The winds of November are blowing, my friends, chilling our souls in the Musuracan shadows and grayscale skies. Making us hanker for some noir, but grieving over our options on long autumnal nights. Maybe you’ve seen Double Indemnity (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Out of the Past (1947), Mystery Street (1950), Body Heat (1981), Blood Simple (1984), Heat (1995), Drive (2011), or even Bound (1996) too many times, as hard as it is to believe, but you’ve still got the itch for some classic noir, neo-noir or even neon noir. Maybe you’re feeling some ennui and are looking for something different. Maybe you’d enjoy some Chinese neo-noir. There are a lot of good films I’d recommend: The first Chinese noir I saw was probably Lou Ye’s intricate, genre-blending (gangsters! mermaid!), Suzhou River (2000). Suzhou River is more a film that uses generic conventions than a straight crime drama. Fellow Sixth Generation Filmmaker Jia Zhangke’s Ash Is Purest White (2018) leans towards a character portrait and drama about a woman who defends her gangster boyfriend during a shootout and is abandoned by him with neo-noir framing. Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018) is a stylish, neo-noir about a man haunted by the memory of a woman that veers into magical realism. And it has a stunning 59 minute single take second half that was projected theatrically in 3D. Wen Shipei’s Are You Lonesome Tonight (2021) is a solid crime film with nice cinematography, intriguing lighting in night scenes, and a classic Hays Code era crime does not pay ending. An HVAC tech (Eddie Peng looking straight out of The Machinist) flees the scene of an accident. There’s a bag full of money. And there’s a widow played by the legendary Sylvia Chang. All of these films are solid options. But I’m going to talk about two films that made me search out more. Diao Yinan’s Black Coal, Thin Ice (China, 2014) and the follow-up, The Wild Goose Lake (China, 2018).

Things have changed in Chinese crime cinema since I wrote about Hong Kong filmmaker Johnnie To’s 21st Century crime films that occasionally, to the consternation of Chinese officials, compared the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party to gangs. Since then, China has continued to produce nationalistic battlefield epics and blockbusters that please government officials and mostly turn me off. Most nationalistic epics and blockbusters turn me off these days. But Chinese filmmakers have also been producing some excellent neo-noir, often with elements of Classic Hollywood film noir caused in part by some of the same kinds of censorship pressures. And instead of setting them in the distant past before the Chinese Communist Party made a just, harmonious and crimeless society, the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration (formerly SAPPRFT and SARFT) is allowing some crime films to be set not only in the recent past, but the present day as long as the good guys win and the bad guys are punished. Unless you are Johnnie To or another Hong Kong filmmaker or actor who supports democracy, in that case your films are in danger of being labeled national security threats and disappeared.

Maybe it’s easier to make contemporary crime films and navigate government censorship when you are not from Hong Kong but Xi’an. In contrast to To writer/director Diao Yinan has had international and domestic success with noir that depicts sex, prostitution, rape, serial killings, crime and even violent, drunken, barely competent detectives. Things the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration has historically disapproved of representing in Chinese art. Where To has been using crime film to criticizes the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party, Diao has found a way to work with and within the system to make the genre films he wants to make. Sometimes the results look like neo-noir—or even neon noir—but they also feel very much like the classic Hollywood film noir made under the Hays Code.

People who might not enjoy the conscious artfulness of Suzhou River but do enjoy classic Hollywood noir and neo-noir style might well enjoy Diao’s first noir, Black Coal, Thin Ice. Set in China’s northernmost province, Heilongjiang, the film feels like it might as well be set in winter itself. The winter light and monochromatic colors make the film appear at times as if it were shot in black and white. Other times, the film is almost neon noir, literally using neon signs for lighting in gorgeously composed scenes shot by cinematographer Dong Jinsong. In one scene we travel from 1999 to 2004 in the space of a highway tunnel that is gloriously, sulfurously yellow and then monochromatically black and white as we emerge into a winter storm to see a drunk man slumped against the concrete wall of a highway ramp with his motorcycle parked in the road. The film has a wonderful sense of style and in an interview with Film Comment, Diao says, “The cynicism on the surface may hide the deep despair. Cynicism is a form of expression. It is the expression of a personal style when one is deeply disappointed with society, the politics. The style becomes the best weapon against mediocrity and decay.”

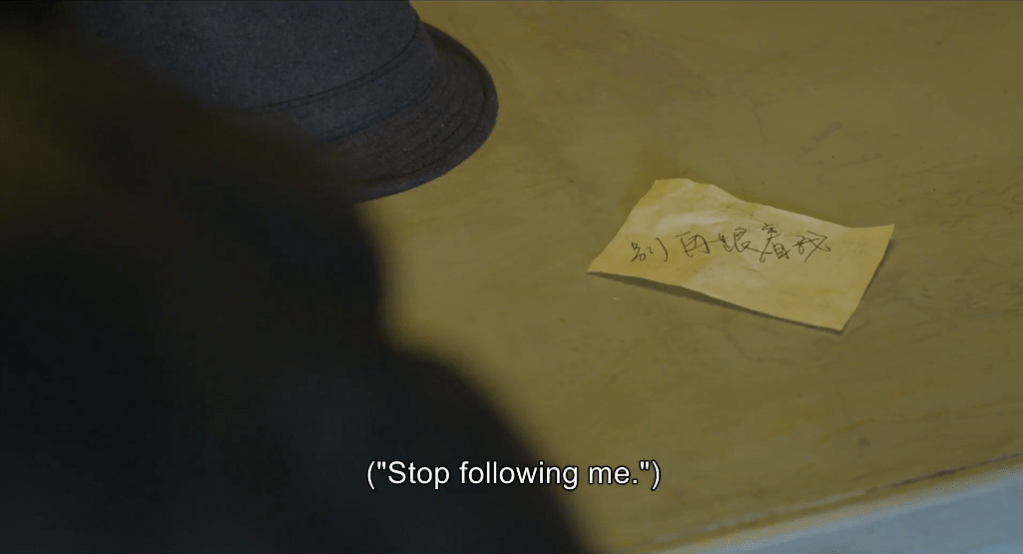

There is style to burn in both Black Coal, Thin Ice and The Wild Goose Lake. And cynicism definitely hides a deep despair in the heart of Zhang (Liao Fan**), the drunk man on the side of the road. In 1999, Zhang was a police detective involved in the investigation of a murder. An arm was discovered carried along in a coal plant’s conveyor system. The murder victim is identified as Liang Zhujin (Wang Xuebing) from his bloody uniform and ID on a lanyard. But his body parts are being discovered in coal plants all over the province. Det. Zhang and his partner Wang (Yu Ailei) accompany two more detectives to arrest two suspects at a hair salon. It turns into a mess with the suspects dead, two of the detectives dead, and Zhang shot. Five years later, Zhang is working security, but drinks like that’s his job. One night, Zhang sees his ex-partner Wang on a stakeout of Liang’s wife, Wu (the transcendent Taiwanese actor Gwei Lun-Mei). Wu has been tied to two more deaths. Zhang starts showing up at the dry cleaning shop Wu works at. He follows her home. He’s obsessed with redeeming his life by solving Liang’s murder, but also with Liang’s widow. Zhang wants to make some kind of connection, but he’s terrible at it and no good at eliciting enthusiastic consent. He is brutish and lumbering and the bulky leather bomber jacket and leather snow pants Zhang wears only makes him appear even more brutish and lumbering.

The best date he’s had in the five years since his ex-wife had goodbye sex with him in a bedbug-infested hotel room–before handing him his copy of their divorce certificate–is sitting in the backseat of a car with a haunted, dissociated Wu. She is surrounded by death. She says every man who has loved her has died. And the men who do love her, are violent and groping. Like many a woman in classic film noir, Wu is both a victim and, maybe, a femme fatale just one working in a dry cleaning shop, which I love. Gwei Lun-Mei does incredible work with her facial expressions and posture alone.

Black Coal, Thin Ice seems influenced by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories Of Murder (South Korea, 2003), in which local provincial police try to solve a series of serial killings with their usual, violent methods, but the police are out of their depth and lack sufficient support to do the kind of investigation that would catch their killer. Like Song Kang-ho’s Det. Park Doo-man*** in Memories of Murder, Black Coal, Thin Ice’s Zhang is out of his depth, a cop on the margins struggling to catch an apparent serial killer. Unlike Det. Park, though, Zhang is also pursuing something like intimacy, something he might believe is love. Love might exist in the world of Black Coal, Thin Ice somewhere, but love and intimate connection also appears not so much as an illusion, but as a delusion of men who are groping for it—literally—and women who are trying to break free—literally—however they can. But despite the bleakness, both films do have a sense of humor. There is a horse not in a hospital, but in an apartment building in Black Coal, Thin Ice.

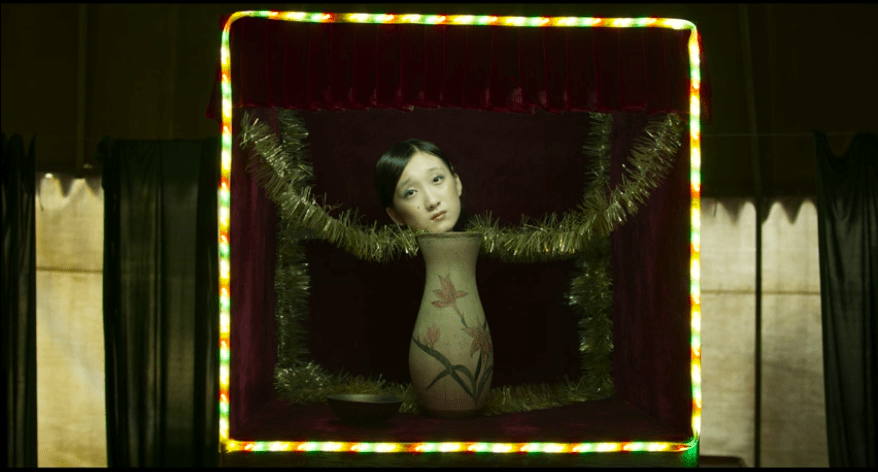

Gwei Lun-Mei and Liao Fan, without his signature mustache, return in Diao’s follow up, the more neon noir, The Wild Goose Lake, aka, The Rendezvous at a Rail Station in the South (2019). Gwei plays Liu Aiai, a “bathing beauty” sex worker at Wuhan’s Wild Goose Lake sent by her boss Huahua (Qi Dao) to meet motorcycle thief Zhou Zenong (Hu Ge). Zhou went to jail for shooting a cop and everyone’s been waiting for his release, gangsters and cops alike. Zhou wants to meet with his wife Shujun (Wan Qian) and go on the lam, but the police, led by Captain Liu (Liao), have been watching her. Liu is willing to do anything, including extortion, to get Zhou. The police have also offered a generous reward Zhou, dead or alive. And everyone wants that money, including Zhou, who puts into motion a plan for Shujin to collect.

It’s a fairly straightforward crime plot, if occasionally hard to follow, but it doesn’t matter because it is executed with such flair. Dong Jinsong returns as cinematographer and the film’s lighting designer is Wong Chi-Ming. Wong, a longtime lighting designer for Wong Kar-Wai and it shows. The film plays to Diao’s strength with composition, blocking and especially the choreography of characters in motion. In Black Coal, Thin Ice, we have the ice skating scenes and an intriguing moment where Zhang dances joyously against the fluid background of much more disciplined dancers in a ballroom dance studio.

I love the instructor in the background who gives off such a realistic sense of just waiting for a disruptive, probably drunk man to get tired and leave.

With The Wild Goose Lake, Cinematographer Dong Jinsong returns to give us a fantastic sequence where Liu Aiai follows Shujun to a night market where people are line-dancing in light up sneakers. The camera almost runs a relay with Liu Aiai, Shujun and Huahua as everyone dances to Boney M’s “Rasputin.”

Shortly after, there is a scene almost lit by the sneakers as gang members beat a man. And there is a wonderful sequence set in a zoo at night, as liminal a place as can be. It includes one of my favorite cinematic trends of the 2010s: Tiger outta nowhere.

As with many a noir, classic, neo and neon, The Wild Goose Lake features powerful men abusing their power violently and women enduring, but also secretly serving their own unspoken interests. There is a rape in the film that is not graphic, but it is “realistic.” A man recognizes Liu Aiai as a sex worker and assumes she has no right to say no. It’s upsetting, as rape scenes are, but the depiction does not layer on new upsetting elements. It’s not sexy. It’s not an excuse to see Gwei Lun-Mei naked. And the man does not seem powerful before, during or after the rape. At most it seems like an attempted underscoring of something that is already clear in the film and therefore unnecessary: Men take what they want if they can and women suffer and bide their time. I mention this as a content warning, but also because it is stunning to me that this rape could be depicted in a Mainland Chinese film, that it could make it past censors, and that it could be screened in China. And I wonder if this scene is present in the film just because Diao could do it. Meanwhile Johnnie To has to be careful in portraying Triad hand signs.

I think To would agree with a saying Diao uses in an interview with Filmmaker: “Criminals and police officers are one family.” But they mean it and understand it differently. In To’s films, this brotherhood underscores the potential corruption of the police and how, in his words, they might be just another gang, as the Triads are, as the CCP is in Election (2005), Election 2 (2006), and Exiled (2006). But Diao views it slightly differently.

I’m sure you probably have a similar expression in the US, but in China we say criminals and police officers are one family. Often in order to arrest a bad criminal, you need to be even worse on some level, out-criminalize them to catch them. Because you probably couldn’t bring them in if you’re being polite or civilized. It’s a necessary evil.

For Diao in his films, apparently, the brutality of the cops, their scheming and manipulation, serves a just end. And it’s possible that this is how his films get made with little interference from censors. In Black Coal, Thin Ice and The Wild Goose Lake, cops do what they must, no matter how distasteful, to ensure that crime doesn’t pay. And while the films are entertaining, it’s disturbing that it might get a pass from censors because they agree with former detective Zhang and Captain Liu that the state must pursue its justice by any means necessary.

*I first stumbled across Black Coal, Thin Ice on my library’s streaming service. I’d never heard of it and it wasn’t streaming anywhere else or available on an English language dvd or blu. So please take advantage of your public library system’s resources. And please support public libraries in concrete ways if you want to support film preservation and access to films. Making sure you have your own physical copies of films you like is smart, but it is not enough by itself.

**Liao Fan and Diao Yinan also appear in Jia Zhangke’s Ash Is Purest White. Liao also plays a doofus in that.

***Song Kang-ho is one of the greatest actors of our generation.

~~~

Carol Borden is just dancing to Boney M in light up sneakers. No reason to suspect a heist is planned. No reason to suspect a briefcase full of cash is involved. No reason at all.

Categories: Screen

2 replies »