When I was eight years old, my mother showed me a stuttering laserdisc version of Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) and changed my life. (Good one, Mom.) Formerly a fraidy cat, I fell in love–with Dracula, with horror, with Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó Lugosi. I also fell in love with Dwight Frye a little bit, but that’s a story for another time, and it was Lugosi who became my first earnest, eternal obsession. He still is. But my admiration is but a drop in an ocean of blood. Just how many Monster Kids (née children of the night) did Lugosi Turn from the other side of the screen for decades, decades, decades after his own death? How many yet and yet unborn?

This month, I want to celebrate Lugosi 93 years after the Valentine’s Day release of Dracula with two brilliant graphic novels that draw on his legacy: Legendary Comics’ retelling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Koren Shadmi’s Lugosi: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Dracula–books of great artistry and merit in their own right, but revelatory of different sides of the same coin. Because every story about Lugosi is a story about Dracula, and at least since 1931, every story about Dracula is Lugosi’s story, too.

But how can I say that, in a world with Coppola’s Dracula and Castlevania and Johnny Alucard? Simply because every screen Dracula, even if they reject Lugosi’s performance and accouterments, will nonetheless find his shadow falling across their script pages. He is beyond iconic, beyond memetic. He is breakfast cereal and a muppet. But more than just this trans-generational ubiquity of Lugosi’s fragmented image and his distinctive voice, the success of Lugosi in Tod Browning’s thinned version of Bram Stoker’s novel, based on the Broadway play Lugosi starred in, has crowded out a majority of Stoker’s text, to the point that attempting to reproduce it faithfully marks a departure from the story everyone expects. (I will here direct you, however, to the Gutter’s own Carol’s definitive piece on Draculas, Lugosi and non-Lugosi.)

In 2020, Legendary Comics attempted to correct this divestiture of Dracula stories and, with the blessing of the always protective Lugosi estate, deliberately crossed the streams with Bram Stoker’s Dracula: Starring Bela Lugosi. The graphic novel purports to reconstruct Stoker’s text with Lugosi’s famous face, and it does. It works, and not just by casting Lugosi. I would hasten to mark out how well the adaptation suits the medium more generally, with Robert Napton’s narrative choices–moving Carfax Abbey to Whitby or dramatizing the Count escaping the wreck of the Demeter as a wolf–hastening Stoker’s epistolary novel along toward its most cinematic moments. I confess I have a love/hate relationship to Stoker’s text that goes back nearly as far as my love of Lugosi, wanting to take razors to secondary characters and whole chapters, much as every Dracula adaptation has done because it’s just so much, and up until now, my favorite version was the unauthorized Turkish adaptation by Ali Riza Seyfioglu, Kazıklı Voyvoda. Here, Napton negotiates with Stoker’s novel in better faith than even Seyfioglu, admirably preserving its flavor and its large cast while privileging its greatest set pieces–Harker’s imprisonment, the wreck of the Demeter, Lucy Westenra’s seduction and death, Renfield’s betrayal, and the final globetrotting game of whack-a-Drac undertaken by our stalwart heroes–and still leaving plenty of room for the art to render the story.

And the art in this graphic novel is choice. It is, after all, the reason we are here: to see what we have never seen but already know, and it surpasses my imagination. I cannot discuss it as thoughtfully as our own comics expert Carol, but this is some of the most beautiful, fluid, dynamic art I have ever seen in a comic, invigorating the familiar story and the less familiar bits that perhaps could not be retained for a film adaptation for want of time or technology or censors and all in glorious black-and-white. I appreciate also that El Garing’s meticulous, yet idealized portraiture takes advantage of how we know Lugosi aged to depict the Count at different stages of his un-Life. The Count we first encounter is, unlike the charismatic 46-year-old we met in Dracula (1931), much more the dissipated, aged Lugosi of Ed Wood’s poverty row features, and later, as Van Helsing describes the voivode prince’s history, we will see a Lugosi Dracula he never got to play, armor, ponytail, and all, but as well-fed and smooth as in his film debut.

There is something sacrificed, however, in unifying the two progenitor Draculas, like a lost memory regained–Dracula isn’t onstage a lot in this story. I think this is as forward-moving and seamless as the action in a Stoker adaptation gets, and we do enjoy scenes demonstrating Dracula’s awful powers of compulsion, transformation, and bloodsucking that Tod Browning never could have realized and aren’t depicted in the novel either, with gore and decollete to spare. This Lugosi Dracula actually has fangs. But any faithful rendering of Bram Stoker’s story is going to really be about the good upright men and one very special woman who repel the nasty revenant creature from Old Europe, making this Dracula actually have fewer lines and less of a personality than Bela’s original. Now he’s a lot more like the hissing, feasting version made famous by Christopher Lee, and Bela might not have liked that.

It’s still really cool to actually see him vamp out though.

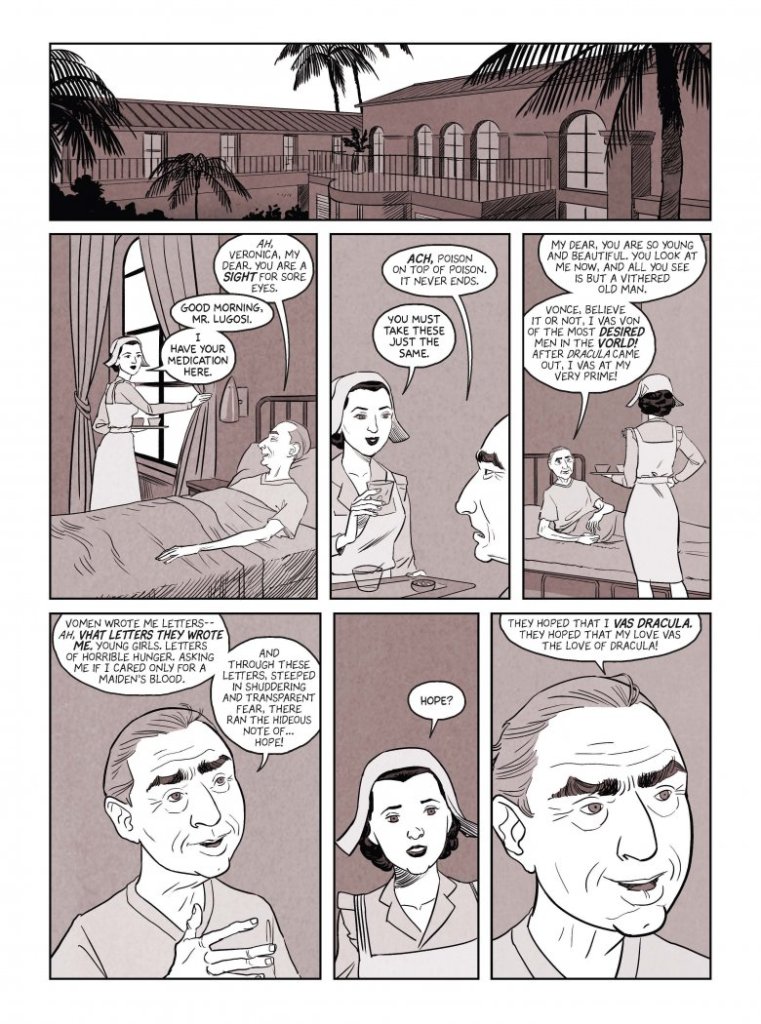

Another story that has survived Lugosi, another story everyone expects, is the actor’s pitiable downfall from the heights of celebrity to the gutters of poverty row. It’s funny, in a not-at-all funny way, how his tragedy mirrors the story of Edgar Allan Poe–in his multiple, ill-starred romances, in his poverty and addiction, and in the mythic sacrifice of the artist to a craft that will only be truly applauded after he is dead–when all of his Poe films were Poe stories only in name. But so many artists travel that sorry road. It is a wonder we ever want to hear it retold. But we do, and in Koren Shadmi’s Lugosi: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Dracula, we get an affectionate, but not flattering, retelling of Lugosi’s life, beginning near the end, with Lugosi’s voluntary commitment to a hospital to fight a decade-long morphine addiction.

Lugosi’s talk with a nurse segues naturally into a reminiscence of his youth and his conflicts with his banker father over becoming an actor, running away after his mother blames him for his father’s death, realizing his dreams in fits and starts during the turbulent revolutionary fever roiling through Hungary and its surrounding countries in Lugosi’s young adulthood. We witness his thwarted first marriage, his adoption of socialist ideals and the price he pays for them, and eventually his landing in the U.S. There’s nothing about his time in the Hungarian ski patrol in World War I, which is a strange omission, although I am favorably impressed by the completeness of Shadmi’s biography in other respects and also the way he makes clear the many stories about Lugosi’s life often only have him to testify to–and Lugosi’s life story changes a lot on his own lips.

It is always so striking to me how quickly films were turned around in the 30s and, relatedly, how fast studios burned through their stars, and this was more true of Lugosi than most. The studios didn’t envision a lot else for the heavily accented and aging Lugosi to do but horror pieces, and horror was on the way out by 1934, hastened by the Hays Code, censorship in Britain, and of course the waning popular appetite after being glutted with so much fresh meat on the theme every couple months (ahem, Marvel, Star Wars, ahem). This is the key tragedy of Lugosi’s life, overshadowing his infidelities, his failed marriages, his exile from his true and natural homeland in Hollywood. Shadmi plays this period of Lugosi’s life like a lonesome cello, although much as in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, the song is strangely joyful due to Bela’s insistence on dreaming and celebrating his own talent, especially when the world was not buying it. If Shadmi’s art style is more cartoonish than realistic, Shadmi’s recreation of key moments from Lugosi’s films are as moving as the visual feasts in the Legendary Comics’ Dracula, and reading these books near to each other makes these verbatim outtakes even more satisfying. I do appreciate that Shadmi doesn’t shy away from showing Bela be a bit of a bastard, too, especially to Lillian, his long-suffering wife taken virtually as a child bride and the mother of his only child. “Poor Bela,” Karloff once said of his screen nemesis, and this is the inevitable arc of any Lugosi biography. It is terrible that Bela’s career never had the second life that Karloff’s got, but I like that Shadmi spends enough time with Bela’s personal life to show he wasn’t the only one suffering for his art.

I don’t believe personalities survive death, but I would like to, if only I could believe Lugosi had a way to see how much his Dracula still matters. Of course his son has lived to see it, and to see it codified into law (see Lugosi v. Universal and the California Celebrities Rights Act), though Lugosi’s Dracula will still pass into the public domain in 2026. Free fair use of his likeness in that case will probably only amplify how much his Dracula is still the Dracula of record,* and how it has kept his own story alive in all its penury and sordidness and brillance, too. Bela himself said it best: “No, no. Dracula never ends.” Dracula is still a relatively young monster all told, born in 1897, but I would wager Bela was right and thousands of years from now, some version of Dracula will still exist, probably scaring and seducing whatever biomechanoid Cronenbergian form of life is dominant with his fleshy deathlessness. But as long as Dracula lives, so then will the best of Bela Lugosi, immortal and beloved, forever. Happy Valentine’s Day.

*Don’t come at me Lee/Langella/Oldman fans, I love them, too, and Jourdan and Palance and pretty much anyone but Claes Bang.)

~~~

Angela is currently jamming to Lesbian Bed Death’s “Bela Lugosi’s Back,” only her third favorite song written about him. Points to anyone who can guess the other two.

Wonderful

LikeLike

This is a wonderful, lovely piece, Angela. (And thank you for the overly kind mentions!)

LikeLike