Every winter, I have the urge to burrow into British ghost stories, but not so much Dickens as M. R. James. And once I have watched the latest BBC Ghost Story For Christmas, I re-watch older stories or seek out new-to-me shows and movies in the same vein until I inevitably venture back into one of my favorite genres, British folk horror.* This year, just before the Winter Solstice, I came across a recommendation for Rabbit Trap (UK/USA, 2025) and I am so glad I took it.

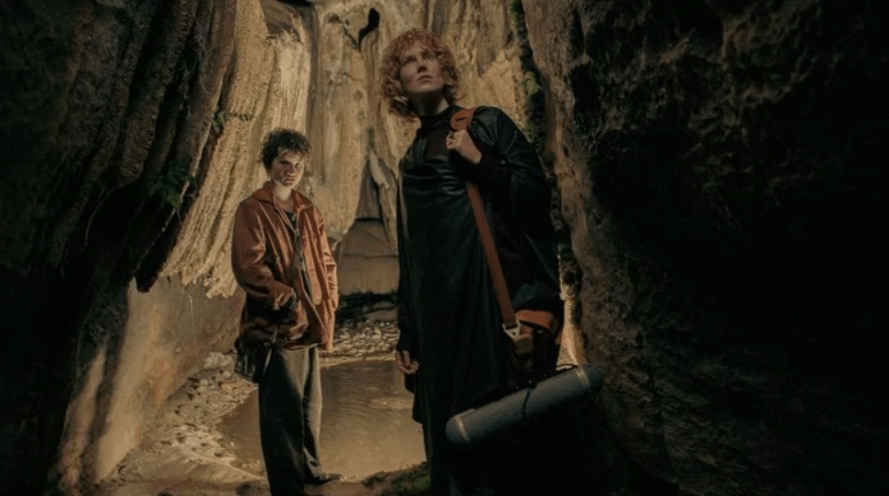

Rabbit Trap is a film as folk tale. A couple, experimental electronic musician, Daphne Davenport (Rosy McEwen) and her sound engineer husband, Darcy (Dev Patel), go into the wilds of Wales and pass through the veil into a liminal world. There they encounter a child who is not a child and a sound that is more than a sound.

From here on, I discuss the film in depth.

With its opening narration over soundwave imaging (paralleling chattering, flocking birds), Rabbit Trap reminds me of The Stone Tape, both Nigel Kneale’s 1972 original and Mark Gatiss’s 2022 BBC Radio 4 adaptation, which features binaural sound design by filmmaker Peter Strickland. Rabbit Trap‘s soundtrack was created by composer Lucrecia Dalt and sound designer Graham Reznick—with some riffing by Rosy McEwen as Daphne.

Discussing the sound of the film, writer/director Bryn Chainey says:

[Dalt] composed a lot of the music before we shot. That was important. All using instruments up until 1976. She went to different museums and different studios to use their gear, and she composed pieces that Rosy, on set, could play along to, so we needed those things composed before the shoot. The sound design was by a guy called Graham Reznick….So those two were really working in collaboration with each other, sending things back and forth.

Like the BBC Radio adaptation of The Stone Tape, Rabbit Trap might best be watched with headphones, if you can’t see it in the theater. As Daphne says, “With your eyes, you enter the world. With your ears, the world enters you.”

There are echoes of other foundational British folk horror—The Owl Service (1969-1970), also set in Wales and dealing with Welsh folklore; Penda’s Fen (1974); and, Robin Redbreast (1970). In all three, as in Rabbit Trap, outsiders, usually English outsiders, travel to places where the old things of the land still have a hold and can draw the unwitting into their world, their stories, and their music. Set in 1976, the events of Rabbit Trap occur after all these stories, but could be happening in their world and perhaps in ours. Who knows what sleeps in the shadow and soil of the wild places? Who knows what sounds would lure us into the Other World? Who knows what music we make that would draw them into ours? And what musicians would not be tempted to hear the music of faerie itself and record it?

Despite our desire to escape the pain of our own world, to live in a beautiful world of endless music, folklore suggests we cannot survive it. And that the Good Family, the fairies and goblins, the changelings and the snatched children who find their way back, do not understand or, caught up in their own desires and needs, do not care that they can break us.

Daphne and her husband, Darcy, take a house in rural Wales to record new music for an upcoming album and, it is strongly implied, to recover from a miscarriage. A woman working in an experimental musical form, Daphne, though renowned among a small circle of enthusiasts, is already marginal before she comes to Wales. Darcy suffers night terrors that suggest he was a victim of sexual abuse. He apologizes for them, but, feeling irredeemably tainted, lies to Daphne about remembering his dreams. His response is to love Daphne fiercely and quietly, caring for her, but not asking for care. Darcy travels the hills and woods recording natural sounds for her compositions. In the forest, Darcy encounters a strange sound causing weird vibrations in a pool of water. He follows the sound to its source, a ring of toadstools and records it. Daphne is enthralled by his recording and begins riffing on it with her equipment. They are enchanted.

The sounds Darcy records and the music Daphne makes are not the sounds and music used in so much fantasy to depict the Fair Folk and wondrous encounters with the Other World. It is not sparkling chimes or sweet strings. There are no harps or pipes. There’s no Enya. It is deep and strange, sometimes howlingly chthonic and sometimes a garbled electronic transmission. And the music Daphne makes would never grace a Renaissance Faire. Chainey notes in interviews that it was inspired by the work of pioneering experimental electronic musicians Delia Derbyshire, Suzanne Cianni, Laurie Spiegel and Daphne Oram.

Daphne’s music attracts the attention of a child (Jade Croot) who startles Darcy as he sits on the moor outside the house while Daphne riffs on the sound—warping, distorting, building on it with her equipment. Darcy is alarmed by the boy’s sudden appearance, but the child says, “Shouldn’t I be afraid of you?” The boy had been out hunting rabbits and takes Darcy to see how he does it. He says:

If you want to trap a rabbit or any creature, you need to know what it’s hungry for. And that’s what you offer as a gift. And you have to mean it. Then you just wait for the rabbit to be hungry and he traps himself.

When the boy visits Daphne the next day, he tells her:

Rabbits are special because they move between worlds. But they live underground in burrows, warrens, in the dark places. They come up and go down with the sun, passing messages between here and the underworld. And if you catch a rabbit, you catch the message it is carrying.

Rabbits are liminal beings—messengers, shapeshifters, tricksters. Even now, at the beginning of each month, some murmur, “Rabbit, Rabbit” for good luck. Rabbits are wise and they are trouble. And the whole point of so much British folklore, is that these things that were supposedly banished by religion, reason, and civilization, are still here. Perhaps sleeping curled up like rabbits in their warrens, perhaps hiding as the boy does among the grasses and rocks of the moor, along the edges of our society. And human music is always a lure for these beings, the Welsh Tylwyth Teg, the Good Family, the faeries.

Played by Jade Croot, an adult woman, the boy is liminal himself. He is plausibly a free range tween or teen of the 1970s, but he never shares a name or where he goes after leaving Daphne and Darcy. He is a child who has lost at least a brother and a mother who died so long ago he can’t remember her face. I still haven’t settled on how I feel about the child being played by an adult woman, but there is no denying the primal power of Croot’s performance. I do think that it gives the boy a slight uncanny agelessness that is in accord with someone or something that is not who he seems—something that might be taking the form of a human boy desperate for parental love. And Croot playing the boy is eerie, without leaning on negative stereotypes about nonbinary, genderqueer and agender people.

The child tries to weave himself into the couple’s lives. He brings them gifts from the land. He shares what he knows of nature. He tells them the gorse surrounding their cottage means that the previous occupants had trouble with the Good Family. He shows them secret places. He gives them a rabbit he caught and is devastated when he feels the rabbit’s death is wasted because Darcy doesn’t know how to skin it. After Darcy tries to send him away one morning, the boy frantically begins demanding Daphne. He takes Daphne to hear the song of the Widows of the Wood. Darcy follows and becomes lost beneath them. The boy tries to convince Darcy that he should stay lost:

You’re rotting and she’s rotting with you. Don’t let it spread. Stay with me here, beneath the blankets of shadow and soil and secret.

The boy wants a family, a home and a name. Darcy interfered with that and so the boy tries to get rid of him. After their journey, the boy calls Daphne, “Mam.” He asks to be let into their house. He asks her for milk. He takes a bath in their home. He asks for food–an inversion of his gift of a rabbit intended to feed them, to make them and have a claim to them. It was a different kind of rabbit trap. He asks for a kiss good-night. He asks to be named. And he will not leave the house. “We’re family, see? You clothed me. You fed me. You bathed me,” he tells Daphne, implying these actions are a pact. The boy uses all the magic words and rituals of childhood to will a family into being for himself.

And when Daphne and Darcy drag him from their house and refuse him a name, he burns the gorse surrounding their home to let the Tylwyth Teg in. The next morning, the boy wakes Daphne and Darcy as they lay beneath a mossy blanket in a bed half-claimed by nature. He tells Daphne he had a bad dream that she didn’t want him.

It could have ended there with a threatening, powerful child demanding adults accede to their desires. It certainly does in much horror. But as in so many folktales, Daphne and Darcy are clever. Their only way through—their only way to survive and heal—is to give the child and each other what they want and mean it. It’s unclear at first that the couple has a plan. They might be trapped and acting out of fear. There might be some kind of glamor compelling them. I appreciated the tension of these uncertain moments. But even before the film reminds us what the boy had said about catching rabbits, it’s clear from looks and small gestures that Daphne and Darcy are afraid, but they know what they are doing. They are enacting a family life and they mean it, but doing so to escape the boy’s trap and catch him instead. Daphne, Darcy and the boy spend a day as a family. And at the end of the day, they tell the boy a bedtime story about a rabbit who is afraid of the dark and his friend the wise, old bat who helps him with his fear. They tell him into their story, as the boy had tried to tell them into his story of a family and a home. And the boy begins to speak for the rabbit. Stories work as the revelation of truth, but also as spells. Like music and sound, stories can shape reality.

One thing that differentiates Rabbit Trap from much 1970s British folk horror, is that Daphne, in particular, escapes the trap. I appreciate that. I like the ending and I like Daphne and Darcy’s relationship. McEwen and Patel have excellent chemistry and present a couple that cares deeply for each other. I like that they give the child what he wants, mean it, and pass through this liminal space together.

Still, Rabbit Trap is a wonderful evocation of 1970s British folk horror. The period elements are perfectly done from the vintage equipment and Daphne’s rings and velvet coat, to the unhurried pacing and grainy look of the film. And Rabbit Trap looks wonderful. It uses the whole screen, which I appreciate more and more as franchise films focus on standard coverage, alternating close-ups, bland lighting, and limited palettes. Despite its emphasis on sound, Rabbit Trap is incredibly tactile. The immediacy of the sensory experience reminds me of both Charlotte Colbert’s She Will (UK, 2022) and the films of Peter Strickland. I could almost feel the moss and the wet rocks myself. The audio equipment is shot with the same care and affection as mosses, stone fields, flocking birds, pools of water, and snails.

Rabbit Trap joins more recent folk horror focused on faeries, particularly three Irish films. In Paul Duane’s All You Need Is Death (Ireland, 2023), a folk song might be cursed—or it might be a cage that holds something old, a god or Aos Sí. And in this context, I do wonder about the otherworldly sound Darcy records.** I wonder if I hear the boy’s voice in it and what that might mean. Are they hearing the past? The future? Is the boy calling someone—anyone—them? In Aislinn Clark’s Fréwaka (Ireland, 2024), the Good Folk are drawn to the sound of revelry at a wedding reception and take a pregnant bride. And they spend decades trying to come into a woman’s home. In Kate Dolan’s You Are Not My Mother (Ireland, 2022), the story is reversed, with a changeling mother coming to claim “her” daughter.

Rabbit Trap is clear about the power of music and sound, the power of names and stories in summoning and defining beings. But it is not explicit about what exactly the boy is. And I appreciate the film’s embrace of ambiguity. The child could have been taken by the Tylwyth Teg. When he tells them of his brother taken long ago, he could be speaking of himself. He could be a boy who wandered into the other world so long ago that he has forgotten his mother’s face. He could be a one of the Tylwyth Teg who wants to become human, to be loved and cared for as a child. He could be a changeling for a child Darcy and Daphne didn’t have the chance to raise. Perhaps the boy is a ghost returned to the living world. He might be a rabbit who has become a human—with perhaps a rabbit brother. Or perhaps, again, he himself is the brother who wandered into a fairy circle only to “swell up like a toad” and grow much too fast into a human boy. Then he becomes a rabbit again when Daphne and Darcy tell him the story of himself.

I have my own shifting opinions about the child’s nature. Today I think he is a boy taken long, long ago, who followed Daphne’s music back. But in a previous viewing I thought he was one of the Tylwyth Teg and considered whether he was a rabbit or a púca / pooka. With my own changeable nature, I will likely have a different opinion tomorrow.

Listen to Lucrecia Dalt’s Rabbit Trap soundtrack on Bandcamp or YouTube.

*Not The Wicker Man (1973), though. I watch The Wicker Man in May, as Lord Summerisle intended.

** Chainey has some interesting comments on the sound in an interview at Variety: “With analog electronic music, they’re not sampling sounds, there’s actual electricity running directly through their oscillators and they’re changing the frequency and the current to make a sound. And I thought: that’s fertile ground for a cosmic horror, because you’re taking the energy from the earth and twisting it to create sound. So what if you did that in a landscape that was haunted and had spirits living under the earth? That was a big reason why I made the characters electronic musicians, because it linked them to the landscape and Welsh folklore. You cannot separate goblins from music. They’re always singing – you’re lured by their music!”

~~~

Carol Borden might be a goblin, but not that kind of goblin.

I’m so glad you poked at me to see this because you’re right; it feels like a film custom ordered for me! So many obsessions wrapped in a glorious moss coat with resonant soundtrack. Beautiful writing here. My situation not ideal for watching: traffic noise, dripping ice, clicking heating through the pipes and yet somehow that ended up adding to the texture of it. I need this film, soundtrack and many more musing on liminal fae sound.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s wonderful and I am so glad!

LikeLike