The Gutter’s own Carol Borden writes about a recently released film here and includes plot details. I also talk a bit about Sinners later in the piece, but you can see it coming. You’ve been warned.

~~~

There was a store in my town that sold sparkly, iridescent things. It sold stuffy unicorns, dragons and jellyfish. It sold cute stickers, pens with feathers, shiny stationary, and locally made glittery make-up. It was welcoming to all and a lovely place. A corner of the store was devoted to items for building the perfect, tiny fairy house—little doors, chairs, mushroom cap tables and such. All were wee or twee depending on your point of view. There is a demand for such things in these parts. The neighboring city has tiny fairy doors throughout town and you can take a tour to see them. Even my favorite tree has signs of tiny fairies on it. It’s a titanic beech that’s probably two beeches fused together—a tree that seems to demand Shinto shimenawa, Balinese saput poleng, or at least one tremulous H.P. Lovecraft, M. R. James or Dennis Wheatley story about it. Instead of ritual practice or stories about ancient blood rites, this tree had a fairy door and a small toy wishing well placed in its enormous,arterial-looking roots. It is a kind of recognition.

But part of me is irked to see a tree of such majesty recognized as such and responded to with something that is, to me, twee. Something that feels like it minimizes that power and makes it safe just as fairies themselves have been minimized—actually miniaturized—and made safe. At the same time, I recognize a child might have made that fairy house among the roots. And I don’t need fairies to frighten children or people’s gardens to be awe-inspiring or terrifying. There have been, after all, many kinds of fairies, fairy trees and fairy doors.

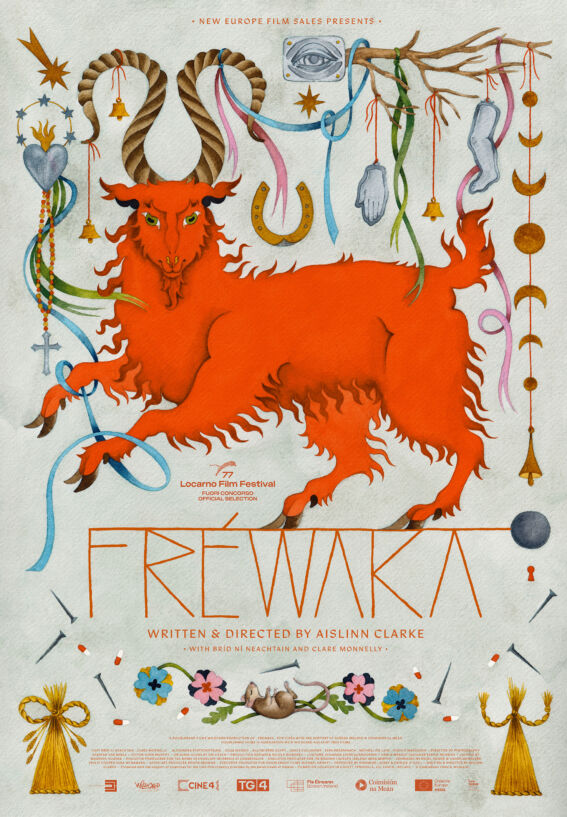

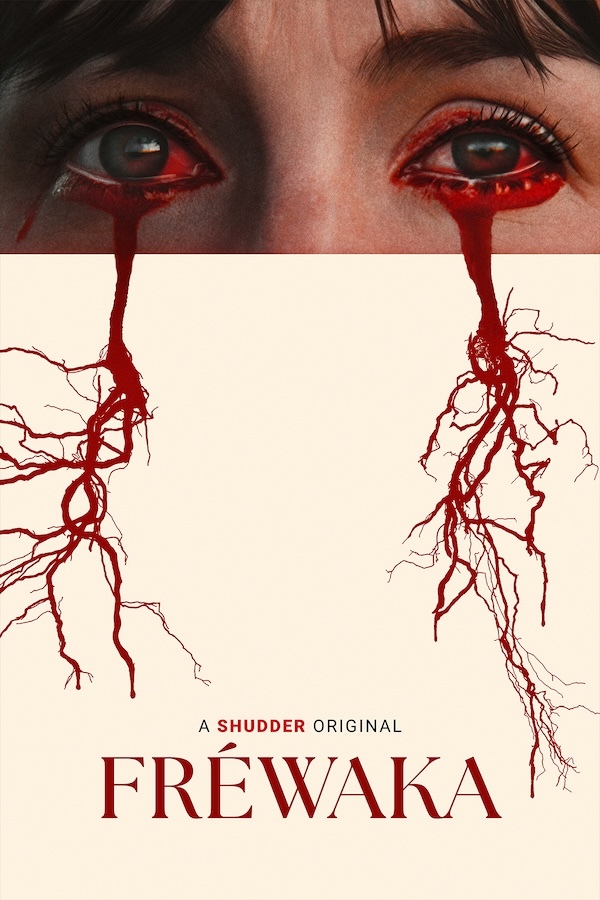

There is nothing charming about the red fairy door we encounter in Aislinn Clark’s Irish language horror film, Fréwaka (Ireland, 2024).* Its fairy tree is old and hung with scissors and bones. And there is nothing safe about the Good Folk attracted to the house with the fairy door in it. Fréwaka opens with a wedding in 1973, the same year The Wicker Man (UK) was released in Britain. That feels pointed and significant, though Fréwaka is very much its own film. Peig (Grace Collender) is pregnant and near to giving birth when she marries Daíthí (Mícheál Óg Lane). The period detail is wonderful, but unfortunately the wedding is not. Peig seems detached from it all. Men in 1960s-style black suits with skinny ties and wearing masks made from dried corn leaves appear at the reception. They bring with them a goat wearing a garland of roses. A goat with a garland is always a good sign for me in a film, but often a bad sign for the protagonist. Peig tells Daíthí that the men weren’t invited. Daíthí laughs and tells her that’s the point—they come when they are not invited. During the celebration, Peig wanders away from the revelry and light. She disappears. All that is left behind is her gold claddagh wedding ring.

In the present, Síubhán (Clare Monelly), called “Shoo,” and her pregnant fiancee, Mila (Aleksandra Bystrzhitskaya), are clearing out the apartment of Shoo’s recently deceased mother (Tara Breathnach). Shoo’s mother had hanged herself while singing a song that recurs throughout the film, “Éamonn an Chnoic”, aka, “Ned of the Hill.” She was a difficult and abusive woman, forcing Shoo to memorize the “Salve Regina,” a plea to the Virgin Mary. Any time Shoo made a mistake reciting the prayer, her mother would burn her. The line “pray for us poor banished daughters of Eve” is another refrain throughout the film—a very pointed one.

Shoo is relieved of the responsibility of dealing with her mother’s apartment, her own feelings and any conversation with Mila about either when her agency texts her. Shoo has received a two week home care placement to help a woman recovering from a stroke. But if her upside down horseshoe pendant is anything to go by, Shoo’s luck is not likely to hold. She leaves Mila with her mother’s apartment in Dublin, and heads for rural Ireland, to Peig’s home. Peig (Bríd Ní Neachtain) is alive. She is widowed and living on her own outside of town. The townsfolk have no respect for her, though. On the bus, a haunted-looking old man suggests Shoo not go to Peig’s house, but eventually gives her directions to a stone country house “to the right of the fairy tree.” I suspect the disrespect is a combination of thinking Peig’s a crazy old lady and a fear that associating with Peig might catch “their” interest and attention. The townsfolk don’t say anything about that, not directly, but there is that well-tended fairy tree near Peig’s home, with its wards and charms dangling from ribbons, and candles in the roots and hollows circling its base. The local folk might not exactly believe, but they are avoiding taking chances. And while I do mention two men, men have a very minimal role in the film, aside from the sinister besuited and masked men who appeared at the wedding. Fréwaka is a film about the abducted, banished, and abandoned daughters of Eve.

Shoo is supposed to care for Peig while she recovers, but Peig isn’t so sure of Shoo. She isn’t sure Shoo is a caretaker. She isn’t sure if Shoo is human or one of “them.” She allows Shoo to stay after testing her. Peig makes Shoo oatmeal with extra salt. She makes Peig tap a horseshoe three times before entering the home. “There are certain things they don’t like: pure metal, salt, and piss,” Peig tells Shoo, testing her with all three. For her part, Shoo is visibly annoyed, but also complies with the requests. After all it is Peig’s home and Shoo has dealt with worse for far longer than a few weeks.

As Peig grows to trust Shoo, she talks about her abduction on her wedding night. Peig tells Shoo that her husband made a deal, a bad deal, with “them” to get her back. Regretting his deal, hounded by them, Daíthí killed himself. And by “them,” Peig means the Good Folk, the Sidhe.** And the Sidhe have been trying to get her back, ever since. Peig knows they are there, behind a red door that leads to “the house below the house.” And they are, as Peig tells Shoo, “sniffing around you,” too. Shoo starts to have dreams and hallucinations of her own. And she’s become interested in the red door Peig keeps shut and surrounded by wards and charms that she counts and checks repeatedly. It could be the actions of a woman with dementia maintaining some sense of control as she declines. Or it could be the actions of someone who the Sidhe want back maintaining some sense of safety as she tries not to fall apart. Shoo herself passes through the ominous red door and in Peig’s basement she finds a wedding album, with newspaper clippings confirming Peig’s disappearance. I appreciate when a story uses a medium as a medium in both sense of the word. In Fréwaka, the Sidhe use phones and computers, and even newspapers to taunt, terrify and trick the objects of their fascination.

The only friendly contact Shoo has in town is with a woman named Méabh (Dorothy Duffy). It might be nothing, but Méabh appears very 1980s in her styling in the same way that the woman who runs the town shop—and is nasty to Shoo—appears very 1960s matron in her styling. It’s easy to start seeing things in the village as Peig does. Are these human women caught in styles they liked at a particular time? Is it the slowness of fashion to reach rural areas? Or are they not what they seem either? After all, there are still the men in 1960s style suits, probably not so long ago to the Sidhe. Regardless, Méabh has an evocative name— one that evokes Shakespeare’s Queen Mab, the warrior queen of Connacht in the Táin Bó Cúailnge, and the goddess Méabh Lethderg, or possibly all of them at once. Méabh tells Shoo that Peig had been in an asylum or maybe a Magdalene laundry. Magdalene laundries were state institutions run by convents where “fallen” women and girls were sent to do laundry, sewing, cooking, cleaning and other domestic work. It was unpaid and involuntary incarcerated “penance” of indeterminate terms for being a fallen woman of some kind. Women and girls could be sent to the laundries by the police, the courts or their families. The laundries existed throughout the English-speaking world, particularly in the British Commonwealth, but also in the United States for a time. But they persisted the longest and the most notoriously in Ireland. There, sex workers, unwed mothers, difficult, inappropriate, disabled, queer, and sexually abused women and girls would work off the sin of being who they were or what happened to them. These laundries still operated in the 1970s and continued until a scandal in 1993 revealed a mass grave of 155 women “employed” by a Magdalene laundry. The last laundry closed in 1996.

Peig was likely one of those women, casting a particularly painful light on her description of her time in the “house beneath the house.” The landscape of a more cruelly punitive world hidden behind the image of an ideal one. As Peig points out to Shoo, the Sidhe are also interested in “women’s work,” the work of marriage, birth and death.

“What’s it like down there?” Shoo asks. Peig’s answer contains so much incredibly painful horrific history.

“A mad house. A famine village. A laundry house. A coffin ship. A field, poisoned with blight. A street full of blood and bullets. Hundreds of bodies piled into a septic tank. Punishment.”

Like the Good Folk in Fréwaka, Magdalene laundries snatched women and children, punished them, returning them—if they did return them—scarred and changed.

The Good Folk of Fréwaka make clear that there reason they are called “The Good Folk” in a similarly euphemistic way that the Furies are called, The Kindly Ones. In “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” the fairy court are fickle and bored beings interested in human art, beauty, and, worringly, children. And before that, the Sidhe were associated with the mythic Tuatha Dé Danann, ceding the Earth to humans and living in another world, perhaps the Summerlands, accessible through places and times where the veil between the worlds is thin—places like tumuli, barrows, mounds and places in the earth. In Fréwaka, their world might be accessible through a basement, that fraught netherplace central to so much horror.

Sometimes fairies are merely attracted to our music and joy, so they can dance and sing with us. And liminal times like births, weddings and wakes can thin that boundary between our world and theirs. Sometimes they covet human music and joy. And sometimes, remembering perhaps that the Earth was once theirs, that they were once gods and not little sparkly stickers or utterly disneyfied, they resent and hate us. In Fréwaka, the Sidhe hate us and their Otherworld is not a place of endless summer, dancing and often exhausting gaiety.

I saw Fréwaka after seeing Ryan Coogler’s Sinners (2025). I saw them on the same day, in fact. And there was some unexpected resonance between the films for me. There is, of course, the Irish man and the Irish music. There is the continuing pain, injustice and violence of history. There are also some parallels in the presence of the Sidhe and the vampires, and of the spirits delighting in human music, art and joy. It’s good right now to be reminded of human beauty and joy, not to fall into a seemingly enlightened but ultimately destructive misanthropy that denies these things and falls in line with the beliefs about humankind held by the shitheels intent on destroying it.

In Sinners, spirits from all over are attracted to Sammie’s (Miles Caton) music in Smoke and Stack’s (Michael B. Jordan and Michael B. Jordan) juke joint. Even the vampires who are not exactly spirits, but behave much like the other beings who appear (Sun Wukong!), are drawn to it. Unable to enter, the vampires remain outside singing and playing Irish folk music. But there’s also the anti-colonial Irish vampire Remmick (Jack O’Connell). The fact of his love of music would be enough of a confluence for me, but then here is his vision of a new world of inclusion and acceptance through music and love, which sounds good but is really him controlling and colonizing everything despite what I think he thinks are his sincere beliefs. Like the Sidhe, the vampires of Sinners steal human beings and replace them with some other thing. In Fréwaka, the Sidhe like our music and our celebrations, but as far as we know, aren’t interested in “inclusion.” They do have an idea of what the order of the world should be, though. They follow different rules, but the Sidhe, like vampires, stand outside the celebration until Peig leaves its relative safety and finds them. Like the vampires, the Sidhe must be invited into Peig’s house. And the Sidhe, at least, can be disinvited, if you have salt, pure metal, or enough urine. I suppose it’s the same with vampires if you have enough garlic.

I felt such a moment of profound resonance between the films when a woman waits for Shoo to invite her in and the camera notes that she wears shoes with no socks. And then again when Peig uninvites the woman. Both share a sense that the people you know might not be the people you know. I don’t know if anyone else would have the same experience seeing the movies together, but for me it was art breaking down the barriers in the world, like Sammie’s music in that scene in Sinners.

The resonances with Sinners surprised me, but in writing about Fréwaka briefly last month, I wondered if it would pair well with movies like I Am The Pretty Thing That Lives In The House (USA, 2016); She Will (UK, 2022); and, You Are Not My Mother (Ireland, 2021), another Irish horror movie directed by a woman that concerns a difficult mother/daughter relationship, mental illness, how social taints are passed down from generation to generation, and the Sidhe. And there’s Paul Duane’s All You Need Is Death (Ireland, 2022), which concerns a folk song that could be a curse or could be a cage for something that seems like it might be Sidhe. All these films would pair well with Fréwaka.

I warned about spoilers at the beginning of this piece, but I don’t really think it is a spoiler to talk about the Sidhe as real in Fréwaka. I like stories where there is more to the world than we know. And there are things not so easily explained by, “Well, the old lady’s crazy.” There are plenty of those stories about women losing their grip on reality and plenty of good ones, especially in 1970s horror. But I like a story that’s about, “What if the crazy old lady were right?” One of the central horrors of our time is that the horrors are real, not imaginary and the horrors are being treated like they are imagined. In Fréwaka, the Sidhe are in the village at weddings and wakes. They are kidnapping and killing people. The Sidhe are real, they hate us, and the people of the village don’t talk about it, probably cannot talk about it safely. They decorate and tend the fairy tree, hoping all the cruel things don’t happen to them and shun the poor, banished daughters of Eve.

*As the Gutter’s own Sachin Hingoo notes, both Fréwaka and John Farrelly’s An Taibhse / The Ghost (Ireland, 2024) claim to be the first Irish-language horror movie. They are very different movies, though.

**I know there are newer terms, but Peig uses “Na Sidhe.”

Full disclosure: I received a review copy of Fréwaka. The film is available on Shudder or AMC+.

~~~

Carol Borden would not open any of the many red doors in horror movies of the last 20 years.

8 replies »