Gaddaar is maybe the best Hindi film of 1973, if not the first half of the 1970s, that you probably haven’t seen. Maybe I’m wrong and you already love it as much as I do, but whenever I bring up this movie, I’m mostly met with blank stares by all but the most seasoned 1970s Hindi film fanatics, and it seems to have fallen into a very undeserved oblivion. If that’s the case for you, it is indeed my great honor to introduce it to you, especially in January in the northern hemisphere, for reasons that will become clear momentarily.

Though the opening centers on a heist by a gang of seven criminals, the bulk of the film focuses on the story of what happens when one of their members runs off with their loot and another shadowy figure offers to help them search if they’ll cut him in on the treasure. In a move unusual for a film industry headquartered in tropical Bombay, hard-core winter enters the action as the traitor is tracked to hotel in the Himalayas, where blocked roads, difficult terrain, and the threat of storm freeze the location of second half of the film, with the isolation and limited movement both adding to and reflecting the increasingly fevered state of everyone’s desperation.

That’s basically the whole film. Despite the vintage and the actors, this really isn’t a masala movie: it lacks romance, family, and religion; there’s no subplot or comic track of any kind; and there are only three songs over the runtime of more than two hours. More to the point, though, none of those absences are felt. Gaddaar is perfect just as it is.

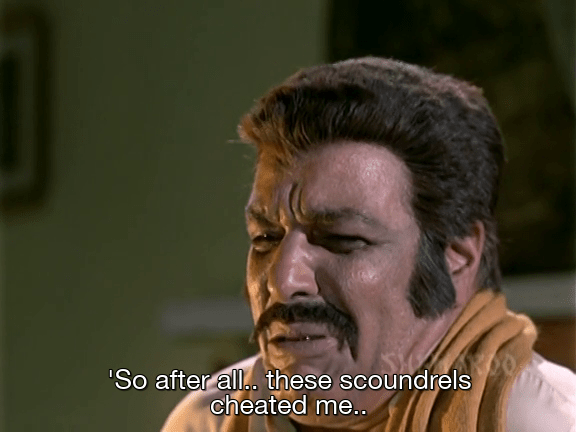

Number one on its list of strengths is the cast. The gang leader, BK, is played by veteran star villain-turned-wise-elder Pran, who spends the first few minutes of the film driving around Bombay in an absolute blue whale of an American car (a nod to the original Ocean’s 11, maybe?) flashing hand signals to his crew, who all respond with an eager thumbs-up. I want nothing more than to have been cool enough in 1973 Bombay to have Pran invite me in on a scheme. Sampat (Anwar Hussain) is a circus gymnast, good at using a grappling hook to climb into a prince’s mansion undetected. The Professor (Iftekhar) has a box of tools to break through a metal grate and the safe. Kanhaiya (Madan Puri) is the wheel man. John (Mohan Sherry) cuts the electricity to the palace and Baboo (Ranjeet) and Mohan (Ram Mohan) are hotheads and eager to punch anyone who gets in their way.

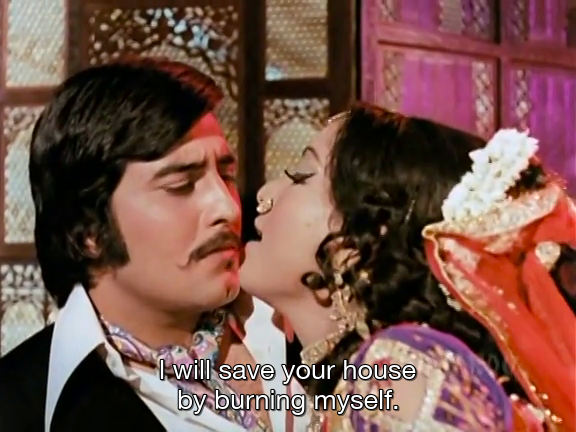

Vinod Khanna—the only person in the cast who was a hero at the time it was made and an unusual intrusion into this gang of character actors—is a lone wolf who forces his way into the group after overhearing what they’re after. He also very helpfully follows up the traitor’s love of cabaret dancers (notably Padma Khanna, who, like many of the men, gets more lines here than usual) and goes to dance clubs all over the country asking the performers if they’ve seen the traitor. They eventually discover the traitor is in a village in Himachal Pradesh, and they spend the remainder of the film in a nearby hotel trying to recoup their money while fighting off the traitor and his staff, as well as surviving the elements and their own fraying nerves.

Chasing is generally more interesting to watch than planning, and director Harmesh Malhotra’s decision to show the effects of treachery after the heist, instead of the lead-up to the heist itself, is a wise one, enabling the writers to explore ideas like loyalty, friendship, identity, professional ethics, ambition, and dreams. These kinds of topics, in turn, give this outstanding cast more material than they get in most other films, and what a joy it is.

I can’t step outside my fervent love of 70s Hindi movies enough to state empirically that all these men are brilliant actors in these roles. I’m just so excited to see them have more than four lines, or be more than a beleaguered cop or slimy rapist, that anything they do would please me. But either way, Gaddaar gives us more time with Iftekhar, who has a scene that genuinely brings tears to my eyes, and Ranjeet, for whom I actually feel a teensy bit sorry, than any other film I’ve seen.

Plus they all appear in an excellent qawwali as the criminals dance around the hotel celebrating their find and taunting the traitor’s betrayal of their friendship now that they have him where they want him. Please watch the first 25 seconds of the song here to see Vinod Khanna be a snake charmer with VAT 69 as his been and Ranjeet as his snake. (The rest of the song is equally great but it contains foreshadowing and the identity of the traitor.)

The actors do not get equal screen time, but the unraveling of Sampat, who for reasons not clear to me dreams of opening his own circus, is almost hypnotizing and not at all what I expected to see.

The value he puts in his talents and ambition is paralleled in BK’s increasingly frantic insistence that he get his hands on this money, not as much for the sake of its financial value as for its symbolism of victory. His character states several times that he does not make a habit of losing, and each time the metal briefcase full of cash slips from his grasp he gets closer to the edge. The violence also escalates, which is a nice counterpoint to the psychological and emotional changes in the characters and makes perfect sense when you lock a bunch of criminals in a room with lots of booze and not much to do except think about their greed and the money that’s just out of reach. The violence also adds to character development, as we find out which person is actually a real creep (which was also a surprise, based on what I’ve seen of these actors’ careers) and which person has a conscience about the innocent bystanders in the hotel who might end up collateral damage. From those differences arise clues to the true identity of a few of the characters and hints at how they will eventually align (or not).

Age is an interesting and, according to the subtitles, anyway, largely unspoken factor in how the criminals are depicted. BK, Professor, Sampat, and Kanhaiya act more as the brains and leaders than the younger men do, and the first two of them in particular are written as long-standing friends who genuinely care for each other, expressed in scenes that make this movie a must-see for anyone who likes Bombay’s gentlemen character actors of this period.

The younger men serve a bit more as heavies, but they have specific personalities too. Age as it affects individuals rather than family or corporate systems is not particularly common in the films I’ve seen, and I did not expect such thoughtful portrayals in a film that I had assumed was primarily interested in stealing and avenging.

The use of color and pattern in this film is really clever. The first segment—that is, the heist and the initial search around the country for the traitor—is near the level of gaudiness one expects from 70s Bombay films. From the very first frame, showing a sunny sky over the seashore in Bombay and then the prince’s cotton candy colored mansion, and across the gang’s wardrobe full of plaid suits with paisley cravats and the costumes and sets of the dancing girls’ songs, this is the lurid world of criminals and cabarets.

But when the action shifts to the mountains, the visuals are mostly more sedate. Blanketed in clean white snow, the land seems silent. People wear big brown or black coats, the walls are panelled in nondescript wood, snow covers most surfaces outside, the mountains and sky are generally gray, and even the scenes outside the hotel take place in utilitarian or rocky spots (a barn, a cave) that are no more colorful. The action is likewise toned down, not in actual scope but in accessories: in Bombay people chase in vehicles and run quickly through paved city streets, whereas in the mountains they stumble over snowy hills on foot.

Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s music, though scant compared to some films of the same era, is used well in Gaddaar. The criminals’ qawwali is my favorite from a storytelling point of view (as well as its surprise factor), because it shows the familial side of a group of people who have committed to and invested in a shared mission—and been through a lot of stress because of it. Padma Khanna has a spectacular cabaret number with Egyptian trappings (and you know how I love Egyptian songs). It’s a fascinating portrayal of female power—maybe a conscious counterpoint to the almost entirely male cast and agents of action in the rest of the film (the only other interesting woman being a doctor and nurse married couple at the hotel who debate the ethics of giving medical treatment to criminals)—featuring Padma as a sort of…pharaoh, perhaps (though minus symbolic beard), whose mere presence sends villagers scattering as she is paraded through the streets in a sedan chair. She selects a male subject (choreographer Oscar wearing yellow leggings and not much else) and brings him back to a sort of pleasure palace, letting him splash in a heart-shaped pool and feeding him grapes and tantalizing drinks from glittering pitchers before sending a poisonous snake after him.

The second song, which features Vinod going from city to city asking various dancing girls if they recognize the photo of the traitor, is also good, and it packs in several different lead dancers and corresponding sets into one song.

I don’t know if Laxmikant-Pyarelal also did the background score, but whoever did seems to have listened to a lot of westerns, because the music that plays while people trek through the snow evokes cowboys to me, complete with strings, trumpets, whistling, and clanging chimes that I picture hanging in the mission church in the ghost town. There’s also at least one really powerful use of silence, a thirty-second stretch that accompanies a dramatic event and I think is supposed to reflect a character’s swirl of emotions and perhaps even his defeat.

Let’s talk about the weather, which is really unusual in Gaddaar. Snow in Hindi films usually plays different roles than it does here: it might be the background for pink-cheeked romantic songs, an exotic playground for high society in furs, or the excuse for a soldier to rescue a heroine who wandered off from her class trip or ski holiday, forcing them to dry their clothes in front of a fire in a cozy cabin. But I’ve never seen another film where the snow and cold are extended threats across multiple scenes. It’s as much a destabilizing force as the traitor is, because nobody except the traitor is an expert at negotiating the cold climate and its impediments, or dealing with the stir crazies that can set in in winter. Snow and cold offer no invigoration and joyful frolicking: they are tense, claustrophobic, and dangerous. The snow creates high-contrast visuals between the glare of the sun and crisp shadows, makes paths slippery, and holds telling footprints.

Fifty-odd years after Gaddaar‘s release, it’s still a compelling depiction of the risks of the criminal life to body, mind, and soul. The script, pacing, visuals, and acting are as tight as Vinod Khanna’s flares. Make yourself a hot toddy and watch it tonight!

Gaddaar is available with subtitles on the Internet Archive and on Youtube without.

~~~

When Beth Watkins flashes hand signs to the Gutter crew, they always respond with an eager thumbs up!

Categories: Screen

1 reply »