Spoilers for a key event in the first half of the film; if you’re experienced with Bollywood, it’s nothing you wouldn’t predict.

~~~

I can’t explain why I decided to revisit this time-travel flop from 2008.

Maybe 2025 is making me empathize with flops. Maybe I hoped I could find a few gems in a film that nobody talks about anymore. Maybe 2025 is feeling so dystopian that I might as well think about a jump into the future instead.

And you know what? I don’t regret it.

Not much, anyway.

When I first watched Love Story 2050, I dismissed it as dull despite its trappings of doomed love and very mildly speculative fiction. Doomed love is something Hindi cinema handles regularly and beautifully. Bending the space-time continuum to teleport magically from Mumbai to Switzerland for a romantic song sequence is also old hat, but literal time travel was new to me in this context. If the Wikipedia list of Indian time travel films is anything to go by, this is only the third one (and the first in Hindi), and it’s the first to stay in the relatively near future—a future that should be reachable by a sizable proportion of the people who watched it when it released.* For me, that’s a good enough reason to poke at it with a more generous spirit than I did before.

The first half of Love Story 2050 takes waaaaaay too long to establish the present-day love of Sana (Priyanka Chopra) and Karan (Harman Baweja, son of director/writer Harry Baweja and producer Pammi Baweja). Karan is a discontented rich boy who has nothing to do other than wear down Sana’s resistance to his…well, he doesn’t have any charms, unfortunately, but he’s determined. Baweja is, I think, supposed to remind audiences of the massively popular Hrithik Roshan, but as a friend said, he’s Kirkland Hrithik. (Apologies to readers who don’t shop at Costco; that implies a nearly-generic kinda-flat substitute.)

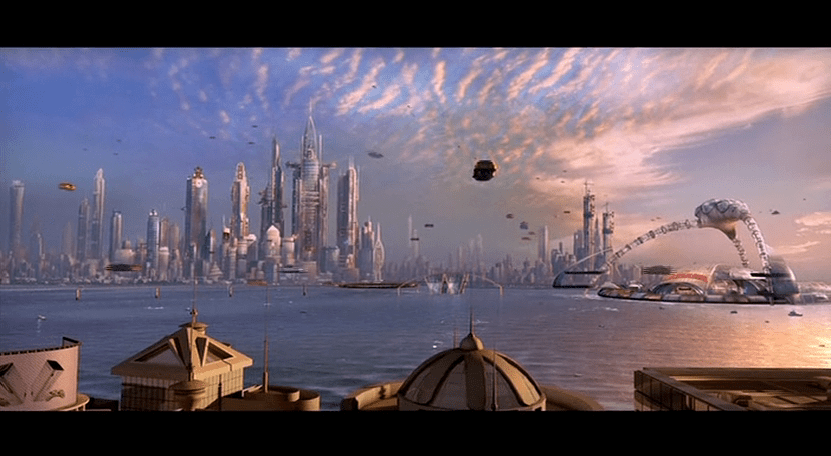

When the pair is suddenly separated by Sana’s untimely death, Karan leans on his genius inventor uncle Dr. Ya Khanna (gentlemanly comic stalwart Boman Irani) to use his time machine—which exists in his whimsical South Australian house with little fanfare, other than Karan explaining to Sana that Ya quit a job at NASA to devote himself to time-travel research—to take him into the future to look for Sana there, convinced that their connection will help them find each other again. The rest of the film takes place in Mumbai in 2050, a sparkling city of clear sunny skies and flying cars and an international pop phenomenon named Ziesha (also Chopra…wait, is this where she got the idea to try to be a global star?), whom Karan must re-woo. But there’s a catch: Ya’s machine is set to return to 2008 in 30 days, and if he and Karan and Sana’s two little siblings who stowed away on the ride miss that window, they’re stuck in the future forever.

All well and good. Like doomed love, reincarnation is also a standard-issue Indian cinema plot point, and many films handle it with enthusiasm and creativity. Supported by ancient and vast cultural context in a Hindu-majority country, it’s a great way to reunite couples or families or to take revenge. As creative license, it’s limitless: go as far back or forward as you want! Cast the same star in both versions of a soul or mix it up! Make them visually identical or wildly different! Let them have full knowledge of their past [which I don’t think I’ve ever seen] or discover it in fits and starts dramatically indicated by fainting or headaches! Adding time travel to the mix gives another layer of creative potential. All of this could be great fun.

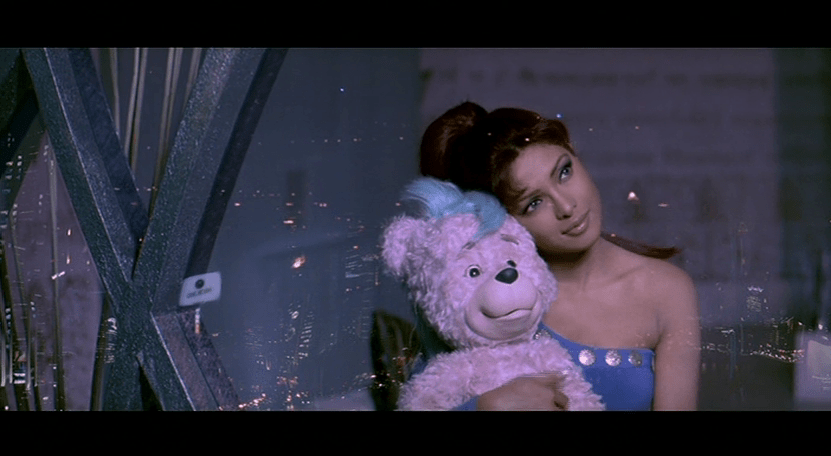

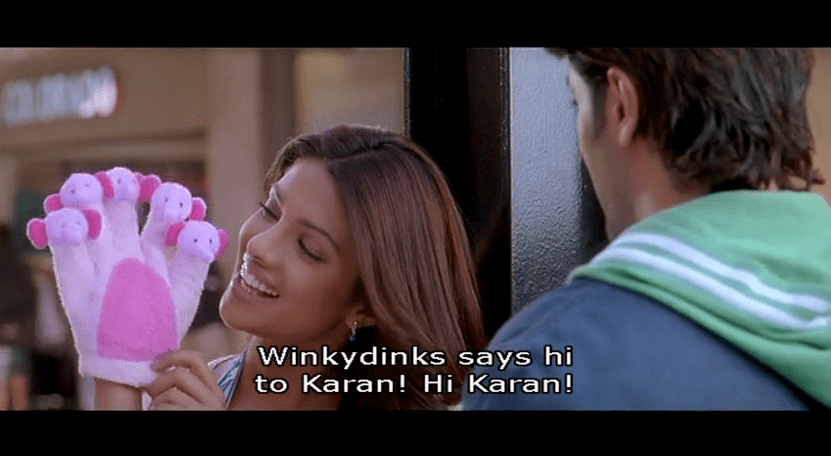

The issue with this film, I think, is its characters. In the first half, Karan is both aggressive and blank. Sana is juvenile, teetering on manic pixie dream girl in that popular media way that makes you think she was written by a pedophile. In the second half, Karan’s unusual mission and his attempts to figure out how to be effective in an unfamiliar world give him a little more substance, but Ziesha is an egotistical jerk whose only friend is a robotic teddy bear named Boo. The contrast in Chopra’s characters is, I assume, supposed to be a compelling irony: Sana is sunny but Ziesha is icy and temperamental like Miss Piggy, Sana journals in a colorful notebook but Ziesha writes music in a lonely lair. Admittedly, when the film eventually shows the thread between the two, this adds dimension to Ziesha’s tolerance of Karan’s curious presence. But both halves are perfunctory.

If director/writer Baweja wanted to hinge his story on a romance that can survive decades of separation, he needed a more compelling depiction than what these actors can make out of their microchip-thin characterization. As one of the many women to parlay beauty pageant wins into acting careers, Chopra has had more than her share of flower pot roles, but when she gets to do something interesting, she can be very good. This particular film should have given her something interesting, but it doesn’t, and she mostly sinks along with it. She’s livelier than her co-star, who just has no screen presence despite the checklist of “Bollywood hero” things he is given to do: sporty styling, action sequences, nightclub and romantic songs, and an overall “cool bro ca. 2008” general character.

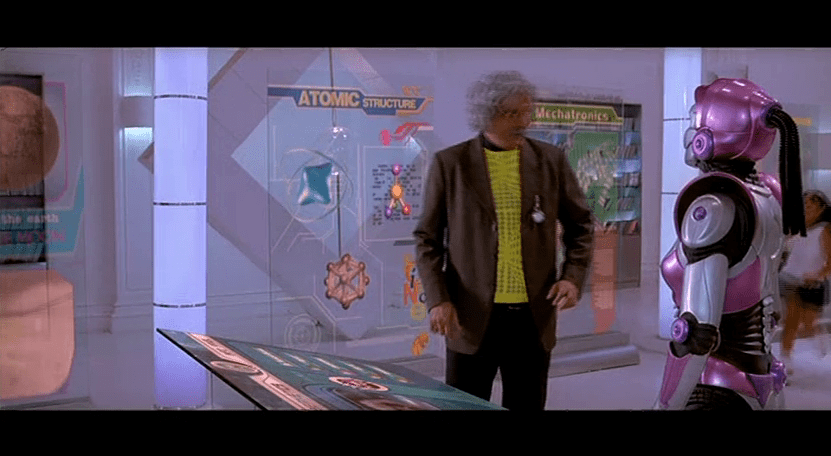

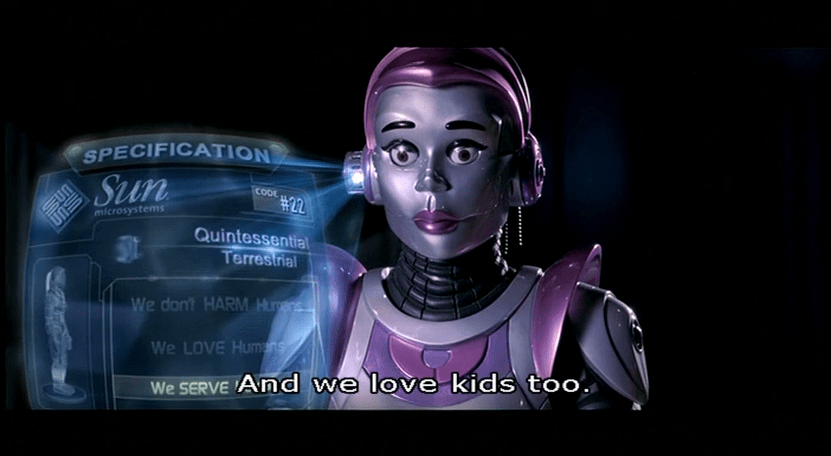

The future does not upgrade any of the other characters. There are a lot of friends and family members around in 2008, but none of them make it into the future. Instead, there’s an android assistant with a purple ponytail called a Quintessential Terrestrial, so of course they call her QT. The jokes set up by this name, Boo, and the younger siblings—plus Sana’s obsession with a pink finger puppet she names Winkydinks—make me wonder if this film was supposed to be for kids. It’s cutesy rather than cute. The Hindi cinema tradition of making films that entire families can see together can mean that children see content that they probably need more context to process, but it can also mean that older audiences are saddled with unnerving treacle. My favorite character in the future is a hologram version of Dr. Ya at a science center named after himself. As a museum professional, I was distracted from the conversation between the time traveler and his hologram by all the exhibits in the background, but the hologram eventually freezes up in the face of Ya’s nonsense.

Since I barely remembered my first viewing of this film, I was waiting for the 2050 portion with optimism. Maybe the future would be really inventive or substantively utopian or full-on dystopian—like magnifications of today’s problems or some horrifying but boldly-examined outcomes of what we think of today as progress. But no, it’s just flying cars and lots of neon. With a run time of over 2 hours 45 minutes, the film is certainly long enough to have put in some world-building. I can’t tell you how happy I would have been to see 15 minutes spent on even secondary references to what Mumbai in 2050 is really like rather than on Sana and Karan’s tepid romance. There’s a brief glimmer of promise when Karan and co. first land in the future at a dilapidated building marked with a sign that says it’s under dispute and entry is banned by Mumbai high court in 2039. “Yes!” I thought. “Of course the rights to land are a hot issue in the maximum city decades into the future! That totally tracks!” But that’s the last we hear of anything like it.

However. Maybe I was just in a mood to be delighted, but I was really engaged by the film’s aesthetics. It’s true that in mainstream Hindi cinema you can have big dance numbers full of unusually attired backup dancers any time you want, but it’s also true that the costume designers had some fun in this one.

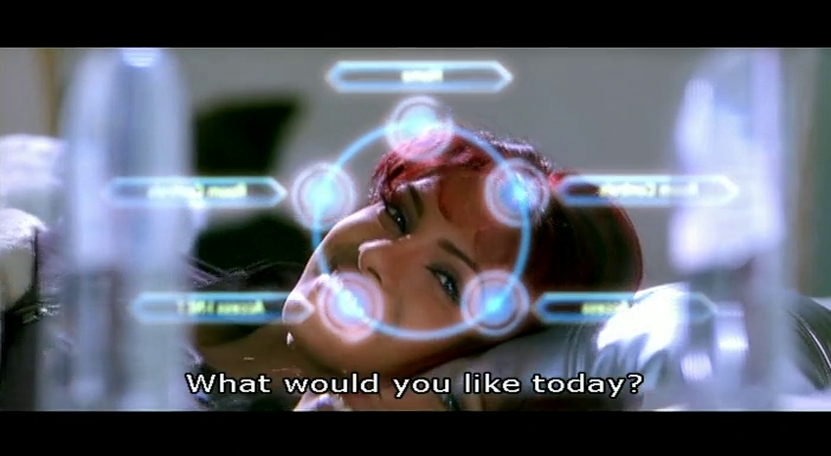

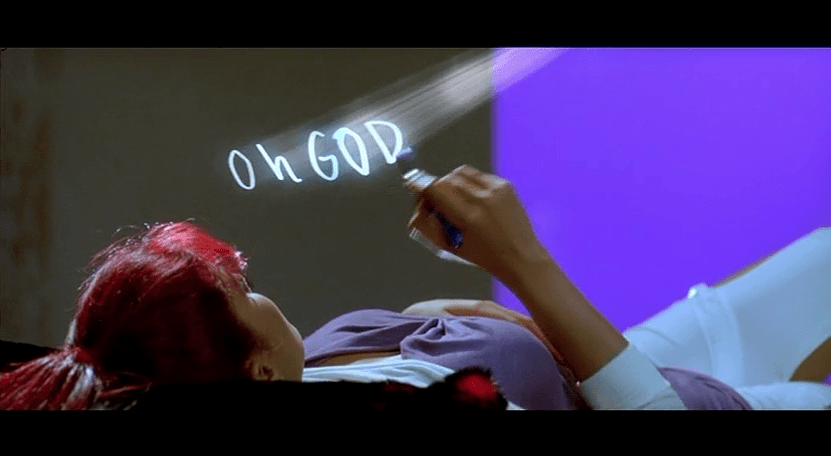

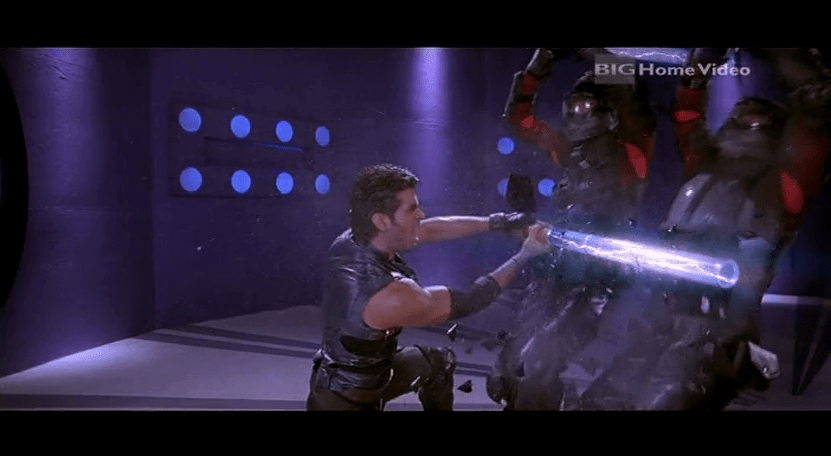

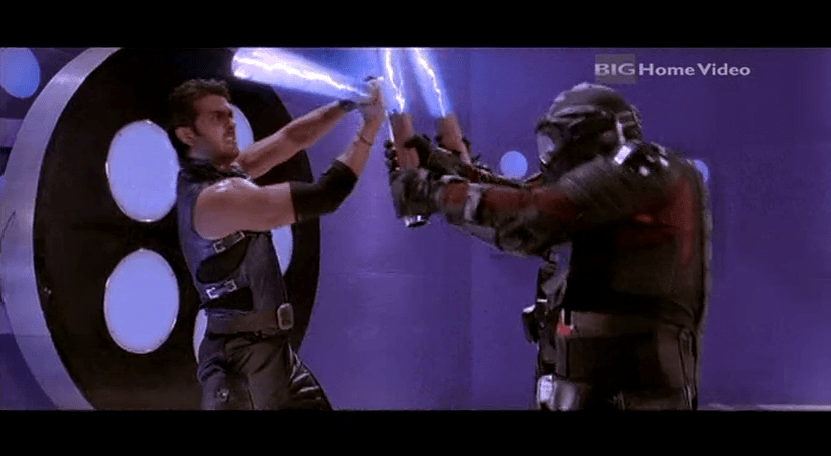

I also liked some of Ziesha’s gadgets, like walls that can change color as easily as our LED bulbs do and a pen that writes with light in the air (both invented by Uncle Ya, his hologram has informed us). Karan gets to fight with an android version of himself with an ersatz lightsaber, which is exactly the kind of detail that reinforced my decision to bring this film to The Cultural Gutter.

Mumbai of 2050 blends some of its iconic architecture in with the new; as a fan of historic preservation, this pleased me. I also think it’s a sign of the filmmakers wanting to do more than was strictly called for; integrating actual buildings into your future design takes more thought than just drawing gleaming buildings from scratch and covering them with neon signs. Similarly, all the extras I saw were wearing something other than standard 2008 gear, and given the crowds at Ziesha’s concerts and other events, that’s saying something. Sometimes costume design in mainstream Hindi films seems to stop at the backup dancers, but not here. I’m not knowledgeable about effects technology, but nothing here looked hokey in a way that “it was 2008” doesn’t solve.

Let’s dig into what else of actual or even potential interest can be found in this film’s version of the future. Sana’s reincarnation in the 2050 part is the only nod to Hinduism I noticed anywhere, implying that the 2050 of 2008’s India is far more secular than the 2050 of 2025’s India (or the US, for that matter). I don’t know how her reincarnation is predicted with such certainty, nor do I know why she is probably in her 20s in 2050, even though if she had reincarnated soon after her death in 2008, that would make her 42, which she decidedly is not, Douglas Adams be damned.

I also don’t think I’ve seen a reincarnation film go much further ahead than the year in which the film was released. All of the examples I can think of, such as those linked above, deal with the past. Moving the film that far forward in time helps disorient the travelers in a pleasing way, but this is another example of bad writing for the characters. Ya seems appreciative of the future, but because of his genius doesn’t seem perplexed by anything; the kids are perhaps too young to realize how much things have changed; and Karan is too much the hero to notice much of anything other than his quest. Similarly, this gap of 42 years could explain why we don’t see Sana’s grieving parents (the action has also moved from Australia to Mumbai, although Sana mentions she was born in Mumbai, so in theory it wouldn’t be surprising if her parents had other connections there and chose to return or at least visit, and that would make a fun opportunity for them to see Karan and be confused by his presence, etc). Their absence also means a lack of that emotional depth, and particularly without it being discussed at all, I missed it. The conversation between the real and hologram versions of Dr. Ya could also be a point of more substance: a discussion of the concept of self, perhaps, of whether future is fixed or in flux, of the societal impact of his inventions. But instead the film plays their exchange merely for goofiness. It could have had both substance and goofiness, but it doesn’t.

The more art I engage with, whatever the medium, the more I appreciate projects in which creators had a vision and really went for it, and I’m less bothered if they missed their mark (or any mark at all) as long as they tried. Love Story 2050 is not quite in this category because I don’t think it tried hard enough in the writing, but at least the visuals were fun. There are aspects that feel unusual and even experimental. A sense of glee bubbles up through some of the future, again mostly visually but also with moments like Ziesha striding about in her pleather and platform boots or playing with her VR Xbox.

Most surprising to me on this rewatch, I kept seeing similarities to the highly regarded 2010 Tamil film Enthiran (Robot), which is beloved by everyone and continually held up as a massive creative success, in addition to its monster box office figures and cult status outside India. I even scribbled in my notes, “Did Love Story 2050 walk so that Enthiran could run?!?”

This notion is all but unthinkable—the scale, tone, star power, effect, and reception of the two films could not be more different—and yet I couldn’t stop wondering about it. I don’t know the production timeframes for the two films, and their plots aren’t significantly similar, but I kept seeing things on screen in Love Story 2050 that reminded me of Enthiran (QT [left] looked familiar, for example, but I hadn’t remembered her the way I did the robot from Enthiran).

Even with its fleeting fun details, there is nothing in the world of 2050 that is truly integral to the story—or even has any influence on it. Sana could be an emotionally closed-off pop star in 2008. She could have been kidnapped to a foreign country or even a remote corner of India, and the challenges Karan and Ya faced in finding and retrieving her would be the same. There’s not even any real emotional payoff for the vindication of Uncle Ya’s invention; it’s not like the film got us to care about his triumph over mean-spirited philistines who couldn’t see the glory of his vision. He’s just a well-meaning kook who has some good ideas. 2050 does nothing for this film except make its title sound way more exciting than it really is.

On the bright side, maybe the un-noteworthy future means the whole world will sort its shit out by then and we can just enjoy our 3D digital ads and floating concert stages in peace.

* The plot of the Telugu film Aditya 369 (1991) swings between 1526 and 2504, and Fun2shh… (2003) bloops its protagonists back to the 10th century.

~~~

Beth Watkins has written this entire piece with her light pen, but her future shoes are way more practical.

Categories: Screen

QT is terrifying.

LikeLike