This week’s Guest Star is Michelle Kisner. Keep up with her on Instagram at @robotcookie!

~~~~

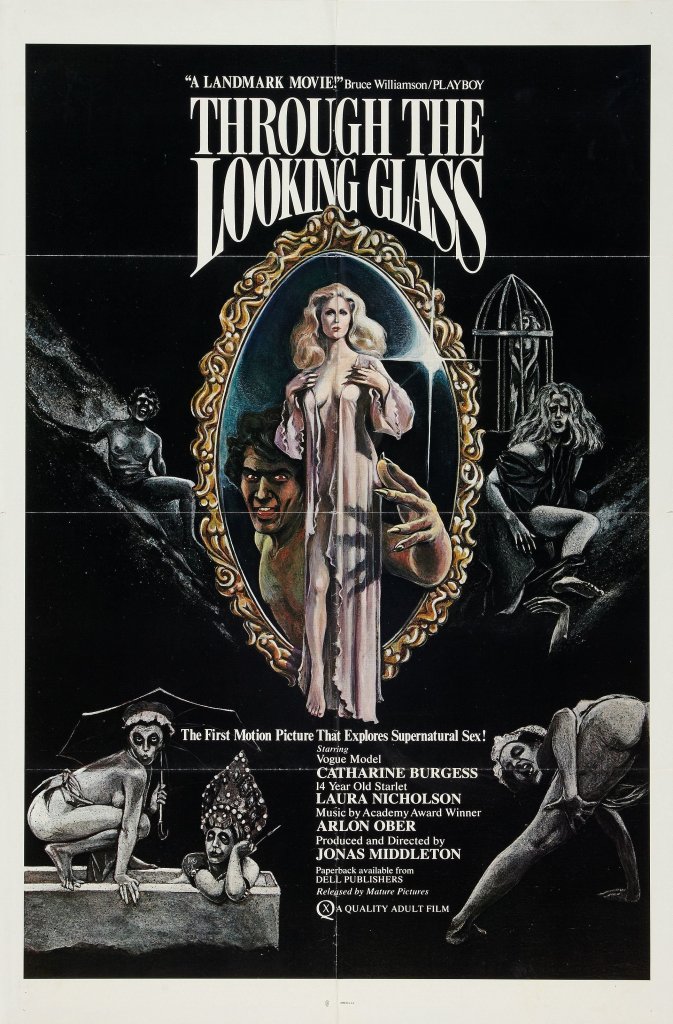

Pornography generally has a negative reputation, and it’s fair to say that most modern porn is primarily focused on sexual gratification. However, there are exceptions, as some classic films have successfully integrated deeper artistic intentions with hardcore, unsimulated sex. Notable examples include In the Realm of the Senses (1976), Cafe Flesh (1982), Shortbus (2006), and Behind the Green Door (1972). These films use real sex as a form of artistic expression and, in some cases, function as a critique of traditional porn, challenging the idea of using sex solely for sensuality or arousal. Through the Looking Glass (1976) explores multiple themes, engaging with the excitement of voyeurism while also addressing the unsettling feelings associated with abuse and tragedy.

The film begins with a woman’s face covered in a creamy white makeup mask as her expressionless eyes gaze straight ahead. This is the viewer’s introduction to Catherine (Catherine Burgess), a wealthy woman receiving an expensive spa treatment. Despite being fawned over by the worker, she remains emotionless, sitting perfectly still, much like a doll or a mannequin. “We’re gonna make you special!” the hairdresser croons as he fusses with her hair as the other women in the spa remark on how cold and aloof Catherine seems, further cementing her wealthy detachment.

Catherine lives in her childhood home, a giant mansion owned by her father, played by Jamie Gillis. Her memories of him are intercut with the present day throughout the first act, in a stylized, dreamlike state where she runs through a misty forest searching for him. As the narrative explores her home life, it becomes evident that she is also distant from her family, rarely interacting with her husband and young daughter. It almost seems like she is drugged or perhaps trapped in her mind. Later that evening, Catherine spurns sexual advances from her husband, recoiling at his touch.

The only place that Catherine feels alive is in the expansive attic of the mansion, which is filled with articles from her childhood and a large baroque-style mirror. Symbolically, the mansion represents her physical body, and the attic is her mind, filled with dusty memories and sequestered from the rest of the house. This is the only place where she is allowed to express her true feelings.

An evocative scene has Catherine masturbating in front of the mirror while looking at her reflection, repeating the phrases her father said to her while he was molesting her. It is as if she is possessed, and eventually, her father’s voice is superimposed over hers as she talks to herself. Her view of herself is filtered through the trauma of the memories of her father’s transgressions, and it is mixed with her sexual desires. Perhaps drawn to her pain, an incubus in the form of her father emerges from the mirror and begins to stimulate her manually. In one of the most infamous scenes, the camera switches to a first-person view and enters her vagina endoscopically (which was a brand new medical procedure at the time). This symbolizes the narrative literally entering Catherine’s inner thoughts and psyche, marking a turning point as the film enters its surreal phase.

Internalization of trauma is a central theme lurking underneath the sexual scenes, and though there is hardcore sex peppered throughout the runtime, it almost always serves the narrative. Catherine has never recovered from her abuse and feels “filthy,” which is further reinforced by an extended scene watching her douche before an evening where she anticipates having sex with her husband. On the surface, this was very likely included for a sexual fetish, but it also plays into the idea of abuse victims blaming themselves for the horrors that they suffered through.

In the second act, the film acknowledges its references to Alice in Wonderland by having Catherine travel into the world of the mirror, where she is at the mercy of the inhabitants’ sexual desires. The biggest set-piece in this section is a take on the Mad Hatter, with a group of reprobates enjoying a “tea party” that includes a woman who looks exactly like Catherine as the main course. Not only are various pieces of food inserted into her orifices, but they verbally debase her as well, commenting on her looks and sexual abilities. Society sees women, and by extension, Catherine, as nothing but an object to be consumed and then tossed aside.

As the narrative embraces the fantastical, it gradually shifts into horror after Catherine enters the mirror world for the last time. The beautiful forest is gone, replaced with a red-tinted desert hellscape filled with babbling sociopaths who are also consumed by their suffering. A highly flexible man constantly masturbates and ejaculates on his face, two women bathe in a tub filled with urine, and various other miscrates engage in frenzied sex with no stopping. It is as if Hieronymus Bosch’s Hell painting has come to life. The incubus cackles by the mirror, taunting Catherine with a slim hope that she can escape, but she is trapped there forever, transformed by the abuses of her childhood. Through the mirror, she can see her young daughter preening herself, likely heading for the same fate, and she is powerless to stop her—quite the nihilistic ending.

Through the Looking Glass operates in a strange space where the hardcore sex will be too much for some arthouse viewers to handle, but the surreal asides and lengthy character examination will be too dull for those just looking to get off. However, it expertly uses sex as a narrative device to tell a haunting tale, and it dives deep down into the type of horrors that many films only allude to.

~~~~

Keep up with Michelle Kisner, her writing and her podcast appearances on Instagram at @robotcookie!

Categories: Notes

Wow, never heard of this despite my obsession with all things Alice. Fascinating.

LikeLike