This week’s Guest Star is friend of the Gutter Kate Laity!

~~~

Men love ‘crazy’ women.* In fiction, anyway: they love the ‘truth’ of revealing what’s inside those other creatures men are so sure are completely different from them—another species! Women are from Venus, men are from Uranus or however that pop psychology goes. They love the certainty that women are such mysteries, unknowable, alien. Otherwise they’d have to face that fact that if they were systematically treated as a despised underclass they might act the same way (see also every racist/xenophobic/homophobic trope of irrational monstrosity).

Yet sometimes the crazy lady even becomes an icon.

The Papin Sisters were once as well known in France as the Manson Family continues to be in the US. Sisters Christine and Léa Papin were live-in domestics for the Lancelin family. Madame Leonie Lancelin, bedevilled by her own mental health issues, took out her anger on the dependent sisters for years in both verbal and physical cruelty. On 2 February 1933 everything exploded, resulting in not only Leonie’s death, but that of her daughter Genevieve. The two were not only killed, but mutilated with vehemence, their eyes gouged out and their thighs and buttocks carved up by the sisters. France was shocked that two young women could be so brutal. The case highlighted the poor treatment of the working class and inspired not only the Surrealists, but other 20th century French intellectuals like Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sarte and Jaques Lacan, as well as numerous fictional works from Genet’s The Maids to possibly Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite, but definitely Claude Chabrol’s La Cérémonie.

In France about ten years earlier, Andre Breton decided Dada—the art wave responding to World War I with a flood of deliberately staged nonsense—wasn’t deranged enough and announced the Surrealist movement in his 1924 manifesto. But there were competing Surrealist manifestos: Yvan Goll wrote one, too, and got it out two weeks before Breton’s. Both claimed the mantle snatched from the shoulders of the poet Guillaume Apollonaire, who coined the term ‘surreal’ in program notes for a ballet by Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie in 1917, a year before his death. [Sorry, but name dropping is inevitable even in the briefest potted history of the movement and if you don’t know these people you would benefit from the acquaintance].

After some wrangling, Goll and Breton battled over the right to claim leadership in a fight at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées, which I always imagine looking like a fight between Keaton and Chaplin with jazzy ragtime piano playing. Breton won and became even more insufferable (just the facts, ma’am). His version of Surrealism triumphed. He kept tinkering with it, but at heart it was about circumventing reason using automatism and dreams, being non-conformist—except when it came to conforming to Breton’s rules. You could be expelled for not conforming to them. Fisticuffs optional. In fact, fisticuffs were rare. Animosity was generally more like a mean girls freeze-out.

Unsurprisingly, Breton mostly recruited men to join his movement. There were women, but Breton rarely saw them as anything but muses—unless they frightened him like Leonor Fini. His novel, or rather roman à clef, Nadja dealt with a woman whose strange vision of the world inspires Breton until he understands what caused her mental breakdown AND THEN he breaks up with her. Her job as muse was done. He ends the novel, ‘Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or will not be at all’, but Convulsive living is not comfortable as any seizure-prone soul will confirm. Léona Camille Ghislaine Delacourt, his inspiration, died in an asylum at age 35.

One woman who became associated with the Surrealists but had ‘no time to be anyone’s muse’ was Leonora Carrington. She was one of the few women Breton grudgingly admired, even including her as one of only two women in his Anthologie de l’humour noir. I suspect it was her wit that got past his prejudices. As we know, funny women do tend to terrify men. Carrington, however, experienced a mental breakdown first hand and did not romanticise it the way the men did with their image of the femme-enfant. She survived it, just as she survived the misogyny of her family’s social striving (read her short story, “The Debutante”), the sexism of the Surrealists, WWII in France and Spain (the latter where she was incarcerated in a mental hospital and given chemical shock treatment, as detailed in her memoir Down Below), and exile first in New York and then in Mexico City. If you want true surrealism, Carrington is your icon (see also her best pal, Remedios Varo). She embodied the glories of surrealism for most of her 92 years.

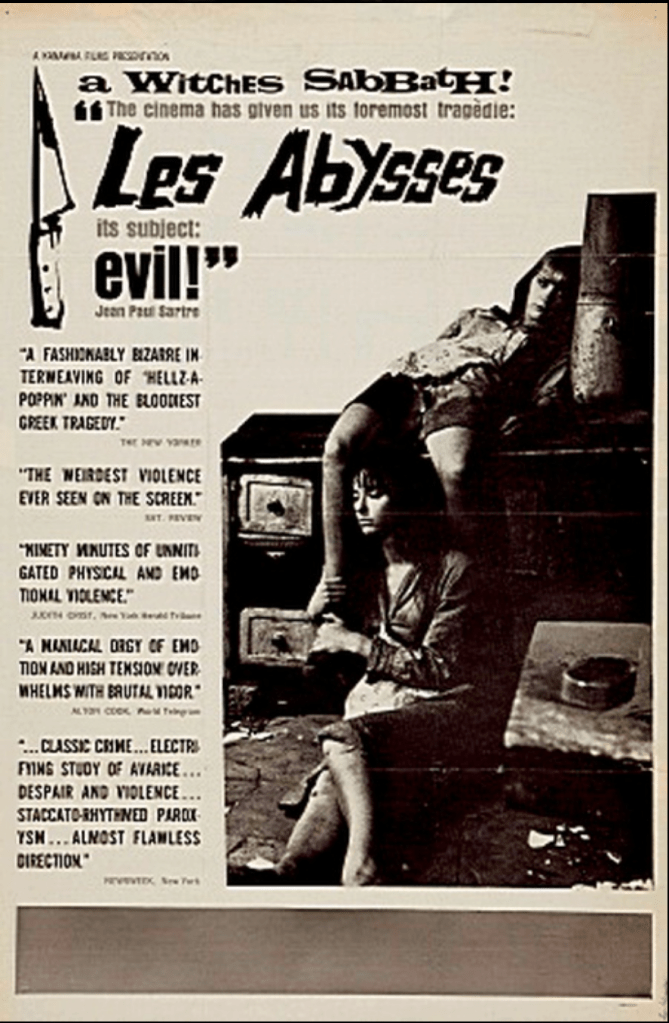

All of this is a long meandering prologue to talking about Les Abysses, Greek-Ethiopian director Nikos Papatakis’ 1963 film inspired by the Papin sisters’ murders.

One might expect that a filmmaker would make much of the significance of eyes. Surrealists were all about the eyes. He did not. A director who established himself in Paris by 1939 and ran La Rose Rouge might be expected to be steeped in the surrealist haze around the sisters’ notorious story. Papatakis certainly enjoyed a succès de scandale when the Cannes Film Festival refused to show his film (doubtless as he predicted). Starring the sisters Francine and Colette Bergé, the film begins with violence and ‘madness’ and ends with an admonishment to the audience about class. While Les Abysses partakes of the surrealist vibe the film never quite surrenders to it.

The disjoined opening scenes are well matched by the disorienting music by Pierre Barbaud, the Algerian-born composer best known for his soundtracks to Last Year at Marienbad and Hiroshima Mon Amour. Marie-Louise (Colette Bergé) screams on the stairs, then stabs at the wall with a knife while her sister looks on, then tears up some papers by a sofa, then the two embrace in the night on flagstones, laughing. Afterward the sisters climb wooden steps to a roof where they gaze upon the world around them while Marie-Louise stomps her foot. We cut to Michèle (Francine Bergé) hiding amongst some wine barrels, then cut to a spigot pouring out wine (millions of francs worth we’re told later). Marie-Louise comes looking for her, and they run out again.

The title then appears superimposed on an image of the actual Papin sisters like a collage poorly cut from tabloids pasted on a blank page. The credits continue, only to be briefly interrupted by a black screen, then continue over footage of Michèle stabbing at something with a fancy hat pin. This weapon emphasises the gendered femininity of the crimes. An object like so many emblematic of ‘female mystery’ yet recognised as potentially dangerous. Thus looms, spindles and spinning wheels were seen as the accoutrements of witchcraft simply because of the association with the domestic sphere and male ignorance of how they work. What is she building in there? Women making things could fill men with awe, but also terror. After all, the ultimate creation of other humans even with all our science retains a sense of magic. And screaming. Nice!

The power to create is inextricable from the power to destroy: Kali and Durga exchange knowing glances. We could see a reflection of this in Les Abysses as Marie-Louise stares into a broken mirror. The ensuing dialogue with her sister reveals her desire to pursue legal aide to address their unfair situation, but Michèle seems unwilling to compromise. Close ups, as she continues to ‘decorate’ the wooden chair back with stab after stab, reveal Michèle’s fixed attention, in which we recognise the deranged woman. Marie-Louise at first smiles indulgently, as if to convey if not approval then a shared pleasure in destruction of the nice things they are denied. She tries to soothe her sister, gently taking the hat pin and putting it away in her pocket. Michèle uses their embrace to steal it back and continue her work: single-minded concentration in contrast to the constant multi-tasking that caring, nurturing women are expected to maintain–Mama is never too busy; the maids are always ready to serve.

The two are decidedly over the top from the start—literally as they perch on the roof of the farmhouse. We understand this is not the beginning but the middle of a crisis, we’re just not sure what. Nevertheless, the crazy women trope is so recognisable it needs little explanation. The disconnected images destabilise context, but for an audience at the time the image of the Papin sisters would be instantly recognisable: ‘Oh, THE famous murderers!’ Context provided; for audiences now, the Papins might not be recognisable but the crazy woman trope is writ in stone.

I am truly shocked that Papatakis didn’t make more of the eyes; a truly surrealist filmmaker would surely do so and yet it seems inevitably the focus is always on the suggestion of incest and hints of lesbianism so familiar to anyone who’s aware of the ‘male gaze’ of the camera. Despite oodles of adaptations and ‘inspirations’ from the Papin’s story even Genet did not seem to grasp their seeing as opposed to being seen (though what I wouldn’t give for a time machine to slip me into the audience of Cate Blanchett and Isabelle Hupert’s turn in The Maids on stage).

If we saw through the sisters’ eyes, what a different film this would be. If we saw the work they put in making those linens spotless, burnishing the wooden furniture to a Happy Home Paradise glow, the hours scrubbing the whitewashed walls, the endless creation of crêpes, daily gathering of eggs—if we saw through their eyes the drudgery as well as the disdain from Madame and the hot and cold sympathy of Elisabeth who dithers between affection for Michèle and the brutal husband she’s abandoned temporarily. The sisters kill the women—no, they murder and brutalise the women—because of a sense of betrayal. They expect no kindness from M. Lapeyre. He is a man.

Les Abysses ends with title cards recounting the Papin case and the fact that even the court sternly asked, ‘Who is truly guilty here?’ yet, of course, the judge sentenced the women anyway. Christine did not survive incarceration and hospitalisation. Léa survived to return to work as a maid. While the French intellectuals questioned the role of class in what happened, it’s the spectacle of their crime that continues to draw attention, as Guy Debord would impatiently affirm. And gender? Oh, don’t we know that problem has been solved? We are post-feminists! All evidence to the contrary, of course.

While men love their crazy women in films, safely contained, what about the rest of us? I suppose we should deplore them, but they are often so satisfying: these women get to do all the things we think about but know (in most cases) are not worth doing. If we can restrain ourselves, that is. We are all too aware of the costs when we are in our ‘right’ minds. In our current climate of gender panic, the stakes for deviance from stereotypes of gender binaries are deadly.

So, I love every stab of the hat pin, every smashed piece of crockery, the shouting, the yelling, the slapping, pouring out the bourgeois wine, flinging the clean linen on the dirty floor and upending every bucket and soup tureen. I’m amazed, too, at the effortless crêpe making! I even envy them wearing the same dirty clothes through the entire film, so they don’t have to even make decisions about what to wear (decision fatigue is real). I feel like making a supercut of the best scenes of the film to Hole’s Violet.

There are so few outlets for women’s rage. You bottle it up until it explodes in a bloody murder scene, or you watch a film and try to dispel it vicariously. Anger is an energy, but it takes a lot of work to make that energy productive rather than destructive. It’s exhausting. And I am a relatively privileged cis white woman; while the underpinnings of my life have been kicked out from under me recently, I have a network and resources to draw on (whenever I get around to setting aside all the rage to do something practical about it).

Those who don’t—or those who labour under far more categories of prejudice—don’t have the same luxury to wallow in despair or wring their hands. There’s work to be done. Yet we need rest; we need to recover. And we need to dream. Occasionally, we need nightmares to remind ourselves that our anger is powerful. Look around. See where it can be employed usefully. Some people need to be scared of us.

~~~~

K. A. Laity is an ex-professor who has watched the systematic destruction of the liberal arts in the West and is not amused by the Debordian spectacle. Yet she endeavours to Live Gold as Latitude Zero would teach us.

*Mental illness is real; I am deliberately using ‘crazy’ here to refer to fictional works, which may at times overlap with genuine diagnoses. I am interested in the ways that anything inconvenient women and non-binary people do is called ‘crazy’.

Categories: Guest Star, Screen