner are her boyfriend’s, but she’s dead wrong.

She thinks Rahul is bursting into her room after one of his terrifying calls, but it’s Sunil visiting unexpectedly. She talks about how much Sunil loves pranks and harassing her, like pretending to be a corpse and falling out of her closet when she opens its door, but she has no idea what Rahul’s harassment is going to mean in her life. As Kiran and Sunil move from engaged to married, the very girlish Kiran struggles to shape a more mature identity, faced with a husband whose eye is already wandering, but Rahul has seen her as sexy all along. What Rahul suffers is not utterly different or separate from the supposedly legitimate and upright love that movie audiences are trained to assume Sunil has. It’s an overreaching, a transgression, a mutation. This is all highly ironic, in a much more fanged way than Bollywood irony tends to be. Here it shows how in conflict with the standard filmi order, how undesirable, Rahul is.

The music is so effective at supporting and creating the film’s moods. Rahul’s theme phrase (the “tu hai meri, Kiran” snippet of “Jaadu Teri Nazar”) is used throughout, repeated and refracted. I particularly like a militaristic version that plays with no instruments but drums that rattle, just as it surely sounds in Rhaul’s head. Or the worried strings as Kiran thinks she’s drowning in a pool (but ha ha, it’s just an unseen Sunil grabbing at her legs. HILARIOUS). Even piercing telephone rings build up the picture, like when the different phone line s in Kiran’s house ring simultaneously but discordantly.

Along with Chopra, writers Honey Irani (who did Lamhe and the bloated family saga Parampara with Chopra) and Javed Siddiqui (who also worked on Baazigar, the other essential villain turn by Shah Rukh Khan) undo so much of what we thought we knew to be universal film truths. In Darr the hero still wins, but barely, and significantly here it’s not because he has less power or fewer resources than the villain. Quite the opposite: Sunil, the Navy commando who defeats boatloads of terrorists, should have easily defeated the smaller, less experienced, less formally trained, and wildly less healthy Rahul. But he doesn’t. Rahul almost wins, even escaping Sunil in my vote for Hindi cinema’s very best chase scene, even though no one in the film wants him to. You can almost imagine that if his mother had been alive, she might still blindly be in his corner, in the grand tradition of filmi mas, but he doesn’t even have that.

No energy is wasted on showing the psychopath’s slow descent into madness. Introduced as a peeping-Tom’s-eye-view of the wet and vulnerable heroine, an uneven, distant percussive sound under the melody that will become his calling card, a rustle in the forest, we know he’s a threat before we even see him. That is brilliant. And when we do first see more than his hand, he is quite literally already on the edge of death.

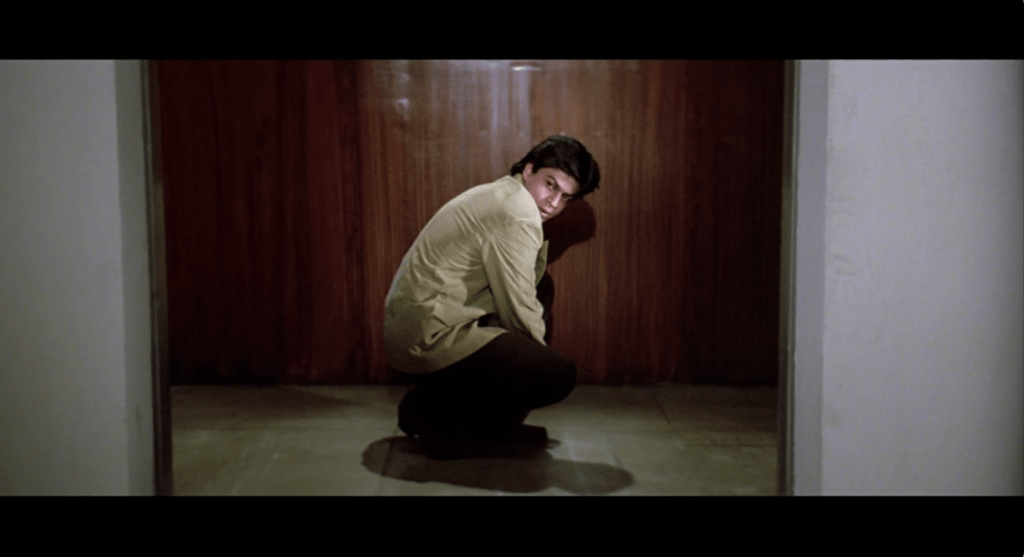

Not just the scenarios and dialogue but also so much of his basic posture and blocking added to our sense of who Rahul is and what he’s thinking. The first time we see an identifiable Rahul and Kiran in the same physical space, in the span of a few seconds he goes from sniffing an unwitting Kiran’s clothes and almost touching her to curling up in a little ball in when Sunil appears. He expands, he contracts, like a beating heart. It’s perfectly depicted.

This is a person who is not yet confident (or maybe unhinged) enough to be seen. Later in the story, he will crash right past simply being visible to flaunting his presence, but not just yet. Rahul’s mania takes many forms: he can relax and play with it, but he can also be wound up and pushed over the brink by it. Rahul is a dishonorable person who breaks the rules of acceptable behavior both in the society of the story and as a type of character, and yet he is completely compelling.

These pieces come together into a frankly shocking reality: has a mainstream Hindi film ever more effectively threatened its own romantic love? This threat is not just about what’s happening in this film: it’s a threat to how narratives work and to what audiences think films will be about. Darr sows radical seeds by refusing to obey the formulas we know and love. It’s possible that not even the expert Chopra could have predicted that relative newcomer Shah Rukh Khan would inhabit Rahul so achingly and so charismatically that audiences couldn’t help but love him. Certainly the script as we see it on screen loves Rahul, giving him every opportunity to retract, confess, and reform, a pitiable motherless child whose military father doesn’t even try to understand him. In concert with the career-making performance of the villain, there’s the problem of—and hear my finger quotes—”the hero.” Sunil is just…a jerk. A haughty, paternalistic, useless jerk, who loves to physically scare his girlfriend even after he knows she’s being stalked, lending grudging credence to Rahul’s insistence that Sunil doesn’t deserve Kiran. There’s never any overt suggestion that Rahul is a better romantic choice than Sunil, of course, but I’m surprised just how frequently Darr depicts Sunil as less than ideal himself.

A few minutes into the film, Kiran sits on a speeding train that plunges into a dark tunnel and narration booms over the credits. The voice tells us that love can cross into devotion and then obsession, which has been seen in countless other classic stories. But this story is different. “It also has one more element…something which has not featured in any love story so far. Fear.” The absolutely expert Chopra grips us with that fear for almost 3 hours straight through, cranking it up constantly until all three lead characters have bubbled over, taking us with them, yanking away the safety blanket of the love story formula and leaving us cheering for a sociopath. The threat Chopra extends via Rahul is not just about what’s happening in this film: it’s a threat to how narratives work and to what audiences think films will be about. Thirty years after its release, Darr remains upsetting and unsettling in all the right ways.

Darr is available with English subtitles on Amazon Prime and to rent on Youtube/Google Play and Apple.

~~~

The Gutter’s own Beth Watkins remains unsettling in all the right ways.

Categories: Screen