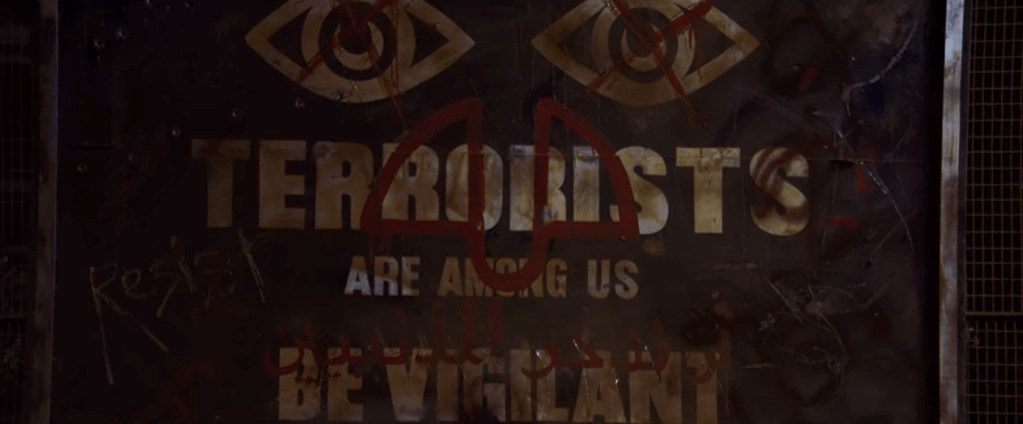

Ghoul (2018) is as bleak as might be expected for a series that starts with the line, “Strike a deal with your blood and out of the smokeless fire the ghul will come.” It’s a three episode miniseries that addresses fascism, state terror, and individual guilt in a dystopian near future India. The “scheduled religions,” mostly Muslims, live in restricted zones and the state encourages people to turn in “anti-national terrorists”–even family members. The cruelty and injustices gnaw on people, consuming them. It was only a matter of time before a monster was summoned to reveal the monstrousness all around.

In the first episode, before the title appears, a prisoner strikes a deal with their blood, drawing a symbol on the concrete floor of their cell. Then we shift to a month earlier as Shahwanaz Rahim (S. M. Zaheer) drives his daughter Nida (Radhika Apte) back to the National Protection Squad Academy where Nida is training. Mr. Rahim lives in a Scheduled Religions Zone, a pointed reference to India’s “scheduled castes” and “scheduled tribes,” and they are stopped at a checkpoint. Nida’s father is frightened, not only because of the soldiers’ capriciousness, but there are there forbidden books in his car, along with his lecture notes–proof that he has been teaching his students things not on the government’s approved syllabus. This alone could get him labeled as an anti-national terrorist. When the soldiers are about to begin a search, Nida intervenes using her NPS ID to stop the search and save her father. But as she looks at him, Nida begins to see him as an unwitting anti-national terrorist as described by Lt. Col. Sunil Dacunha (Manav Kaul) at the Academy. While she is a devout Muslim, Nida believes what she has been taught about the benevolent state beset by enemies. She believes that the laws and re-education are not targeting people specifically for their religion, but that the enemies of the state who are Muslims are not true Muslims. Patriotic and naive, Nida turns her father in to the police, believing he will be re-educated and sent home once he understands the truth.

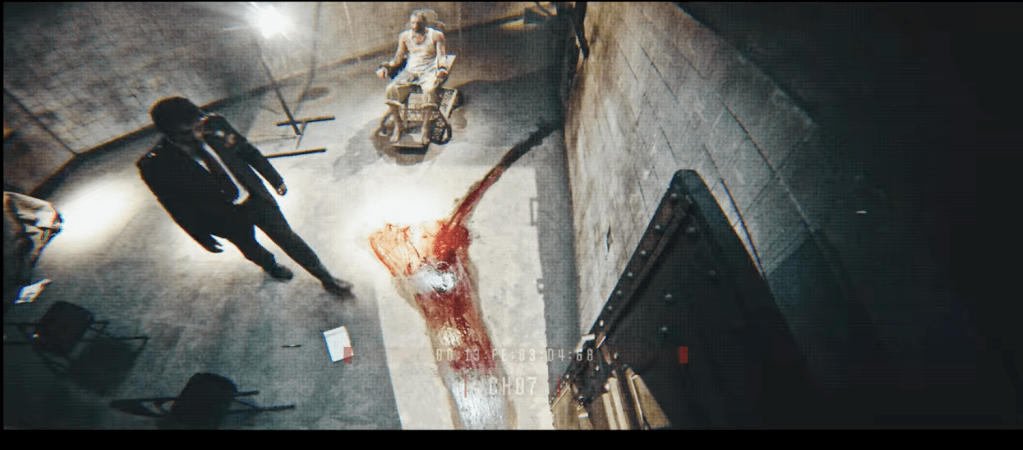

Nida is assigned to a black site, Meghdoot 31, to interrogate detainees under the orders of Col. Dacunha. She is met with suspicion by the venomous and definitely untrustworthy, Major Laxmi Das, wonderfully performed by Ratnabali Bhattacharjee. It turns out that a high profile prisoner and leader of one of the most active anti-government organizations, Ali Saeed (Mahesh Balraj), mentioned her name. But Saeed is dead and what sits in the site’s interrogation room is a ghoul summoned to reveal the interrogators’ and the prisoners’ terrible secrets before killing them. And once it has consumed someone’s flesh or blood, the ghoul can take on that person’s form.

Released on Netflix, Ghoul is a co-production between the now defunct Phantom Films, Ivanhoe Pictures and Blumhouse Television. It has a bit of Blumhouse feel. But it is more interesting to me that Ghoul is one of three Indian co-productions with Anurag Kashyap’s Phantom Films, including: Sacred Games, a neo-noir based on Vikram Chandra’s 2006 novel, and, Lust Stories (2018), a sort of sequel to Kashyap’s anthology, Bombay Talkies (2013). You might recognize Kashyap from his two part Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) or his recent science fiction thriller, Dobaaraa (2022), a remake of Oriol Paulo’s Mirage (2018). Kashyap co-produced and co-directed Sacred Games with Vikramaditya Motwane and directed a segment of Lust Stories. With Ghoul, though, Kashyap doesn’t direct. Instead British citizen / Indian resident Patrick Graham wrote and directed the series. And Radhika Apte has roles in all three projects. A lot of people are rightfully annoyed with Netflix, but I do appreciate Netflix’s making interesting international projects happen and making international series more available in North America, especially ones that could not be widely shown or shown at all in their home countries.

Ghoul reminds me of character-building, citizenship-conscious dystopian movies I was shown in school–things like The Lottery (1969) and Fahrenheit 451 (1966). Movies that warned us of the damage we can do in groups. The Ghoul is critical of authoritarianism, nationalism, Fascism, Hindutva, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and is sympathetic to outcasts, intellectuals and scapegoats. I felt a lot of resonance not only with what is going on in India, but what is unfortunately going on in the rest of the world and in America. There was a time that Ghoul would have seemed heavy handed to me, but, well, here we are. Authoritarianism and cruelty is everywhere. So maybe we need more stories that show us what we have wrought all over the world.

Ghoul does illustrate how at least some people become part of such a system of cruelty. Dacunha considers himself a hero acting within the law to protect his nation and exterminate its enemies. He implicitly sees his heroic work now as a continuation of his ancestors’ work defending the Catholic Church during the Portuguese Inquisition in India. Nida is a well-meaning person who believes in justice buying into an authoritarian system that twists everything to serve its ends. While Major Das is illustrative of a woman who buys into the system more than the men around her not only because she enjoys her work, but because it is a source of power and respect the major would not have otherwise in this very system.

But what struck me even more was the revelation of their guilt–how it was revealed and the importance of its revelation. As Ali Saeed sits in the interrogation room, he hints at monstrous things his torturers have done and inverts their interrogations. Instead of telling the story that his torturers want to hear–the one that reinforces the existence of a shadowy enemy, the necessity of disappearances and torture, the need for a fascist state–he tells them the truth, their truth. The ghoul whispers their secrets. He reveals to them and anyone listening that they are murderers, liars, betrayers, deluded, failed husbands and failed fathers. Driven to conceal their guilt, they beat him and try to kill him. But this demon that looks like Saeed does not die and so the truth does not die. And once the ghoul consumes a piece of them, even with just a bite on the calf, it can become anyone. He takes on the face of another and continues to whisper until everything is revealed and almost everyone is dead, illuminated in the light of the smokeless fire of hatred.

I watched the series the first time with the Gutter’s own Alex MacFadyen. And after the climactic scene in third episode, Alex sent me an insight:

“The section of Ave Verum they were playing in Ghoul translates as ‘Be a foretaste to us / During our ordeal of death.’ Ordeal is also translated as ‘trial.’ The rest describes Jesus’ suffering on the cross, with blood and side piercing and it’s usually considered to be about the redemptive power of suffering and how he suffered so everyone else could go on to something better, but in this context it’s such a great choice and a whole other reading.”

Everyone in the interrogation facility is facing an ordeal of death. They have been tried by the ghoul’s summoner, by the ghoul, and even to an extant by each other. The truth of what they have done has found them. Of course, torturers believe that they are finding the truth, when they use pain and a “foretaste of death” to make their subjects affirm the torturers’ stories. The ghoul already knows the truth and tortures its victims with the guilt of what they have done before killing them. And yes there is a parallel here between the interrogators and the ghoul with slightly more sympathy for the ghoul. Humans as the real monsters has a long tradition in horror, and I appreciate it in the context of a story about fascism. None of this is the ghoul’s will. “You’re not like the others,” one of the prisoners says, not realizing he is talking to the ghoul. The ghoul answers, “I don’t even want to be like them.” To it, we are worse than ghouls. Because of course a ghoul does what a ghoul does, but people summon ghouls to take their revenge. The ghoul is not choosing to be among us. It is forced to take our forms, know our secrets, know our guilt, and even consume us.

Taking our forms is not only a way of creating uncertainty about who might be the ghoul and who will die next like in The Thing (1982 / 2011), it’s another way the ghoul torments the condemned. I often think about the slow zombies of yore and that so much of their horror was not only in their cannibalistic desires and their unstoppable pursuit, but in presenting us with people we know transformed into something awful. With the ghoul, the horror is not only being faced with a monstrous version of a friend, comrade, colleague or enemy, but that they *know* what we have done and they are *saying* it out loud. This kind of confrontationally existential horror also made me think of two other movies, Emma Tammi’s The Wind (2018), which I saw around the same time as I watched Ghoul, and, subsequently, Emir Ezwan’s Roh / Soul (2020).* In those films, women are confronted by demons who take familiar forms and reveal terrible things. In Ghoul, Nida is confronted with her guilt and her complicity in a system she believed in. And in the end, after she has been imprisoned in a black site as a terrorist herself, Nida strikes a deal with her blood in her cell, summoning a ghoul to take on the whole terrified and terrorizing state.

*I wrote about them here.

~~~

Carol Borden doesn’t even want to be like them either.

Parts of this piece originally appeared in Carol’s Spookoween 2019: 31 Days of Horror posts at Monstrous Industry.

I love the description of this as “confrontationally existential horror” – having people you know see your worst parts and say the things you are most afraid to hear or face really does add another nightmarish dimension to an already fully horrifying experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! It was not easy to figure out how to describe that element. So I’m glad it worked!

LikeLike